When Obed Dickinson arrived in Salem in 1853 to become pastor of the Congregational Church, he found himself in a city where many opposed slavery but few were sympathetic to the idea of Black equality. The Oregon Provisional Government had passed Black exclusion laws as early as 1844, and voters in 1857 would overwhelmingly support a provision in the state constitution excluding Blacks. But Dickinson was, as the Oregon Northwest Black Pioneers wrote in its history of Blacks in the Salem area, “far ahead of his fellow whites in his thinking about Black people, and he paid a price for it.”

Dickinson was born on June 15, 1818, in Amherst, Massachusetts. He grew up on a farm and attended Marietta College in Ohio before studying for the ministry at Andover Theological Seminary in Massachusetts. After he and Charlotte Humphrey married in 1852, he accepted an assignment from the American Home Missionary Society to become the first Congregational minister in Salem. To reach the West Coast, the couple sailed around Cape Horn on the Trade Wind with seven other missionary couples bound for California and Oregon Territory.

The Dickinsons arrived in Salem in March 1853 to find a congregation with four members who met in a log schoolhouse with a dirt floor. They were not discouraged, however, and set to work building a house for themselves and enlarging their congregation. Obed Dickinson’s views on slavery were the same as those held by the Congregational Church. He helped organize other Oregon Congregational ministers into the Congregational Association of Oregon, which denounced slavery as morally wrong, opposed the extension of slavery into U.S. territories and states, and agreed to forbid ministers who owned slaves or were sympathetic to slavery to preach in their churches.

The 1860 census reported 7,088 residents in Marion County, twenty of whom were “free colored.” The area had been resettled by whites from Southern and Border states, especially Missouri, and they had brought their politics and racial prejudices with them. As Dickinson’s biographer Egbert Oliver wrote: “The dominant attitude in the state continued to be: save the union and the nation; let slavery alone where it existed; and keep ‘Negroes’ out of Oregon.”

On March 3, 1861, a day before Abraham Lincoln’s presidential inauguration and a little over a month before the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Dickinson welcomed nine new members to his congregation, three of them Black. It is thought that two of those members were Robin and Polly Holmes, who had been principles in the successful Holmes v. Ford lawsuit to free their enslaved children in 1853. Though the members of the church had agreed to accept the new members, one prominent parishioner asked that the service to admit the three Blacks be held separately from the service for the others, a request that Dickinson denied.

On June 16, Dickinson’s sermon strongly criticized excluding Black children from local schools, as was the case in Salem, saying it was “wrong to take away the key of knowledge from any human being.” Afterward, a church member warned the pastor: “That sermon will take away $500 from our church building [fund].” A year later, in July 1862, Dickinson reported to the American Home Missionary Society that Charlotte Dickinson, who had taught in Indiana for fifteen years before her marriage, was teaching four Black students in their home for two hours a day, including one “wife” and two “servant girls” who were learning to read.

By January 1863, things had reached a crisis with some members of Dickinson’s congregation, who believed that his actions and preaching were harming the church, which by then had thirty-seven members. On New Year’s Day, the Dickinsons hosted a wedding and party for Richard Bogle of Walla Walla and America Waldo of Salem, who were Black. The event caused a stir and elicited disapproving editorial comments in the Oregon Statesman, the Oregonian, and the San Francisco Bulletin.

Later that month, a meeting of church members passed a resolution asking Dickinson to “abstain from these exciting topics, slavery, etc. in his future labors with this church.” He offered his resignation, but no action by church members was taken. At the annual meeting of the congregation in February, Dickinson defended his actions: “In our own land, slavery is now the crying sin which God is dealing with….While other sins may be reproved also, no minister of the Gospel can leave this subject entirely out of the Pulpit, and do his duty to God.”

The congregation voted in March 1863 not to reappoint Dickinson, but by June they were unable to find a new pastor so decided to leave him in his pulpit. Still, Dickinson’s difficulties continued. In October 1864, when he once again attempted to end his appointment, the congregation refused to accept it. Finally, in March 1867, his tenure came to an end when a new minister, Plutarch Knight, was hired.

