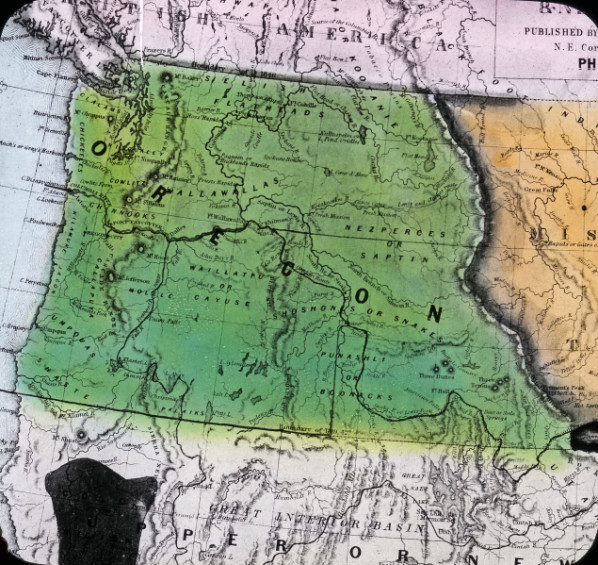

The Oregon Rangers, an organized militia based in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, was the first nonindigenous armed force in the Pacific Northwest. The Provisional Government created the unit on March 9, 1844, to protect the nascent Anglo-American community from potentially hostile Indigenous groups in the aftermath of the Cockstock Incident. The Oregon Rangers disbanded in June 1846, the same month the United States claimed full ownership of Oregon following the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain.

The Americans who began arriving in the Willamette Valley in the fall of 1843 experienced relatively calm relations with the Natives of the region. One notable exception occurred on March 4, 1844, when an armed Wasco named Cockstock rode into Oregon City accompanied by five Molalla men. Cockstock was in Oregon City to protest the hundred-dollar reward that U.S. subagent for Indian Affairs Elijah White had issued for his capture because of various crimes, including stealing a horse and vandalizing White’s home. Soon after Cockstock arrived, a few armed settlers assembled at a nearby sawmill, some of whom apparently hoped to collect the reward. Amid rising tensions, Cockstock’s band and several townspeople engaged in open combat, resulting in the death of Cockstock and two settlers, George LeBreton and Sterling Rodgers.

To avoid further bloodshed, White enlisted Chief Factor John McLoughlin of the Hudson’s Bay Company to compensate Cockstock’s widow by providing her with gifts in accordance with a Native practice known as "covering the dead," but many resettlers doubted that the tactic would prevent future violence. On March 9, 1844, members of the Provisional Government voted to form a voluntary militia of twenty-five mounted riflemen, led by Thomas D. Keizur, to pursue Cockstock’s Molalla accomplices. The Oregon Rangers assembled on March 11, but Cockstock’s supporters remained at large. Relations between Natives and settlers, however, remained peaceful, and the Oregon Rangers saw no action in subsequent months. Some nineteenth-century historians, including Frances Fuller Victor, have suggested that the militia was also intended to project U.S. power by sending a strong message to the Hudson’s Bay Company, which represented Great Britain in the region.

In May 1846, several prominent Oregonians held a meeting at legislator Daniel Waldo’s home in the Champoeg District to form a second militia, also known as the Oregon Rangers. Later that summer, that militia was involved in a skirmish at Battle Creek, near Salem. Responding to unsubstantiated rumors that Wascos were stealing cattle from a local settler, an Oregon Ranger shot and wounded a Wasco man without receiving orders. The militia compensated the Wasco victim with a pony and two blankets, but the Oregon Rangers’ reputation was tarnished and they soon disbanded.

-

![]()

