Tommy Kuni Thompson served as the headman of Wyam (an Ichiskiin Sinwit word that translates as "echo of falling water" in English), also called Celilo Village, and was the salmon chief at Celilo Falls during the tumultuous final decades of the traditional Indigenous fishery there. He was a lifelong advocate not only for his community, but also for mid-Columbia Indian treaty fishing rights and the way of life and the natural resources they protected. In particular, he and his family stood firm against construction of The Dalles Dam and challenged the discourse of “progress” that justified such development projects at the expense of Native peoples and the environment.

Thompson’s date of birth was not officially recorded, and some accounts place it as far back as 1855, the same year his uncle Stocketly signed the Treaty of Middle Oregon on behalf of the Wyampam, or Wyams. Villagers often threw large birthday parties for Chief Thompson during the Christmas season, and at the 1955 celebration he reportedly turned 102. By his own reckoning, he marked his eightieth birthday in 1944, which would have made him roughly ninety-five at the time of his death in 1959.

A commanding presence even in old age, Chief Thompson was described by one local resident as “a cross between Jim Thorpe and the Pope. Tall, handsome, and athletic, a famed swimmer and boatman in his youth, he was married to as many as seven women at one time.” Census records suggest a more modest tally, with two wives (Minnie and Ellen) recorded at different times before his final marriage, to Flora Cushinway in 1943.