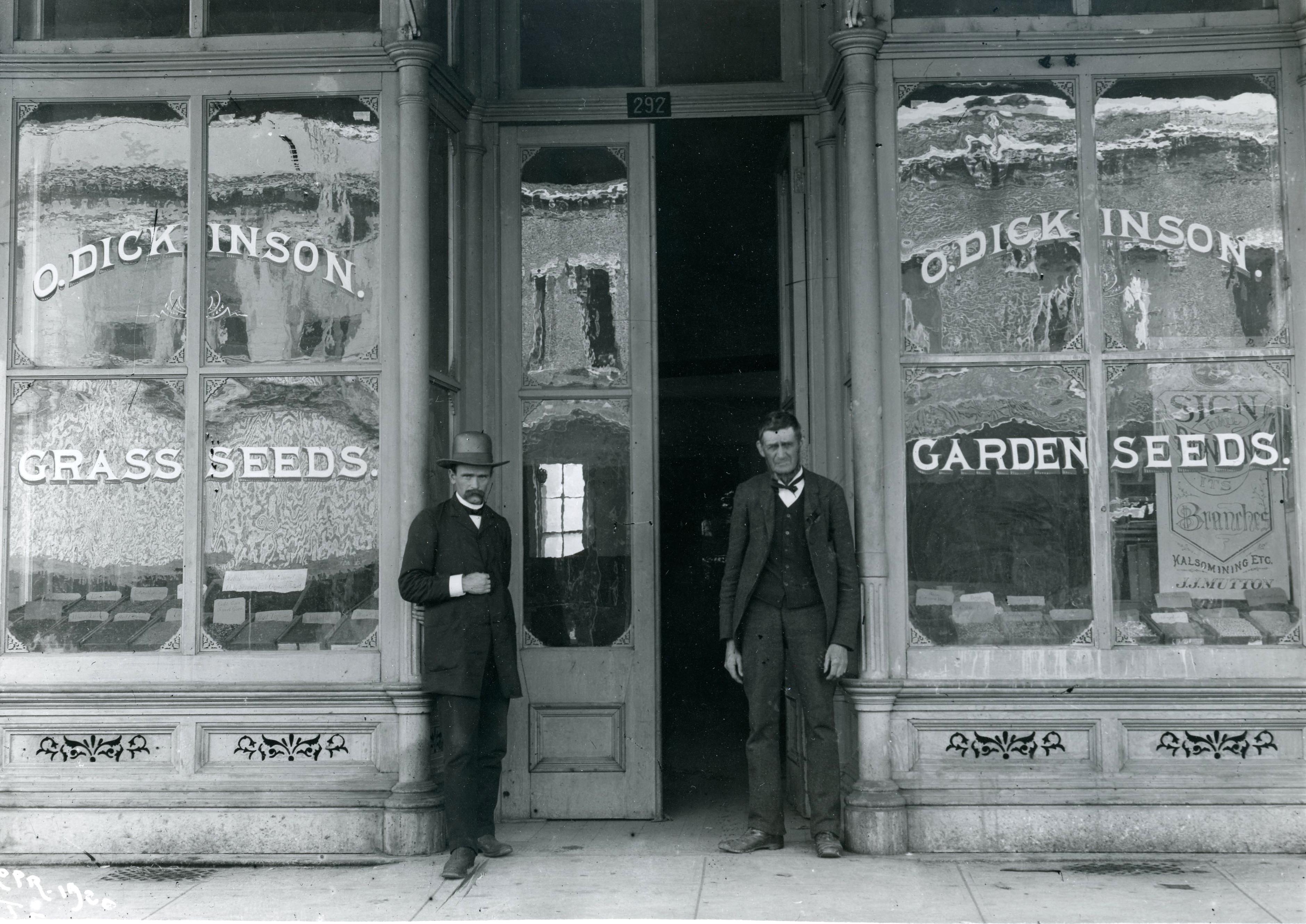

At the same time that Dickinson was continuing his tenuous ministry, he managed to develop a successful nursery and seed business on a twenty-one-acre farm. After he left the ministry, O. Dickinson Garden and Field Seeds became a lucrative business in downtown Salem. Dickinson became a respected civic leader and served as a director of the public schools, as well as a trustee for Willamette University and Pacific University. Late in life, he left the Congregational Church, became a Seventh Day Adventist, and helped organize a small congregation in Salem.

He and Charlotte had three children, only one of whom survived childhood, and one adopted child. Obed died in 1892, and Charlotte died in the following year. Both are remembered in Salem for their commitment to racial justice.

