The Cockstock Incident in 1844, also known as the Cockstock Affair, was the most significant occurrence of violence between white immigrants and the Oregon Country’s Indigenous residents prior to the Whitman murders in 1847. The confrontation resulted in three deaths and contributed to the formation of the Oregon Rangers, the first nonindigenous military organization in the Pacific Northwest. Some historians have suggested that the event heightened white settlers' antipathy toward Blacks and may have contributed to Oregon’s Black exclusion laws.

The confrontation between townspeople in Oregon City and a group of Molallas, led by a man named Cockstock (who was often referred to as a Wasco), had its origins almost a year earlier in a disagreement between Cockstock and a Black settler named James D. Saules, who had purchased a farm and a horse from Winslow Anderson, a man of African and European ancestry. Anderson evidently had promised the same horse to Cockstock in exchange for his labor. In April 1843, Cockstock had ridden to Saules’s farm near Oregon City and demanded that he relinquish the horse. When Saules refused, Cockstock seized the horse and for several months harassed both Saules and Anderson.

In February 1844, Saules reported Cockstock’s activities to U.S. Indian Subagent Elijah White, who was already involved in a protracted feud with Cockstock. The Oregon Country was not part of the United States at the time, and White was the only federal authority in the region. More than a year earlier, in November 1842, White had visited tribal members throughout the region to issue a new civil compact intended to regulate their behavior. In November 1843, Cockstock had gone to White’s home intending to assassinate him in retaliation for his role in whipping a Wasco headman charged with theft, but White was away. In December, Cockstock and five Molallas had allegedly killed a group of Molalla and Klamath men for entering into friendly negotiations with White. In February, White offered a $100 reward for Cockstock’s capture and assembled a posse to pursue him.

On the early afternoon of March 4, 1844, Cockstock and five Molalla supporters arrived in Oregon City on horseback, carrying firearms and bows. Contemporaneous accounts vary regarding his motives for coming to town. Some claimed he was there to menace and harass, while others insisted he was attempting to establish that he was innocent of White’s allegations. Cockstock and the men brandished loaded pistols and rode through the streets for several hours, apparently alarming the townspeople. The group then went to a nearby village, where Cockstock spoke with a headman.

Returning to Oregon City, they exchanged gunfire with settlers there, although it is unclear who fired first. During the mêlée, Cockstock shot and stabbed George LeBreton, the official recorder for the Oregon Provisional Government, who later succumbed to blood poisoning. Winslow Anderson smashed Cockstock’s skull with his rifle barrel, killing him instantly. In retaliation, the Molallas shot William H. Willson and Sterling Rodgers before escaping; Rodgers died of his wound.

In the aftermath of the violence, many settlers feared a major revolt by the Indians. White eased tensions by emulating the Indigenous custom of “covering the dead,” presenting gifts of two blankets, a dress, and a handkerchief to Cockstock’s family. On March 9, 1844, the executive committee of the Provisional Government formed the Oregon Rangers, a twenty-five-member volunteer militia. The settlers did so in anticipation of a conflict with local Indigenous groups that never materialized.

-

![]()