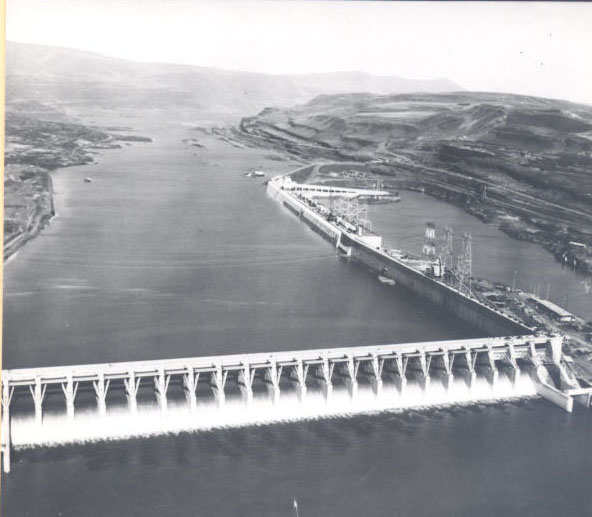

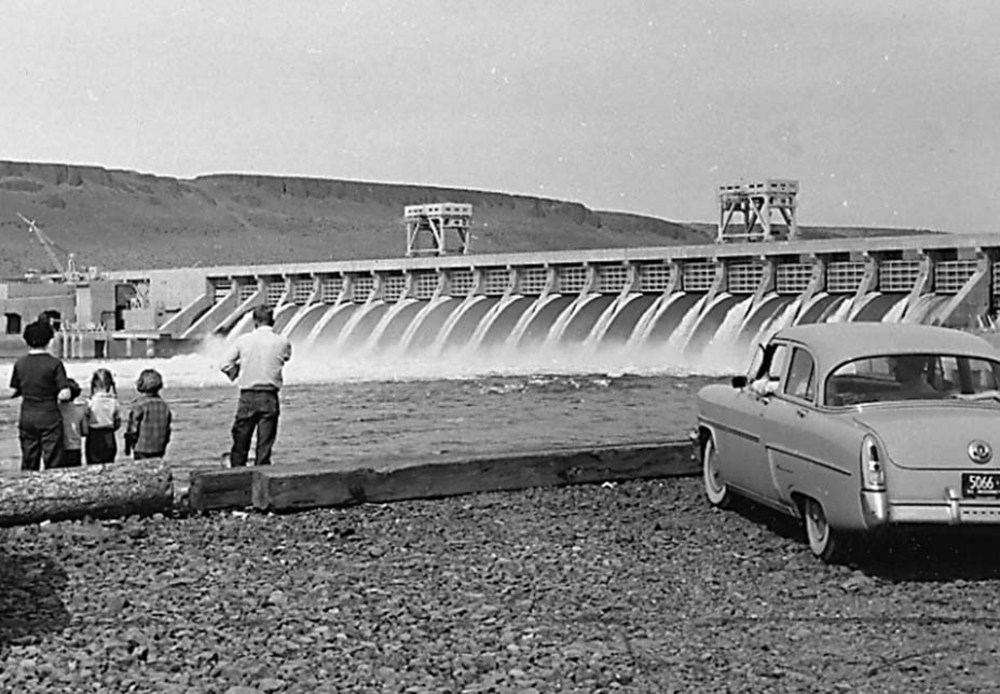

Regardless of his exact age, Chief Thompson lived a long life and witnessed many changes along the mid-Columbia River, culminating in the traumatic flooding of Celilo Falls by the backwaters of The Dalles Dam in March 1957. By that time, Celilo Village had already been moved three times to accommodate a railroad, a canal, and a highway. Each of those development projects had driven a wedge between the Wyams and the river where they made their living, but Chief Thompson and his people clung stubbornly to their ancestral home. “My father told me, before he died, that I must always take care of these usual and accustomed fishing rocks,” he said of the ancient fishery that had sustained his community for more than ten thousand years. “I have always done that; I have always remained there and never moved to any reservation. I respected my old people and the place where they lived and the food that was given to the Indian people.”

Thompson assumed the role of salmon chief (láwat, or “belly”) at Celilo in about 1900, during a period of increasing competition and growing conflict over treaty-reserved fishing rights. Traditionally, the salmon chief presided over the annual first-salmon ceremony of the Waashat religion, set the fishing season, and enforced spiritual rules against fishing at night, on Sundays, and after drowning deaths in the turbulent waters of the Columbia. Thompson spent the last fifty years of his life fighting to uphold his authority and protect the falls and the village from destruction at the hands of white settler society.