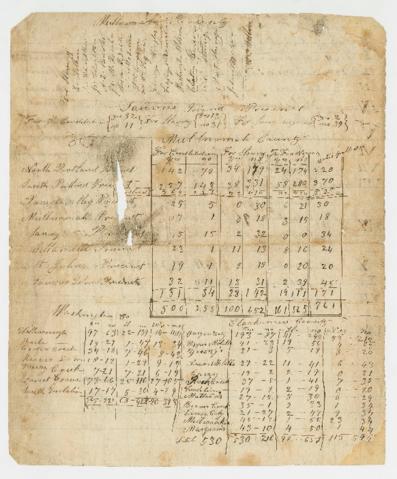

-

![]()

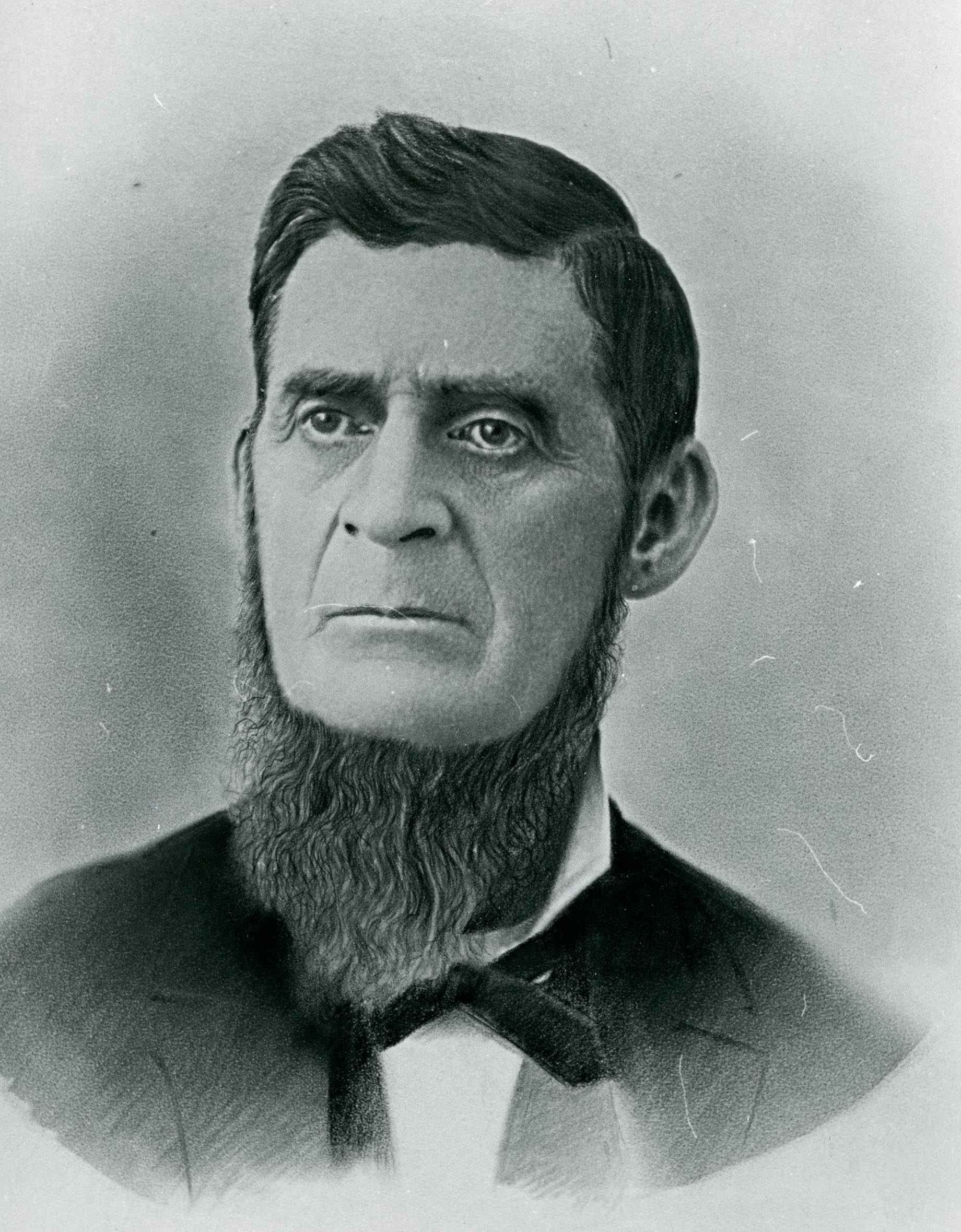

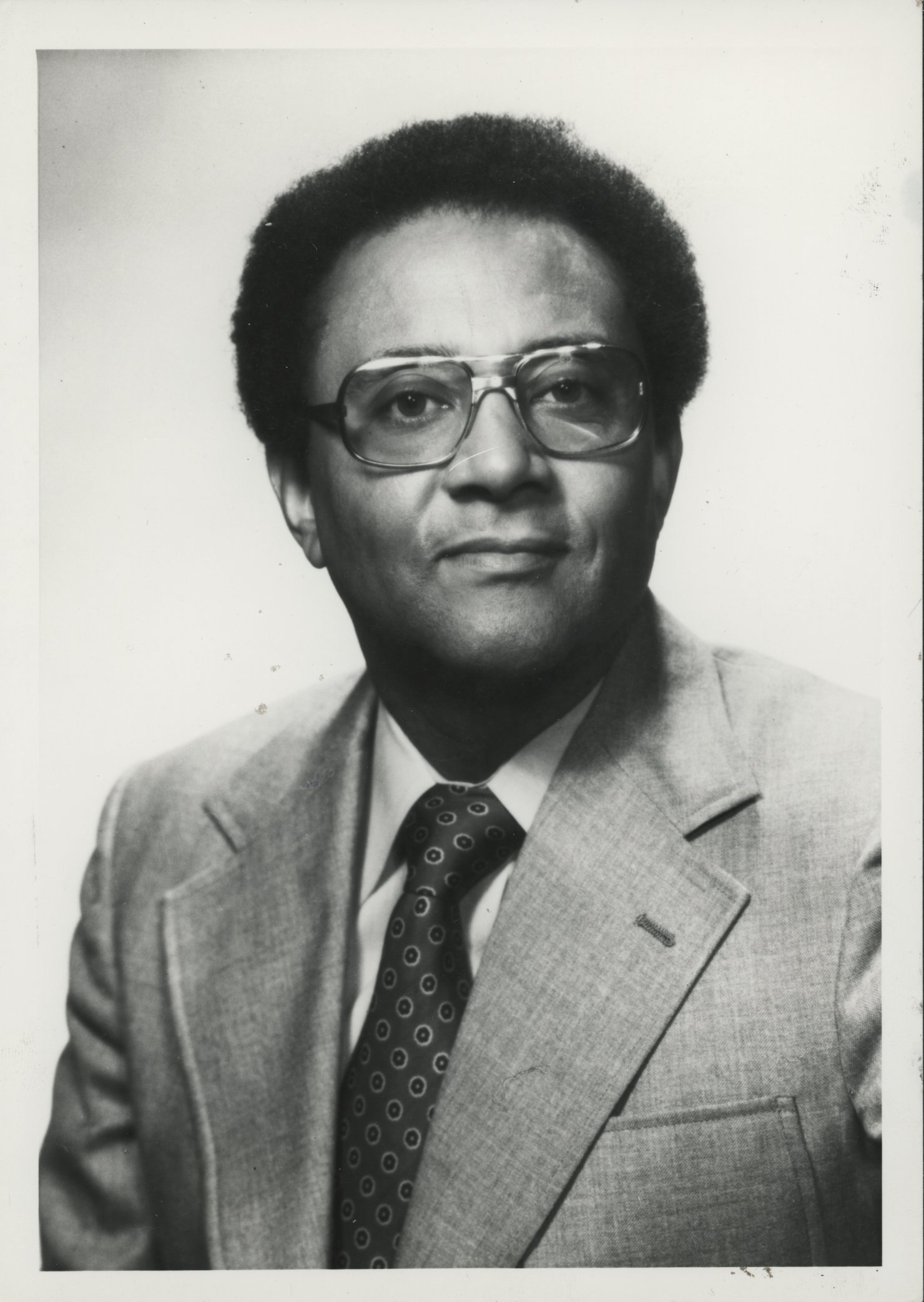

Obed Dickinson.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi298, photo file 330

-

![Rev. Robert Whitaker on the left.]()

Obed Dickinson (right) in front of his Salem seed store..

