John Day was an American hunter who came to Oregon in 1812 as a straggler from the Pacific Fur Company’s overland expedition to Astoria. Little is known of his life, including his eight years in the Oregon Country, but his name appears on more Oregon geographic features, towns, institutions, and structures than any other person from the fur trade era.

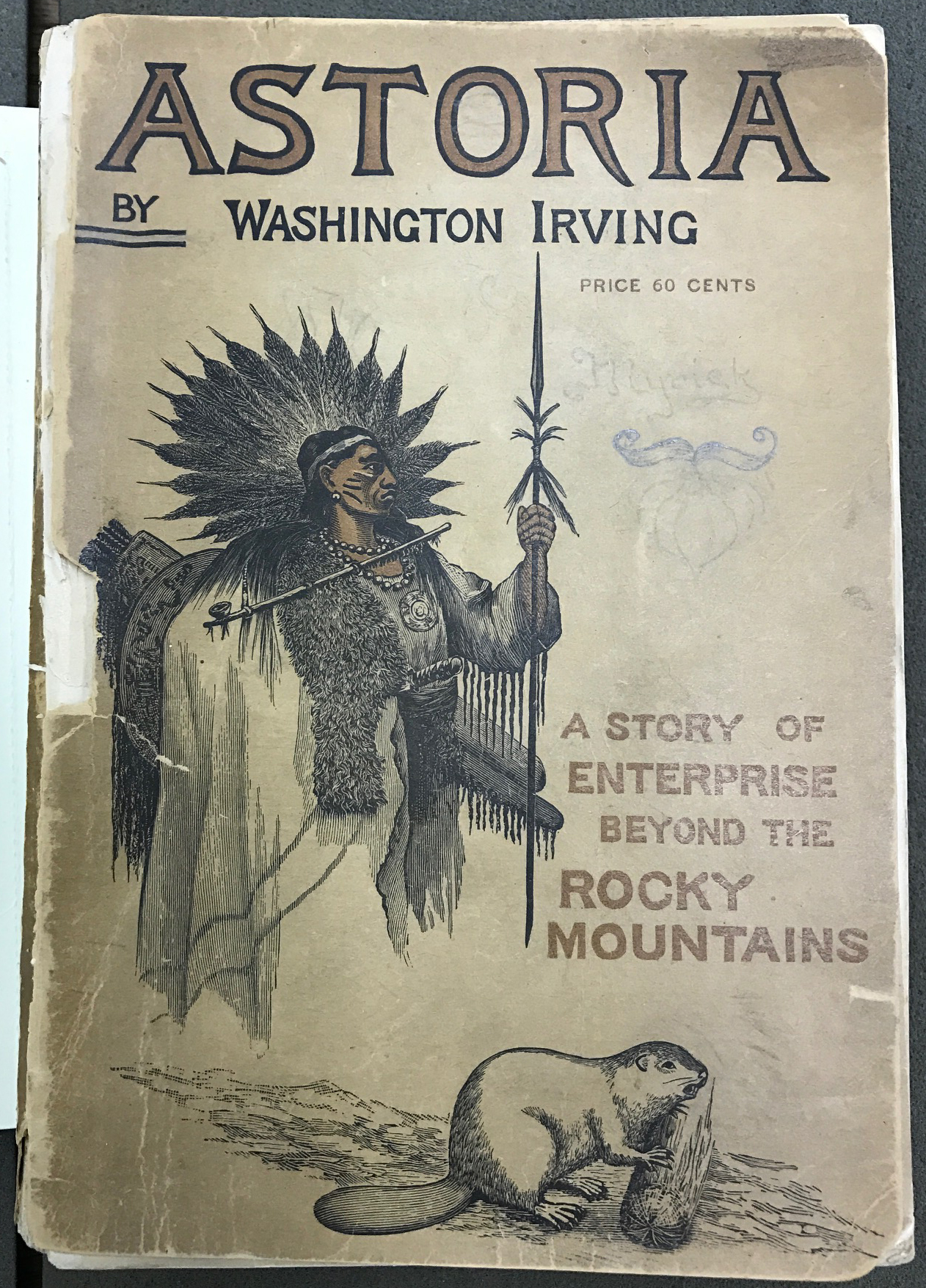

Born in about 1770 in Virginia, Day lived in Kentucky before moving to Missouri, where, beginning in 1798, he petitioned for and received two land concessions, about 800 acres, from the Spanish government. He hunted, trapped, and farmed for a living and in 1809 established a saltpeter mining operation. Writer Washington Irving described him in Astoria: Anecdotes of an Enterprise beyond the Rocky Mountains (1836) as tall with a “handsome, open, manly countenance.” At forty years old, he was “a prime woodsman, and an almost unerring shot” with “an elastic step as if he trod on springs.”