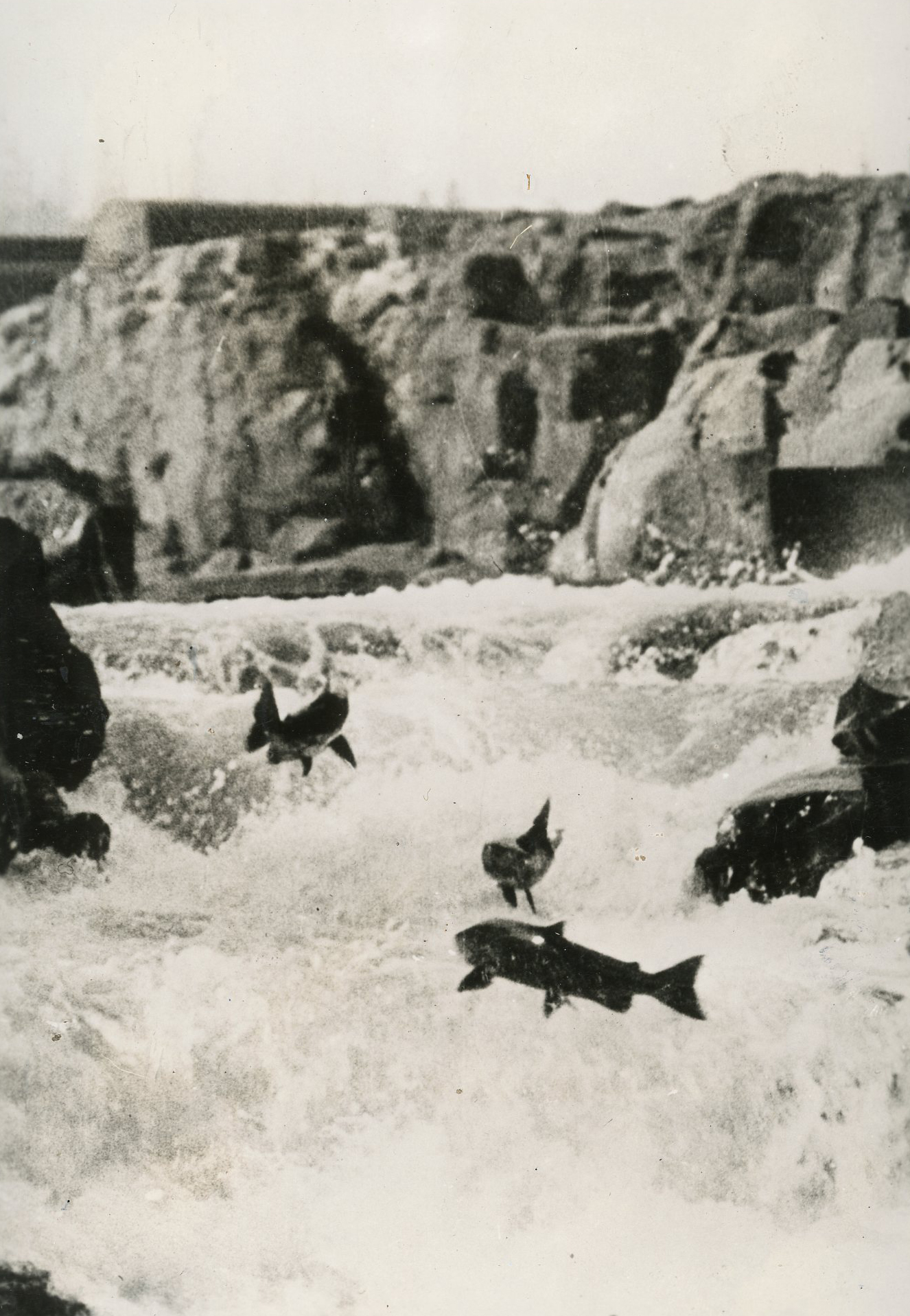

When Thompson was young, perhaps three to five dozen men regularly netted salmon on the islands across from Wyam. Salmon, or nusux, is one of the five sacred foods of the Waashat faith and provided the main source of protein for Plateau peoples. Starting in the 1870s, however, it became a lucrative commodity that non-Indian fishers and packers exploited for a global market. By the mid-1930s, as whites usurped or destroyed other Native fisheries along the Columbia, two hundred to three hundred people crowded the rocks at Celilo each season. While some possessed aboriginal rights at Celilo through blood or marriage, others were non-Indian intruders or nontreaty Indians attracted by the commercial buyers at the falls. Many were “comers” from the Yakama, Warm Springs, Umatilla, and Nez Perce reservations who claimed tribal rights to fish at Celilo under their 1855 treaties with the U.S. government. Thompson worked with federal officials and tribal representatives to manage the fishery through the Celilo Fish Committee, established in 1935, but he never warmed to an arrangement that seemed to both undermine his authority and fail to rein in nonresidents who refused to obey the rules.

Despite these tensions, Thompson urged unity among tribal fishers when the federal government announced its intention to build a dam nine miles downstream from Celilo Falls. As he explained to a mass meeting of fishers from different tribes in 1945, “I believe we might say that if this plan of the white man is carried out we will all be made the subjects of charity. And I want you all to consider this question and the right steps to take to cooperate by joining together as a solid force.”

To Thompson’s dismay, the Army Corps of Engineers effectively used divide-and-conquer tactics over the next decade to compel reservation-based councils to sign monetary settlements compensating tribal members for the loss of the fishery. Although he had connections to the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Thompson refused to enroll in any of the recognized tribes or to “signature away” his rights by accepting a share of the settlement. He would not even look at The Dalles Dam when it was completed in 1957.

Chief Thompson died in 1959 in a nursing home downriver from Celilo. His wife Flora Cushinway and his son Henry (from his first marriage) continued to represent the people of Celilo Village in the ongoing fight for the treaty rights of mid-Columbia Indians.