Rev. Robert Whitaker on the left. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 0181G013, photo file 330

-

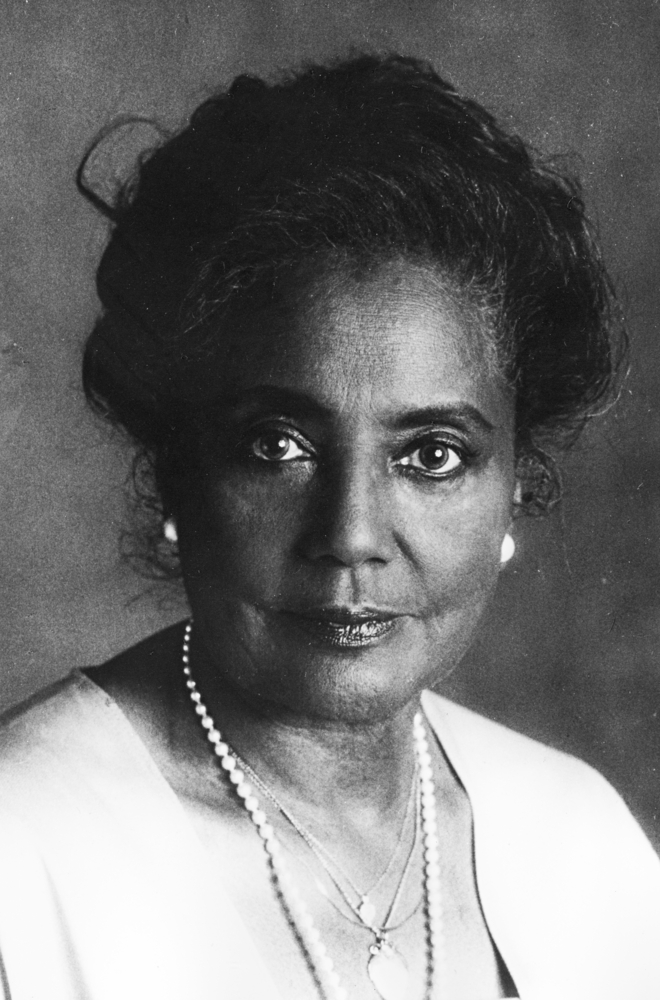

![]()