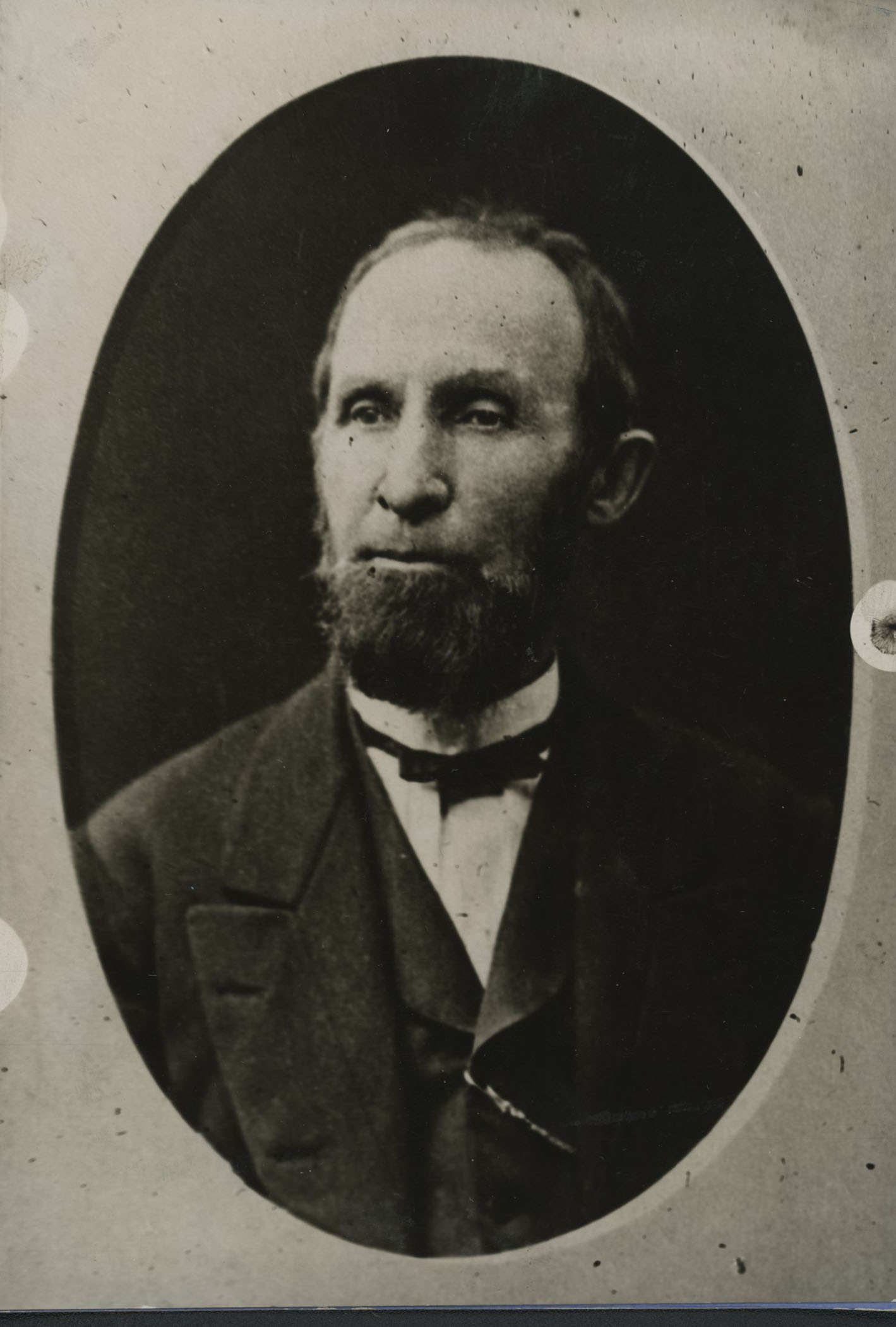

Elijah White.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi728

-

![]()