-

![]()

Chief Tommy Kuni Thompson.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi23891

-

![]()

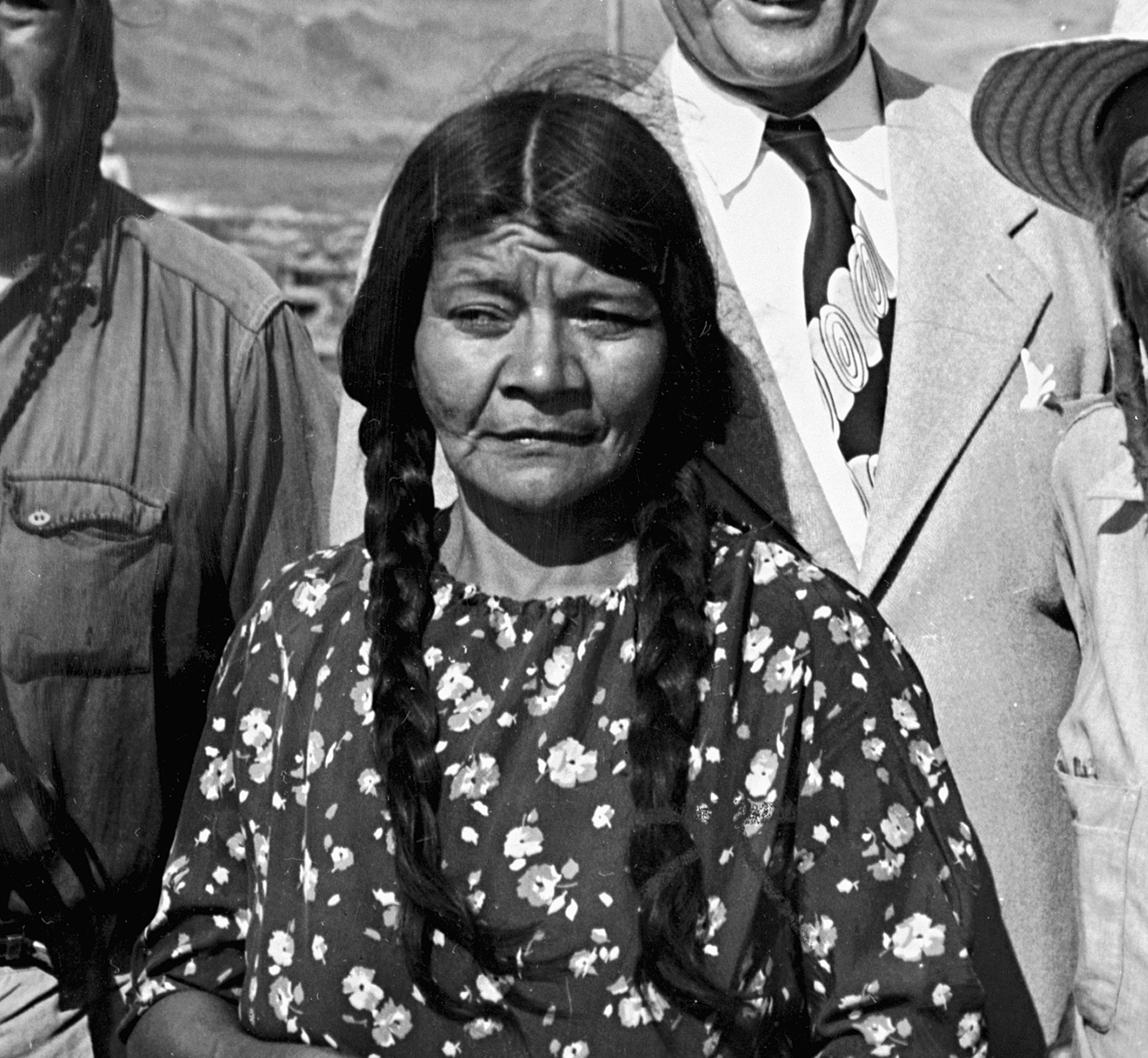

Chief Tommy Kuni Thompson and Flora Cushinway Thompson, Celilo Village, 1955.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 1284 -

![Members of the Rock Creek and Celilo bands met in Condon to form an alliance in opposition to outside interference at Celilo Falls.]()

Willie John Culpus, Henry Thompson, Tommy Thompson, and John Whiz, Condon, 1948.

