Pittock Mansion was built high above the city on Imperial Heights in the West Hills of Portland. Built by Henry and Georgiana Pittock between 1909 and 1914, the mansion's bright, red-tiled roof can be seen from many points in the metropolitan area, and is, according to Classic Houses of Portland, “the most beloved…of all the great houses of Portland….It typifies the success of the nineteenth-century American entrepreneurial spirit.”

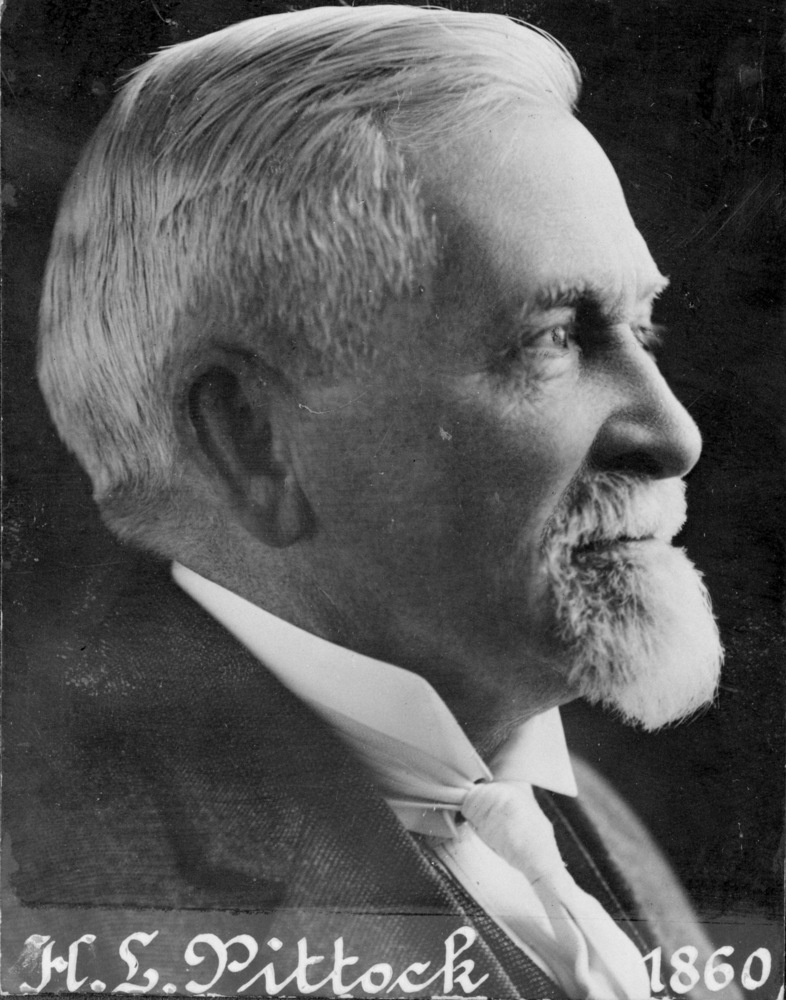

The Pittocks were among Portland's most influential, respected, and wealthiest citizens at the turn of the twentieth century. Henry Pittock was the owner of the Oregonian, and Georgiana Burton Pittock was engaged in many community projects and was a founder of the Portland Rose Festival. In 1909, when he was seventy-three years old and she was sixty-four, they hired Oregon-born architect Edward T. Foulkes from San Francisco to design a 16,000-square-foot home on the 46-acre wooded estate, a thousand feet above sea level. The Pittocks moved into their new home in 1914, only a few years before both died, she in 1918 and he a year later.