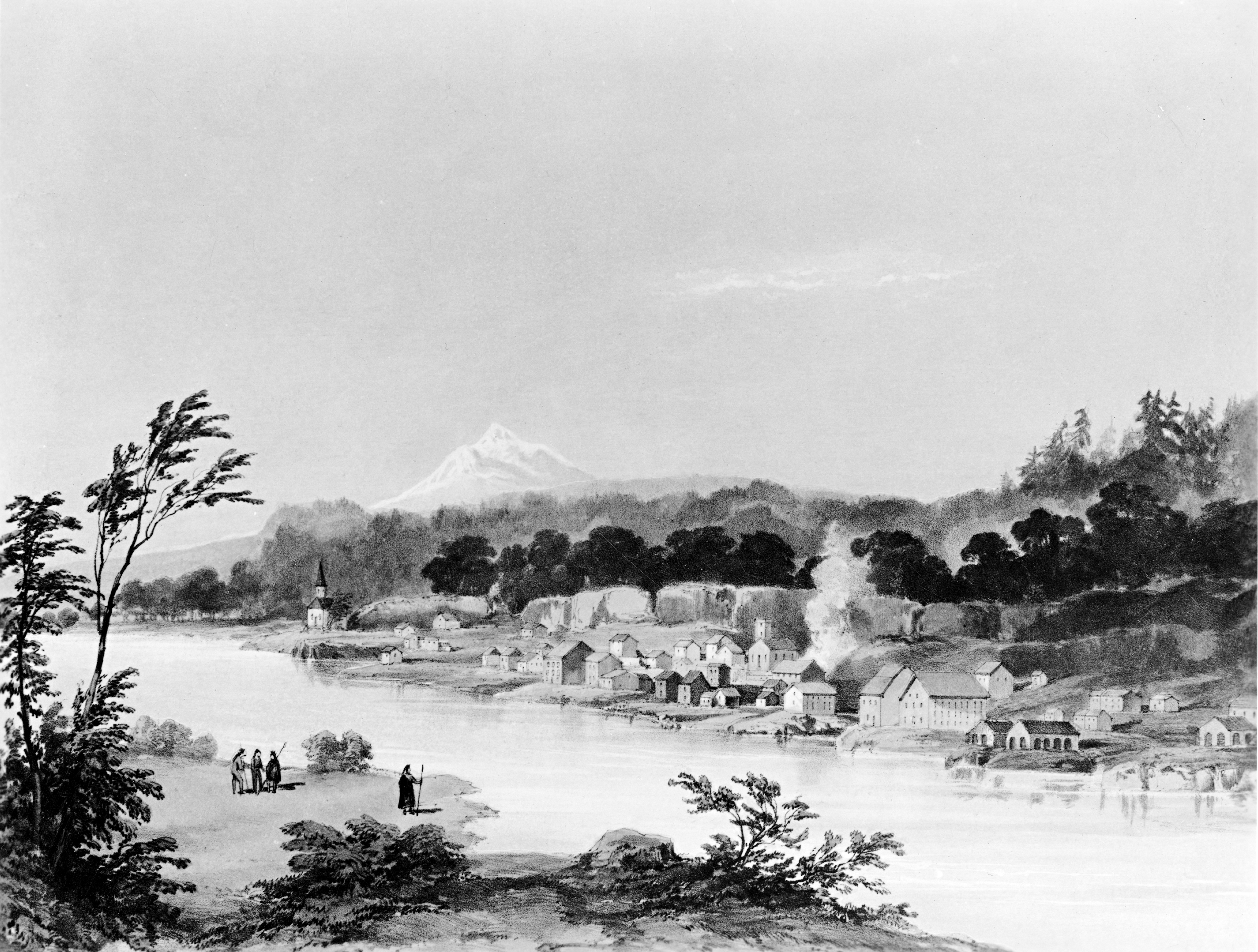

The Willamette River separates Linn City (foreground) and Oregon City, 1867.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Carleton Watkins, bb000072

-

![]()