Members of the Rock Creek and Celilo bands met in Condon to form an alliance in opposition to outside interference at Celilo Falls. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, CN015009

-

![]()

Flora Cushinway and Chief Tommy Kuni Thompson, 1955.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Org. Lot 1284 -

![Multnomah County Library event celebrating the release of McKeown's release of her book "Linda's Indian Home."]()

Chief Tommy Thompson, Martha Ferguson McKeown, Linda Meanus, Catherine Cushinway, and Ida Thompson, 1956.

Multnomah County Library event celebrating the release of McKeown's release of her book "Linda's Indian Home." -

![]()

Chief Tommy Thompson relocating to new Celilo Village, c. 1956.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi73669

Related Entries

-

Celilo Falls

Celilo Falls (also known as Horseshoe Falls) was located on the mid-Col…

-

![Celilo Fish Committee (1935 - 1957)]()

Celilo Fish Committee (1935 - 1957)

Members of Umatilla, Yakama, and Warm Springs tribes joined unenrolled …

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Flora Cushinway Thompson (1898–1978)]()

Flora Cushinway Thompson (1898–1978)

Flora Cushinway Thompson (enrolled Warm Springs) was a spiritual and co…

-

![Martha Ferguson McKeown (1903-1974)]()

Martha Ferguson McKeown (1903-1974)