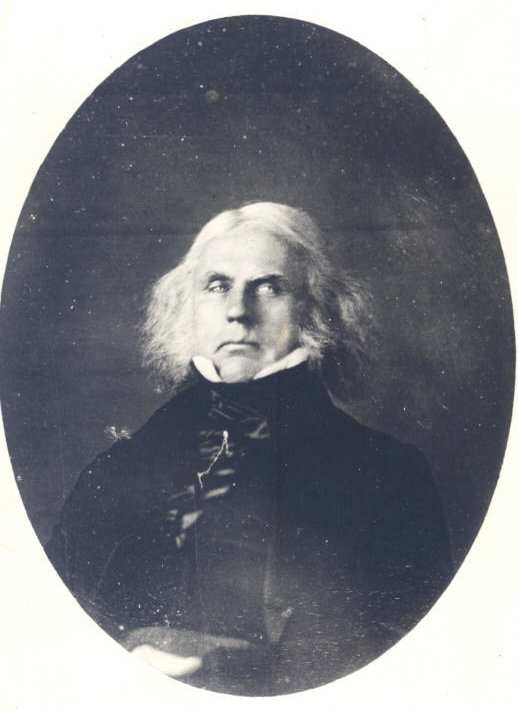

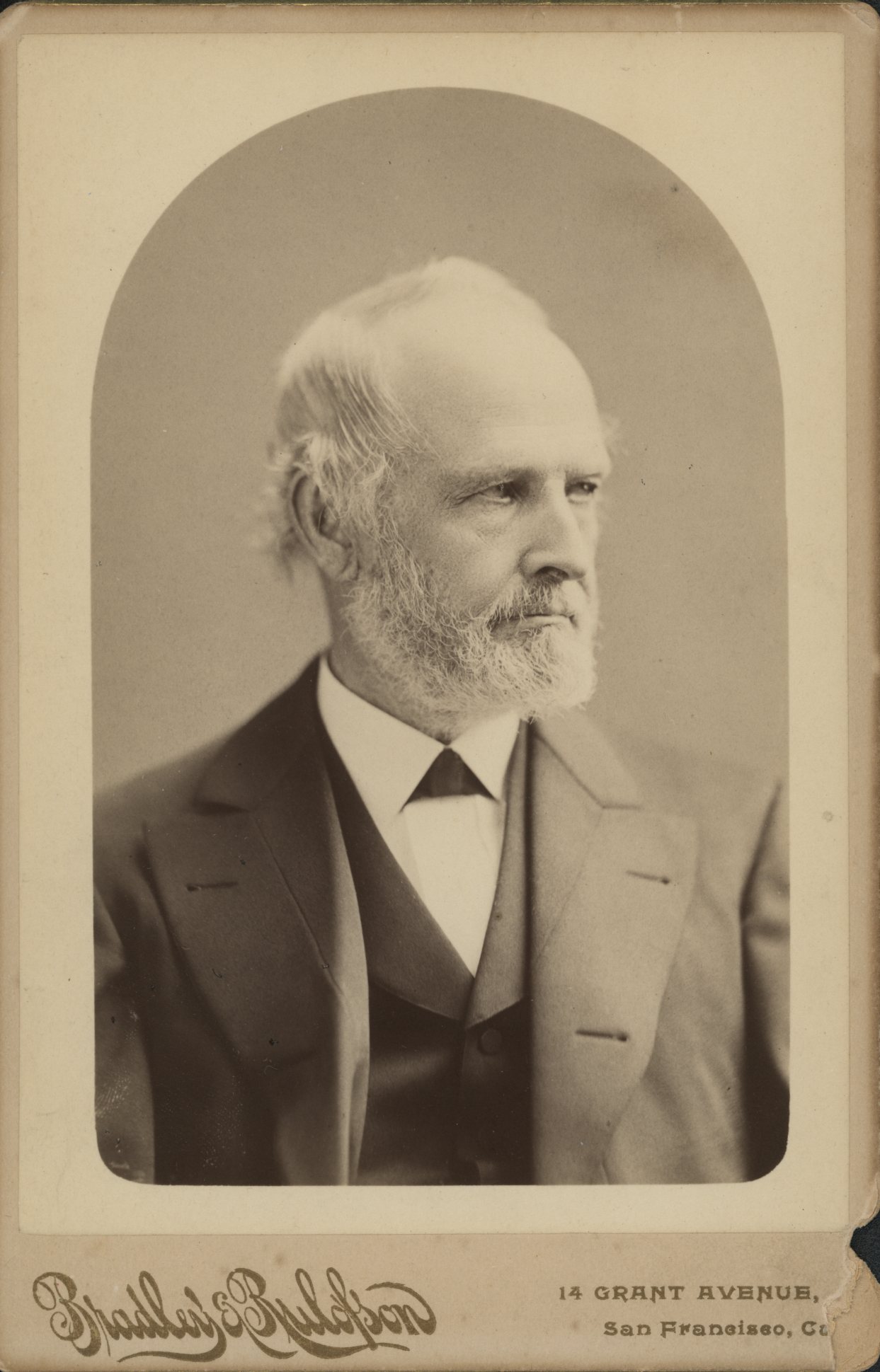

Dr. John McLoughlin.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi73380

-

![]()

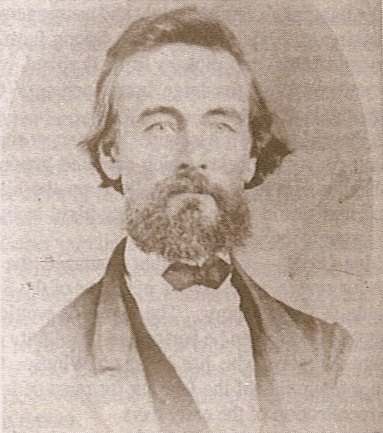

Thomas D. Keizur.

Courtesy Keizer Times

-

![]()

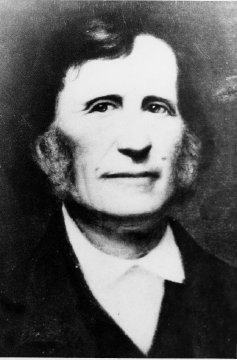

Daniel Waldo.

Courtesy Oregon State Library

Related Entries

-

![Cockstock Incident]()

Cockstock Incident

The Cockstock Incident in 1844, also known as the Cockstock Affair, was…

-

![Elijah White (1806-1879)]()

Elijah White (1806-1879)

Among early migrants to the Oregon Country from the United States, Elij…

-

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

-

![Peter Burnett (1807-1895)]()

Peter Burnett (1807-1895)

Peter Hardeman Burnett was a leader on the Oregon Trail, a town-builder…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Clarke, Samuel Asahel. Pioneer Days of Oregon History, Volume Two. Portland Ore.: J.K. Gill Company, 1905.

Gray, William Henry. A History of Oregon, 1792-1849 Drawn From Personal Observation and Authentic Information. Portland, Ore.: Harris and Holman, 1870.

McClintock, Thomas C. "James Saules, Peter Burnett, and the Oregon Black Exclusion Law of June 1844." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86.3 (July 1995): 121-130.

Victor, Frances Fuller. The Early Indian Wars of Oregon: Compiled from the Oregon Archives and Other Original Sources, with Muster Rolls. Salem, Ore.: Frank C. Baker, State Printer, 1894.