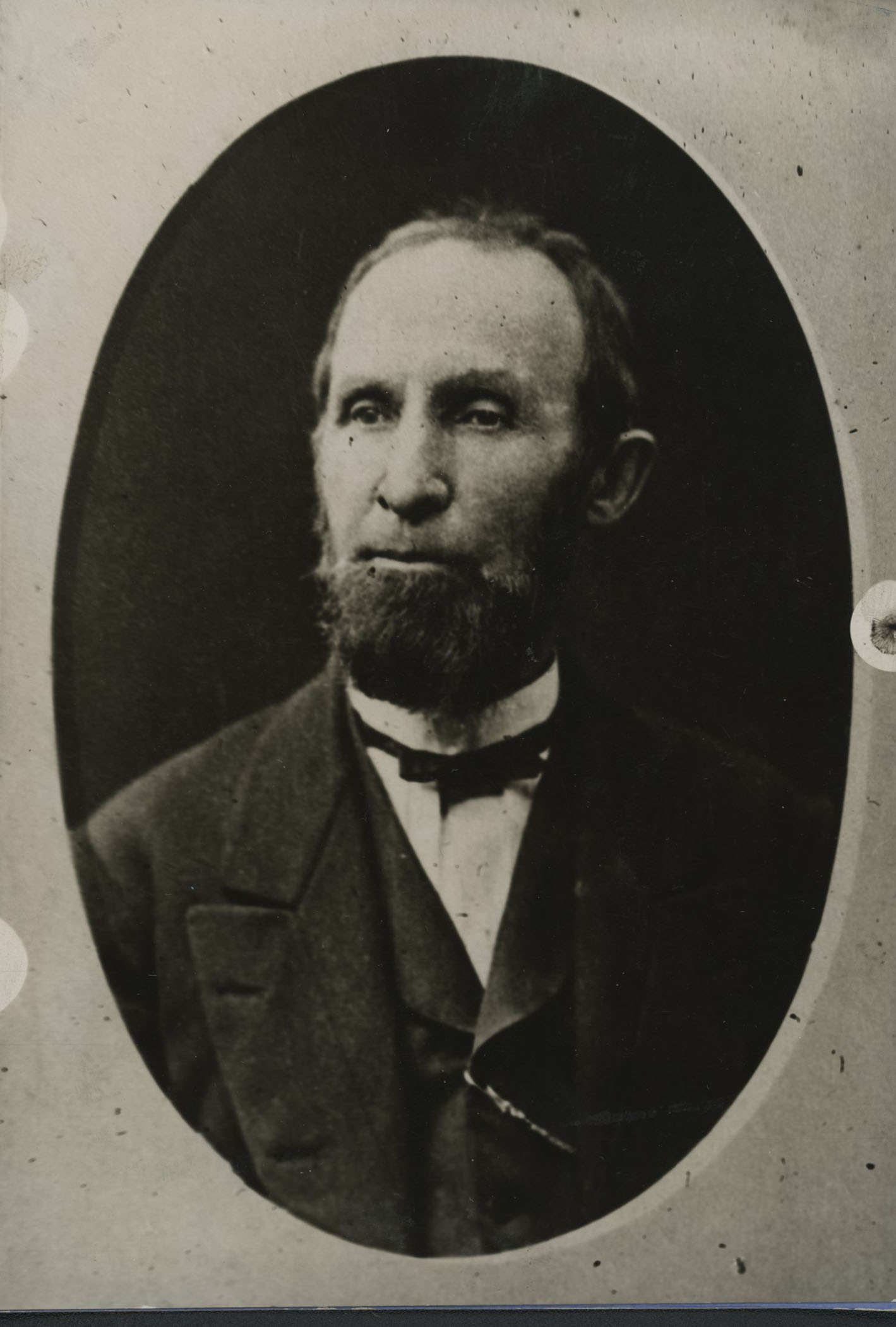

Elijah White.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi728

-

![]()