Author, historian, teacher, Martha McKeown, a third-generation Oregonia…

-

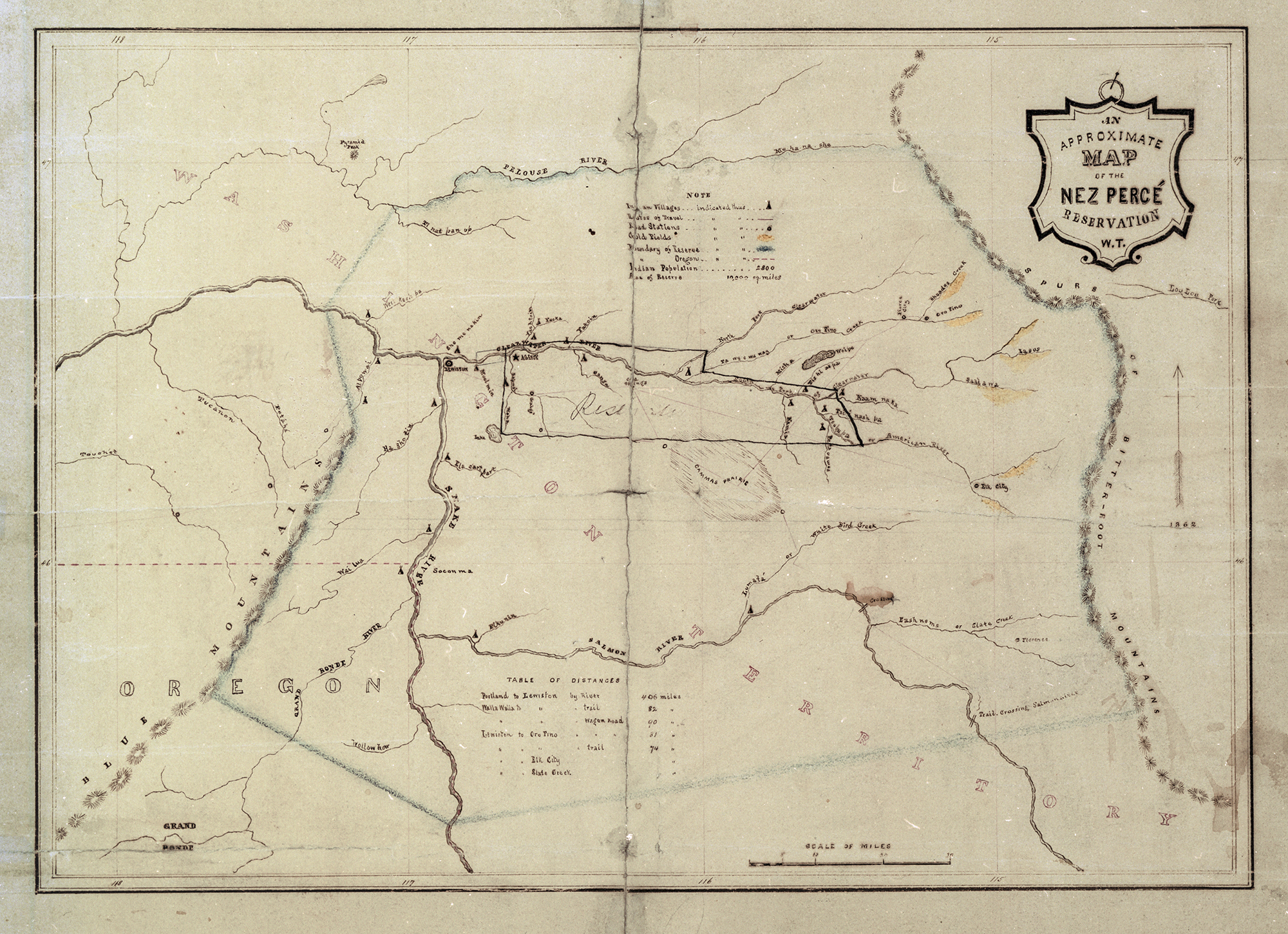

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

-

![Salmon]()

Salmon

The word “salmon” originally referred to Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar),…

-

![The Dalles Dam]()

The Dalles Dam

The United States Army Corps of Engineers constructed The Dalles Dam be…

-

![U.S. Army Corps of Engineers]()

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, a hybrid military and civilian federa…

-

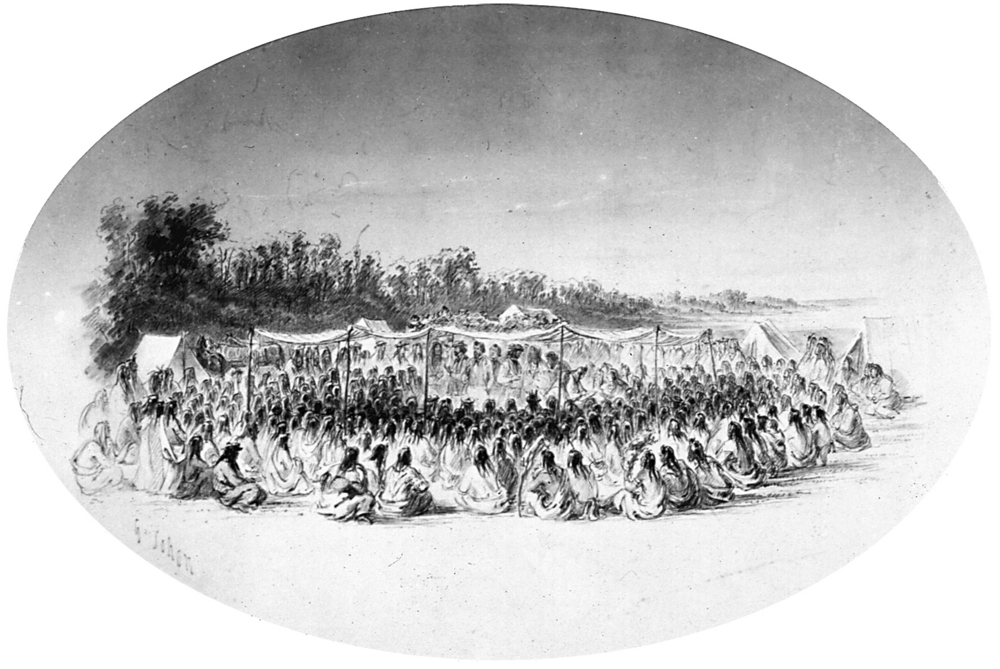

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Barber, Katrine. Death of Celilo. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Barber, Katrine. In Defense of Wyam: Native-White Alliances and the Struggle for Celilo Village. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018.

Dupris, Joseph C., Kathleen S. Hill, and William H. Rodgers, Jr. The Si'lailo Way: Indians, Salmon and Law on the Columbia River. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2006.

Fisher, Andrew H. Shadow Tribe: The Making of Columbia River Indian Identity. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010.

Rohrbacher, George. "Ken Kesey Meets Lewis and Clark." Commonplace, Vol. 6, No. 2.