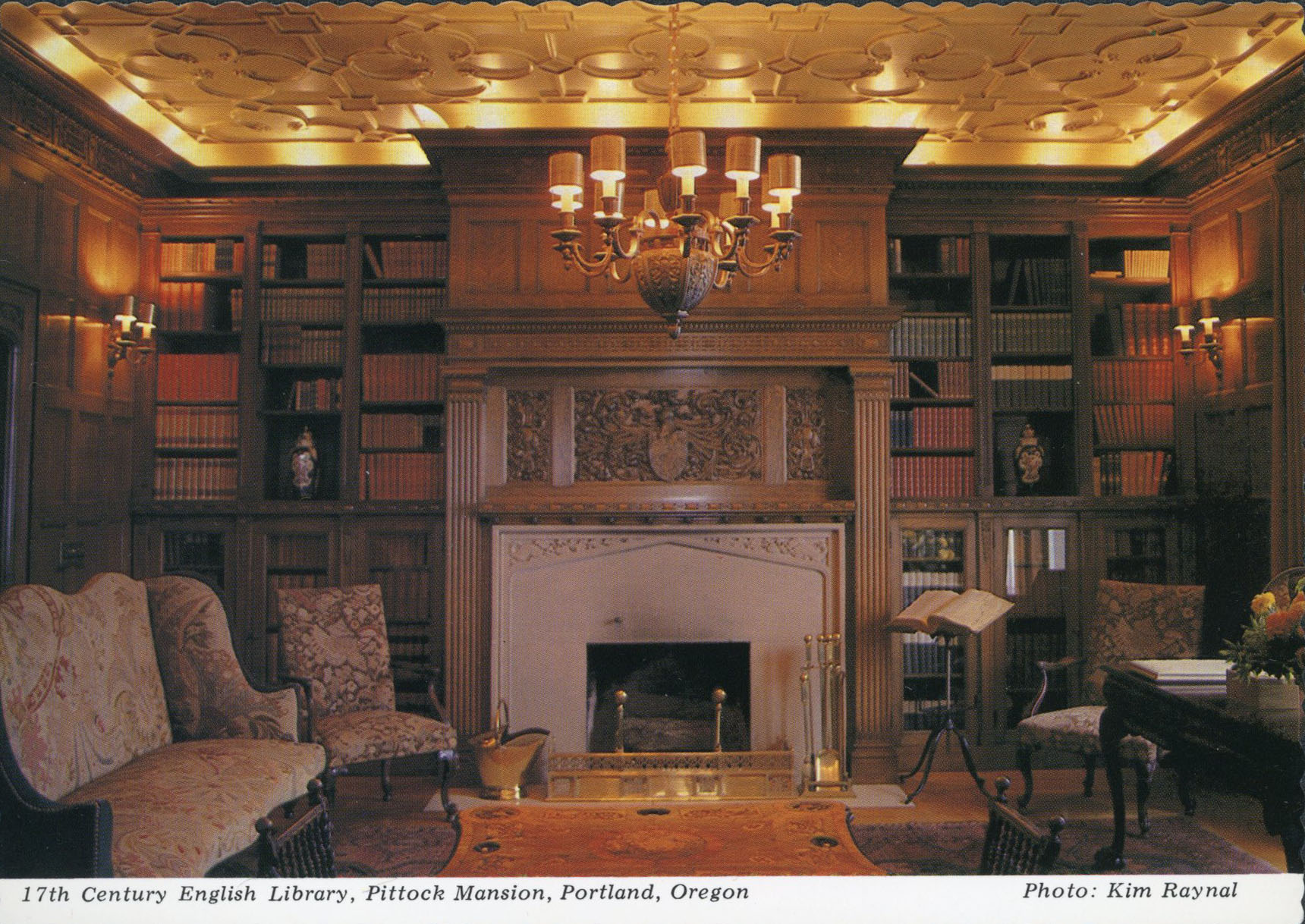

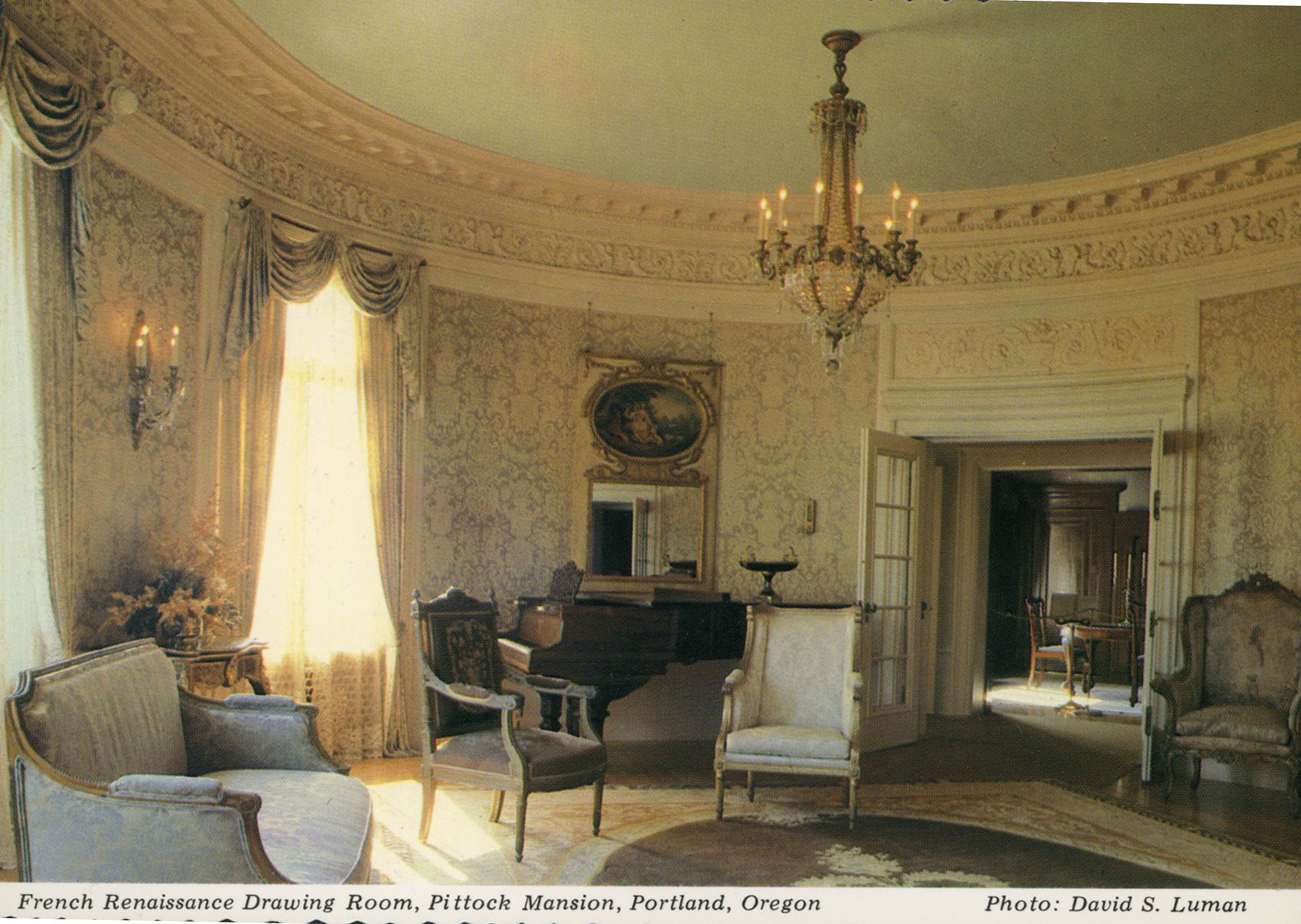

The exterior of the mansion is French Renaissance, but the interior is a collection of styles, from the oak-paneled and carved Jacobethan library with an elaborate plastered ceiling to the French-style oval drawing room with oak parquet-bordered floor, friezes, and capped cornice at the ceiling. Adjoining is a round Turkish smoking room with a painted ceiling and Tiffany glazes, created by artist Harry Wentz, and a formal Edwardian dining room with rich mahogany-paneled built-in cabinets. A mirror on the west wall is positioned to show a reflection of Mount Hood, giving everyone sitting around the table a view of the mountain.