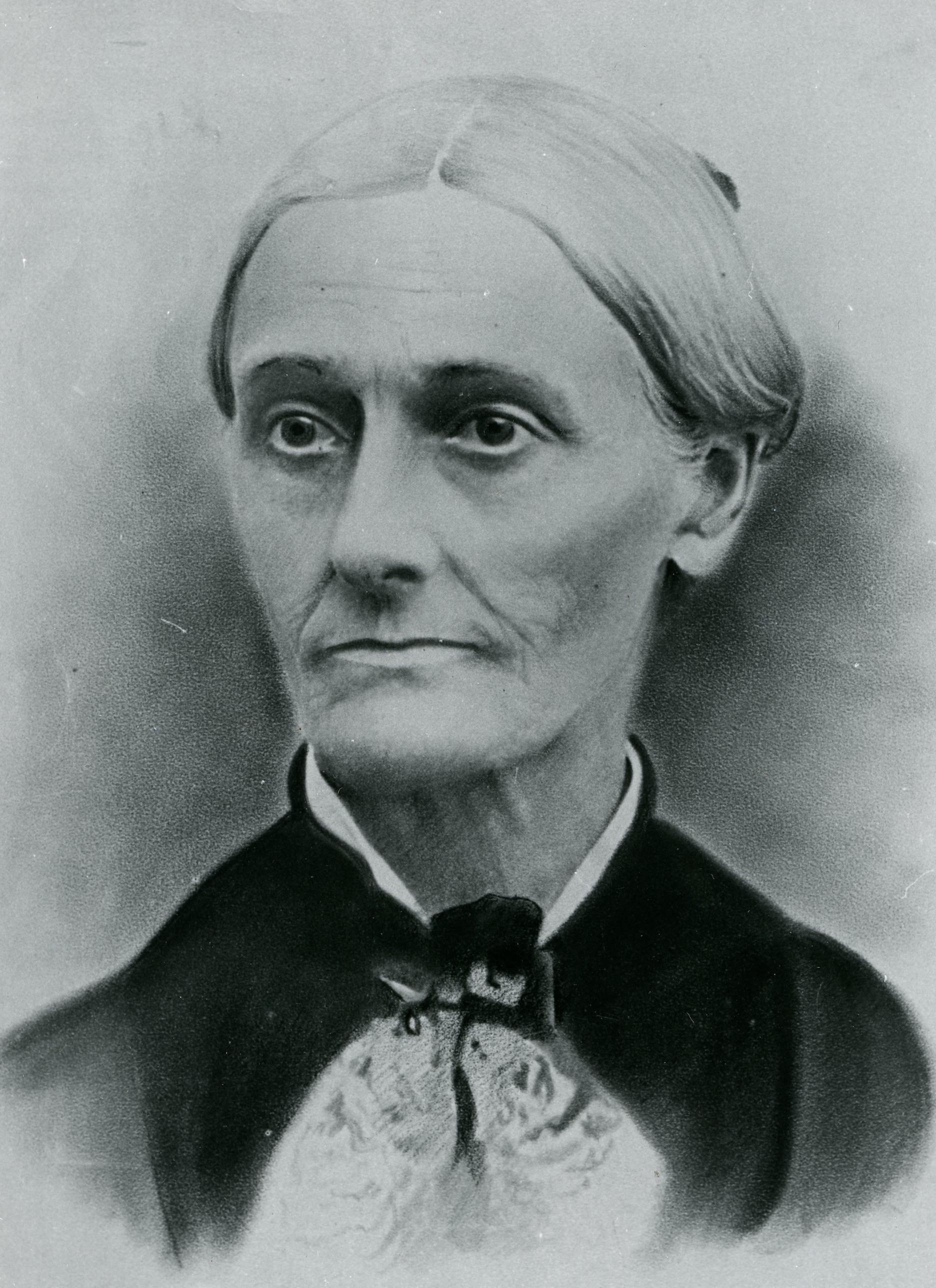

Charlotte Dickinson.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi299, photo file 330

-

![]()