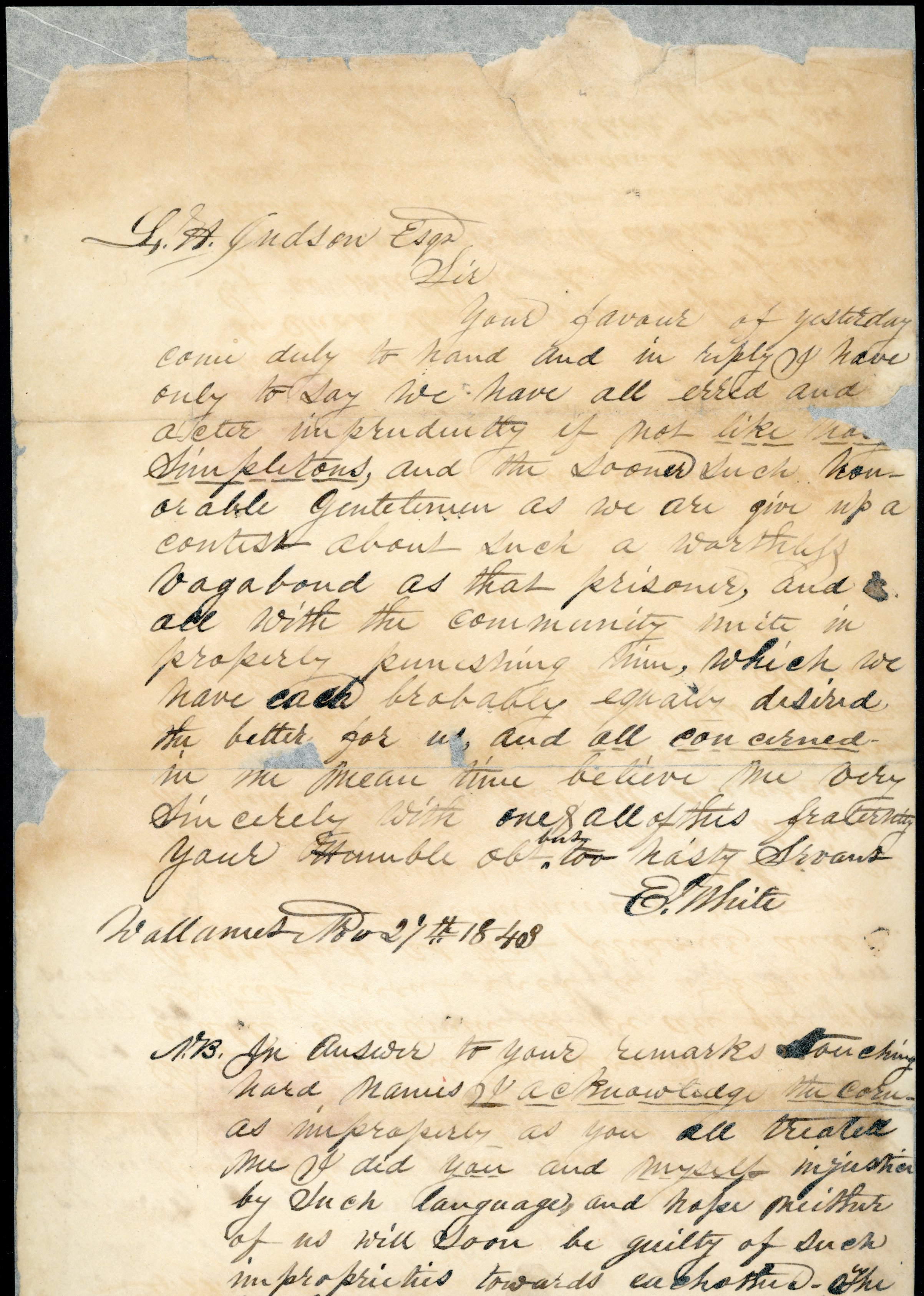

Letter from White to L.H. Judson, Nov. 21, 1843, regarding the handling of a Native American prisoner (first page).

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 976, folder 1

-

![]()

