Pine nuts, the edible seeds of Pinus sp. trees, are a key food source for many species, including bears, deer, birds, rodents, and even porcupines. Humans, too, have had a long relationship with pine nuts, and several species of pine are important to Indigenous peoples who have lived in present-day Oregon for millennia.

All pine trees produce seeds, though not all are large enough to be substantial and easily accessible sources of calories. The most commonly consumed seeds include the nuts of whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis), sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana), and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa). Written records indicate that Chetco, Coos, Galice/Applegate, Lower Umpqua, Nez Perce, Northern Paiute, Siuslaw, Takelma, Tolowa, Umatilla, and Warm Springs people all consumed pine nuts, and archaeological evidence and anthropological interviews may further expand upon their importance across Oregon. Pine nuts were so significant for many tribal groups—including Coos, Lower Umpqua, Umatilla, and Warm Springs—that the word for pine tree in those languages is the same as or similar to the word for pine nut.

Whitebark pine is a favorite source of pine nuts among many Indigenous groups who live near the Cascade Range and the Wallowa Mountains, where the trees grow in high timbered areas. Ethnographic accounts and oral histories often highlight whitebark pine nuts as the preferred species that people traditionally gathered for food. Although specific harvesting and preparation practices vary by community, most groups harvested whitebark seeds and other types of pine nuts in late summer to early fall. They collected seeds and cones by knocking or climbing trees, using poles or hooks, and cutting down branches. In some groups, children or teenagers were encouraged to climb the trees to gather cones while adults harvested huckleberries and other forest foodstuffs on the ground.

To release pine nuts, pinecones must be cracked, roasted, or steamed. As the cones are heated, the scales open, making it easy to extract the seeds. Roasting or steaming pits were constructed by excavating a pit or by repurposing camas or other in-ground baking pits. Rocks often were heated nearby and added to the bottom of the pit, followed by layers of pinecones and needles and a final layer of soil. Left overnight, the seeds were released and could then be eaten or sun-dried and stored for winter. Some people recounted the practice of adding cones to existing fires or steaming them with foods such as camas or wild onion prepared in steaming pits. Once roasted, seeds could be pounded into flour or mixed with fat, fruit, or dried berries.

Sugar pine nuts were staple foods for many Indigenous groups in southern Oregon, including Galice, Chetco, and Tolowa people. Large quantities of either green or brown cones were roasted to burn the pitch and release the seeds, which could then be pounded or parched over a fire and added to soup or bread. To ensure the longevity and productivity of sugar pines, groves of the trees were carefully managed by pruning branches, weeding, and using cultural fire to keep the forest floor clear of undergrowth and prevent large fires.

Ponderosa pine seeds also were widely available. Nimiipuu (Nez Perce), for example, harvested the cones during late summer through autumn while they were still green. Cones were placed in a fire to open the scales, and the seeds (lá·qa) were shaken out and roasted, parched, or boiled. Sometimes the seeds were crushed and mixed with fruit or pounded into flour. Western white pine (Pinus monticola) and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) seeds were also eaten, but white pine trees do not produce cones and seeds abundantly until age seventy and lodgepole pine seeds are much smaller and require more effort.

Coyote is a common figure in myths and folklore throughout the more arid parts of the intermountain west, and many stories feature him as a creator, cultural hero, or trickster. Several stories about pine nuts offer place-names or recipes. In one Nimiipuu tale, for example, pine nuts were mixed with water and boiled. Northern Paiute tales highlight the role of Coyote in bringing pine nuts to the land, often through stealing, belching, or vomiting.

Pine nuts were also a valued trade item and used in personal adornment. In communities in present-day northern coastal California, beads were created from seeds of grey pine trees (Pinus sabiniana). After soaking the seeds, they trimmed the ends, bored and cleaned the seeds, and parched and blackened them in fire. Some seeds were decorated or polished to create beads for necklaces, belts, skirts, and aprons to wear at dances. Many southern coastal peoples, including the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw, traded with California communities for beads, which have been found in archaeological sites dated to about 1600 C.E. and were popular through the period of contact with Euro-Americans. Some anthropologists have suggested that pine nut beads were a form of “women’s money” and may have functioned as a trade item comparable to currency or as visual displays of wealth. Today, the beads are used in jewelry, aprons, and ceremonial regalia.

-

![]()

Whitebark pine cone, 2009..

Courtesy Bryant Olsen -

![]()

Indian Kate wearing pine nut apron, c.1900.

Courtesy Coos Historical and Maritime Museum, 995-D184 -

![]()

Ponderosa pine seeds.

Courtesy Molly Carney

-

![]()

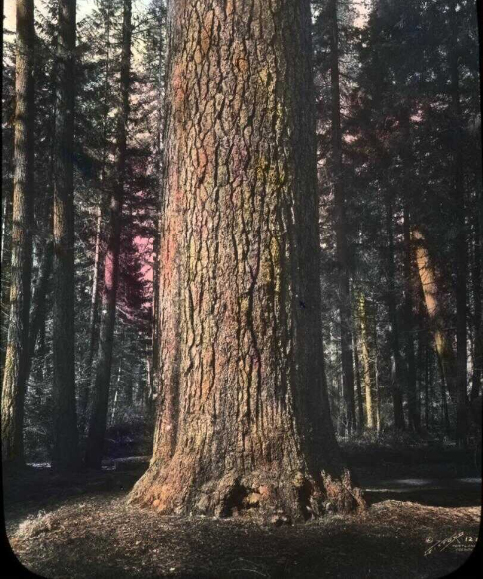

Brown ponderosa pine cone with trees in the background.

Courtesy Molly Carney

-

![]()

Whitebark pine, Mt. Howard, Wallowa Mountains, September 2023.

Courtesy Tania Hyatt-Evenson

Related Entries

-

![Camas]()

Camas

Camas is a North American bulb-forming geophyte whose greatest diversit…

-

![Dogbane (hemp)]()

Dogbane (hemp)

Dogbane (Apocynum sp.) is a short herbaceous plant whose name refers to…

-

![Ponderosa pine]()

Ponderosa pine

Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa)—also known as yellow, western yellow, …

-

![Salal]()

Salal

Both Meriwether Lewis and William Clark wrote about salal (Gaultheria s…

-

![Sugar pine]()

Sugar pine

Sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana) is one of the great conifers of the west…

-

Whitebark pine

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is arguably Oregon's quintessential t…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Anderson, Kat. Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California's natural resources. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Farris, Glenn J. "'Women's Money': Types and Distributions of Pine Nut Beads in Northern California, Southern Oregon, and Northwestern Nevada." Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 14.1 (1992): 55-71.

Hunn, Eugene S., with James Selam and family. Nch'i-Wana," The Big River": Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1990.

Mastroguiseppe, Joyce. "Nez Perce Ethnobotany: A Synthetic Review." Report to Nez Perce National Historical Park Project #PX9370-97-024, Spaulding, Idaho, 2000.

Ramsey, Jarold. Coyote was going there: Indian literature of the Oregon country. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1980.

Turner, Nancy J. Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America. Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2014.

Whereat Phillilps, Patricia. Ethnobotany of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2016.