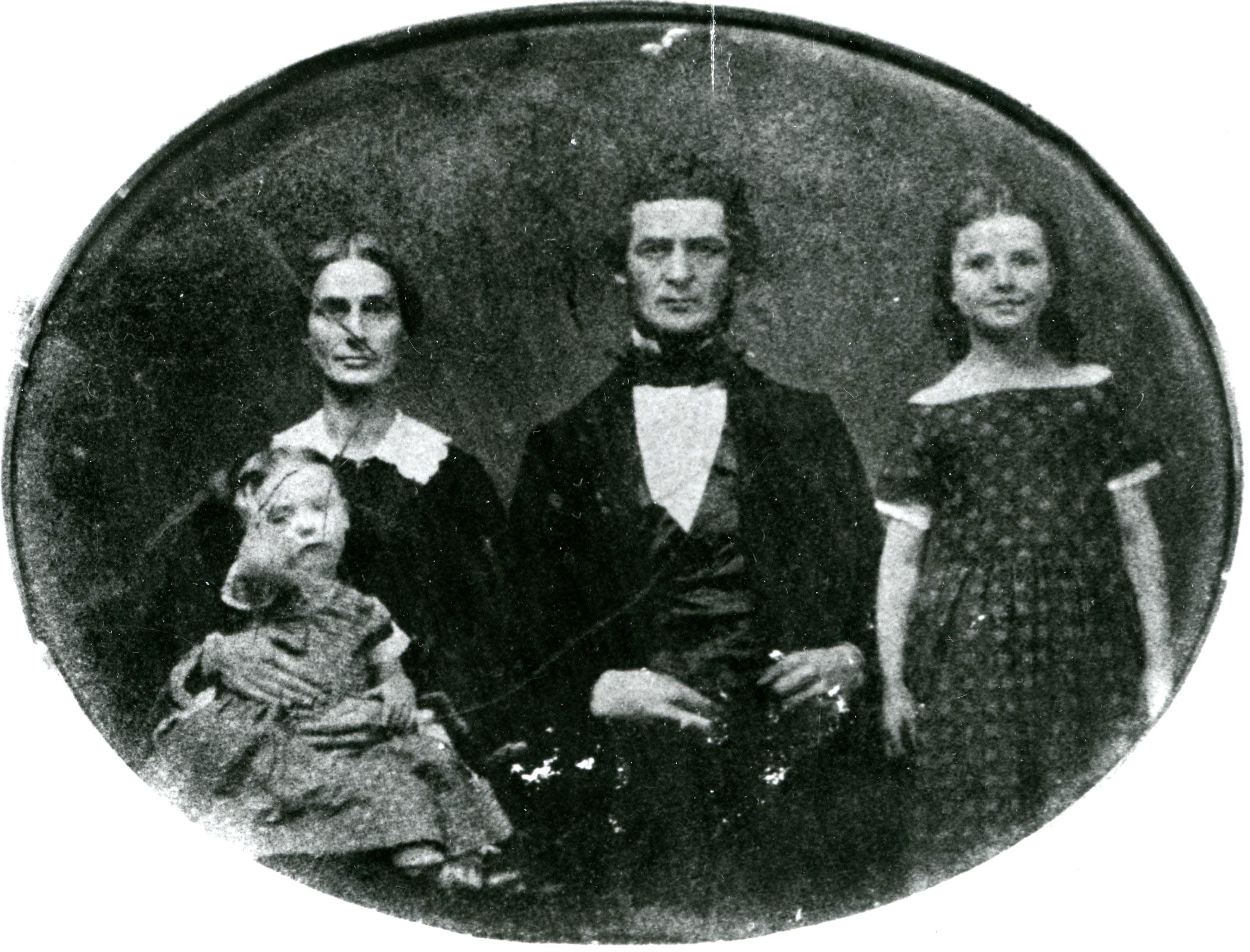

Charlotte and Obed Dickinson, with children.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 63537, photo file 330

-

![]()

First Congregational Church, Liberty and Center Streets, Salem.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0218G026

Related Entries

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![City of Salem]()

City of Salem

Salem, the capital of Oregon, is located at a crossroads of trade and t…

-

![Holmes v. Ford]()

Holmes v. Ford

On April 16, 1852, a former slave named Robin Holmes filed suit against…

-

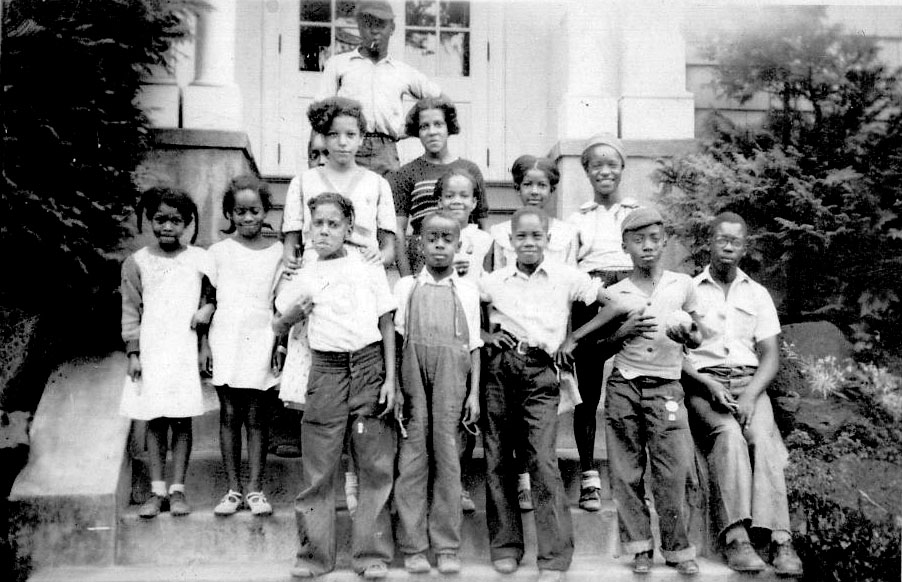

![Kathryn Hall Bogle (1906 - 2003)]()

Kathryn Hall Bogle (1906 - 2003)