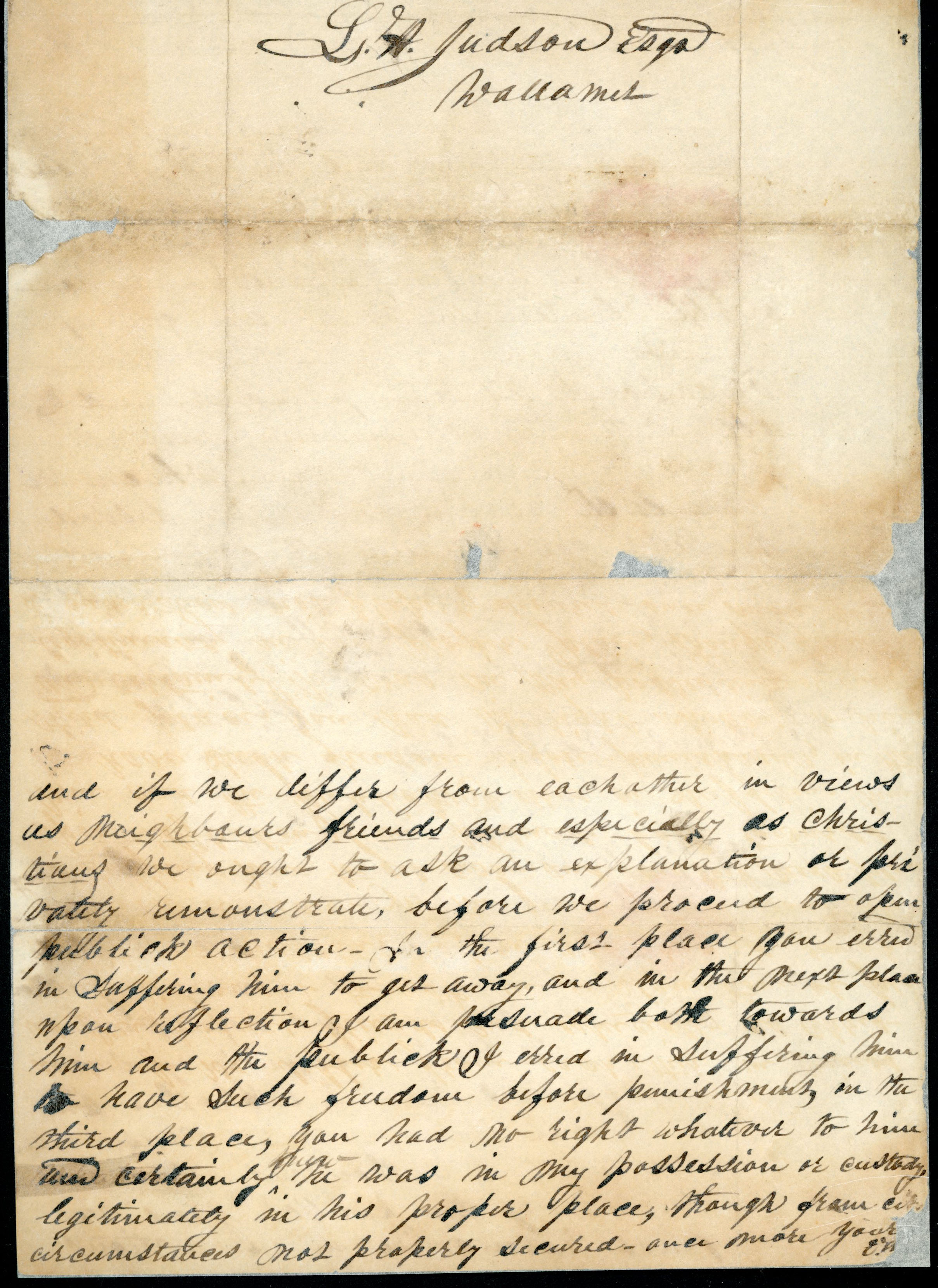

Letter from White to L.H. Judson, Nov. 21, 1843, regarding the handling of a Native American prisoner (second page).

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 976, folder 1

Related Entries

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Elijah White (1806-1879)]()

Elijah White (1806-1879)

Among early migrants to the Oregon Country from the United States, Elij…

-

![James D. Saules (1806?–1850s)]()

James D. Saules (1806?–1850s)

James D. Saules was a Black American sailor and musician who arrived in…

-

![Oregon Rangers]()

Oregon Rangers

The Oregon Rangers, an organized militia based in Oregon’s Willamette V…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Blanchet, Francis Norbert. Historical Sketches of the Catholic Church in Oregon, During the Past Forty Years. Portland: Catholic Sentinel Press, 1878

Coleman, Kenneth R. Dangerous Subjects: James D. Saules and the Rise of Black Exclusion in Oregon. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2017

McClintock, Thomas C. "James Saules, Peter Burnett, and the Oregon Black Exclusion Law of June 1844." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86.3 (July 1, 1995): 121-130.

Victor, Frances Fuller. The Early Indian Wars of Oregon: Compiled from the Oregon Archives and Other Original Sources, with Muster Rolls. Salem, Ore.: Frank C. Baker, State Printer, 1894.