The most prominent interior feature is the central stairwell, which occupies one-third of the mansion space and connects three stories. The floors are marble, and the railing is made of eucalyptus. The bronze grillwork required 200 different castings because of its twists and turns, and the bronze light fixture is equipped with electric lights and gas jets for emergencies.

Despite its size, the mansion was designed as a family dwelling. The semi-circular gallery on the second floor leads to three bedroom suites of three rooms each. They are arranged as sitting rooms with a fireplace, dressing rooms, bedrooms and bath, with sleeping porches at each wing for healthy sleeping year-round. All fixtures and appointments are in the Edwardian style. Henry Pittock’s turreted bathroom, which has a panoramic view of five distant peaks of the Cascade Mountain Range, has a hydraulics masterpiece shower—a human carwash with horizontal needle sprays to reach all parts of the body, including a “liver" spray and a “toe" tester.

The third floor houses three servants’ rooms, a bath, Henry Pittock’s office, and the largest room in the house, the children’s play room, big enough for riding tricycles. The underground level has an oval billiard room with adjoining round card rooms, a walk-in vault, a wine cellar, a laundry room, and storage areas. Carefully placed windows allow for maximum daylight.

Technical innovations include an elevator, indirect lighting, intercoms, a walk-in refrigerator, central heating, a dumbwaiter, and a central vacuuming unit. The estate has a four-story gatekeeper’s lodge and a three-car garage with a chauffeur’s apartment above. Renaissance-style gardens include a terraced flower garden, a tennis court, and connections to Portland parks trails.

Family members lived in the mansion until 1958, the last being grandson Peter Gantenbein, who was born there. The house then stood empty for six years, a victim of heavy damage by squatters and the 1962 Columbus Day storm, which blew off a third of the roof tiles. The City of Portland, realizing that the mansion was an evocative architectural treasure, acquired the dilapidated house in 1964 for $225,000 and saved 46 acres of the original estate from being developed as a subdivision. Some of the craftspeople who had worked on the original house, such as Fred Baker who had designed the lighting and Bruno Dombrowski who had laid the wood floors, came out of retirement and helped with the fifteen-month-long restoration.

The mansion is now a public museum, visited by 60,000 to 70,000 people a year—18,000 alone in December 2009. The estate has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1974.

-

![]()

Pittock Mansion.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 1828a

-

![]()

Construction of the Pittock Mansion, c.1910.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 86598, photo file 1828a

-

![]()

Pittock Mansion, 1973.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 36293, photo file 1828a

-

![]()

Aerial of Imperial Heights, Portland, with Pittock Mansion.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Ackroyd photography, photo file 1828a

-

![]()

Gatekeepers lodge, Pittock Mansion, 1973.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., R132, photo file 1828a

-

![]()

Staircase, Pittock Mansion.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 1828a

-

![]()

Library, Pittock Mansion.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 1828a

-

![]()

Drawing room, Pittock Mansion.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 1828a

Related Entries

-

![Georgiana Burton Pittock (1845–1918)]()

Georgiana Burton Pittock (1845–1918)

Georgiana Burton Pittock was the founder of the Portland Rose Society a…

-

![Henry Lewis Pittock (1836-1919)]()

Henry Lewis Pittock (1836-1919)

Henry Lewis Pittock, longtime publisher of the Portland Oregonian, was …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bookwalter, Jack. “Portland’s Pittock Mansion.” Northwest Renovation Magazine (April/May 2006), pp. 6-9.

Hawkins, William J., III, and William F. Willingham. Classic Houses of Portland, Oregon, 1850-1950. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, Inc., 1999.

Pittock Mansion. http://pittockmansion.org.

Wilson, Janet L. The Queen of Portland's Roses: The Life of Georgiana Burton Pittock. Lake Oswego, Ore: Panoply Press, Inc., 2006.