A freelance journalist, social worker, and community activist, Kathryn …

-

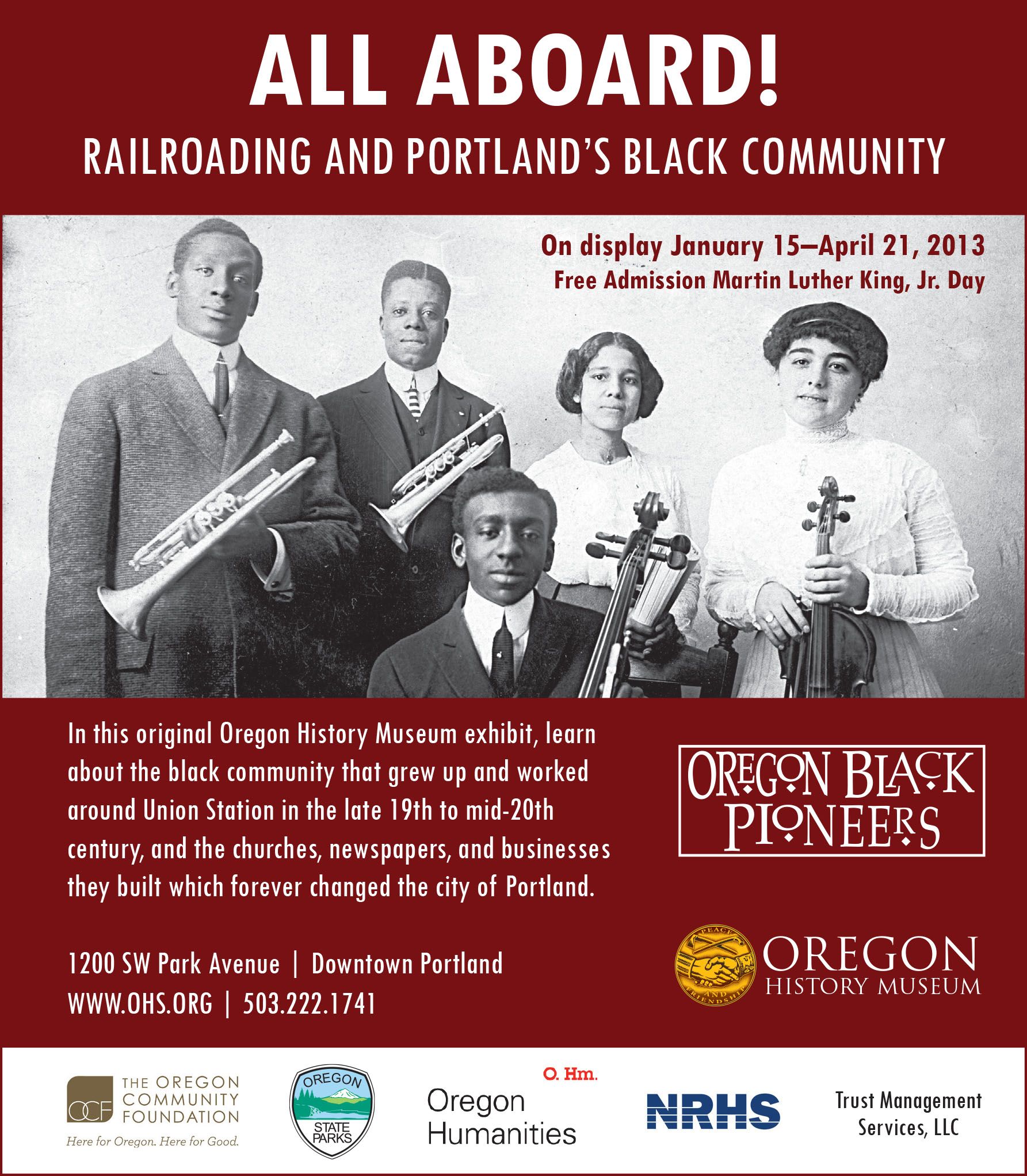

![Oregon Black Pioneers (organization)]()

Oregon Black Pioneers (organization)

Oregon Black Pioneers, an all-volunteer group founded in Salem in 1993,…

-

![Richard “Dick” Bogle (1930–2010)]()

Richard “Dick” Bogle (1930–2010)

Dick Bogle was a multi-talented Oregonian and humanitarian who dedicate…

-

![Salem's Colored School and Little Central]()

Salem's Colored School and Little Central

The first school open to African American students in Oregon—referred t…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

McCarthy, Sheridan, and Stanton Nelson. Perseverance: A History of African Americans in Oregon's Marion and Polk Counties. Salem: Oregon Northwest Black Pioneers, 2011.

Oliver, Egbert S. “Obed Dickinson and the ‘Negro Question’ in Salem.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 92.1 (1991): 5–6.

Oliver, Egbert S. Obed Dickinson's War Against Sin in Salem, 1853 - 1867. Portland, Ore.: The Hapi Press, 1987.