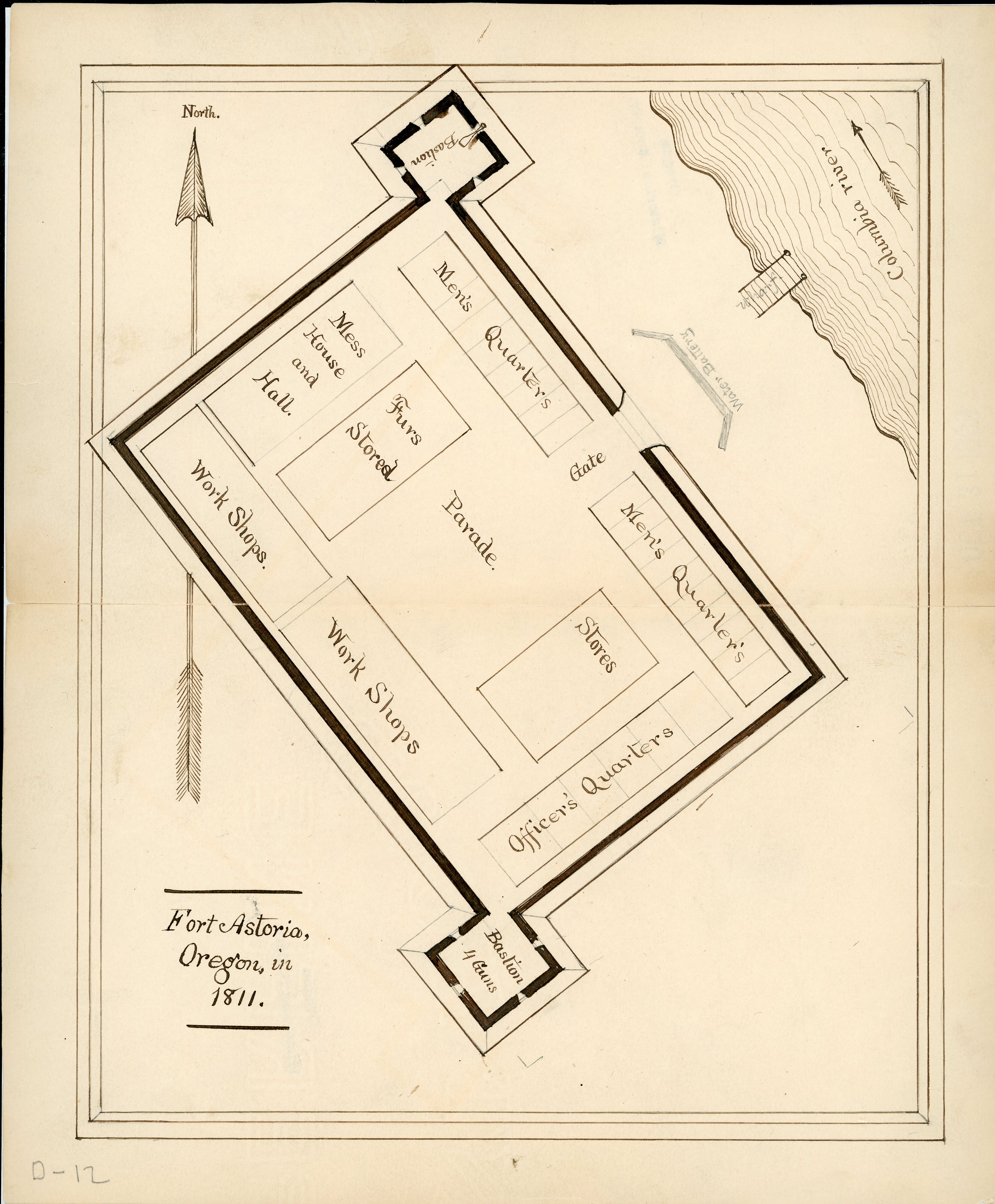

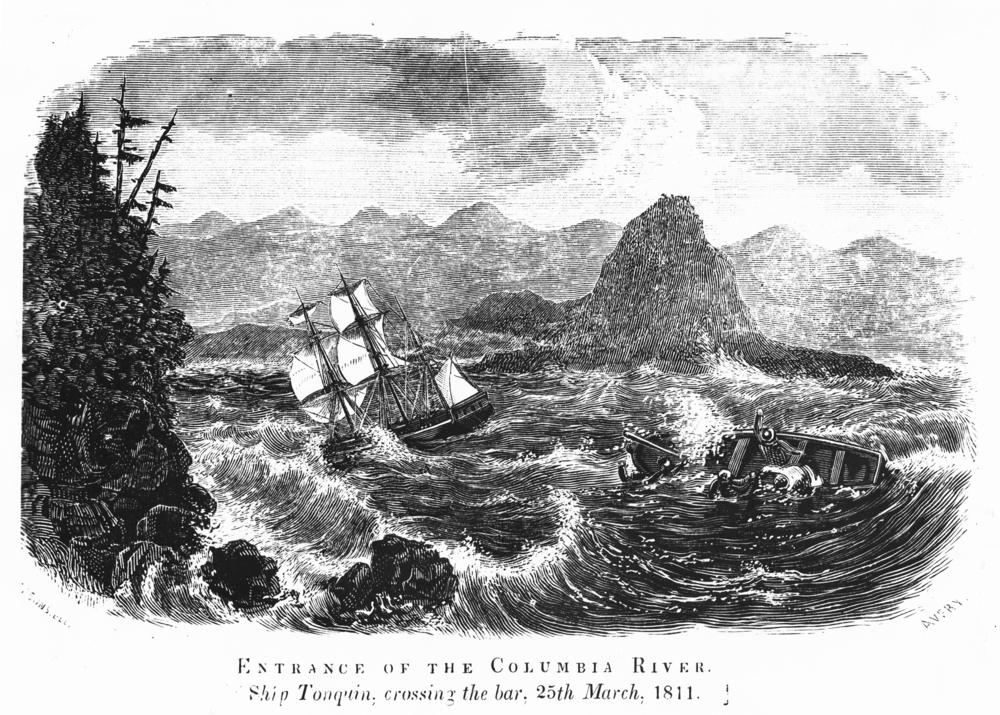

In November 1810, near the winter quarters for the Pacific Fur Company on the Nodaway River, Day joined the company’s overland expedition to what is now Astoria. Left behind in present-day Idaho by the main overland party due to illness, Day and Ramsay Crooks entered the Oregon Country in 1812 on their way to Astoria to seek relief. In April, near the mouth of a large river that flows into the Columbia, the two men encountered a group of Natives who, in retaliation for a recent murder perpetrated by a company employee, took rifles and equipment from Crooks and Day, sparing their lives but stripping them naked. They were found upriver days later by a Pacific Fur Company party. The river near the site of the encounter became known by fur company employees as the John Day River.

Within two weeks, Day had recovered enough to begin work as a hunter for company employees at Fort Astoria. By June 29 he had resolved to leave, and he joined Robert Stuart and his party, who were bound for St. Louis. Two days out, Day began exhibiting behavior that Stuart described as delirious, troublesome, dangerous, and suicidal. Some days later, concluding that Day’s “insanity amounted to real madness,” Stuart reluctantly paid a Cathlapotle chief to return him to Astoria, along with a letter in which Stuart expressed “a doubt of the reality of his madness, whether it was not pretended as an excuse from performing the Journey.”

John Day arrived back in Astoria on August 9 “in good health without any appearance of having been crazy.” He explained his actions by saying that he had been treated “in so shameful a manner” by a Robert McClellan, a brigade officer, that he “might have acted as a madman as he really was for a while.” He “gave way to passion,” he said, and “exposed some certain facts and gave his mind freely, on which they endeavored to persuade him he was crazy.” From that incident grew later characterizations of Day as mad or insane, a description enhanced by Irving’s depiction of him in Astoria.

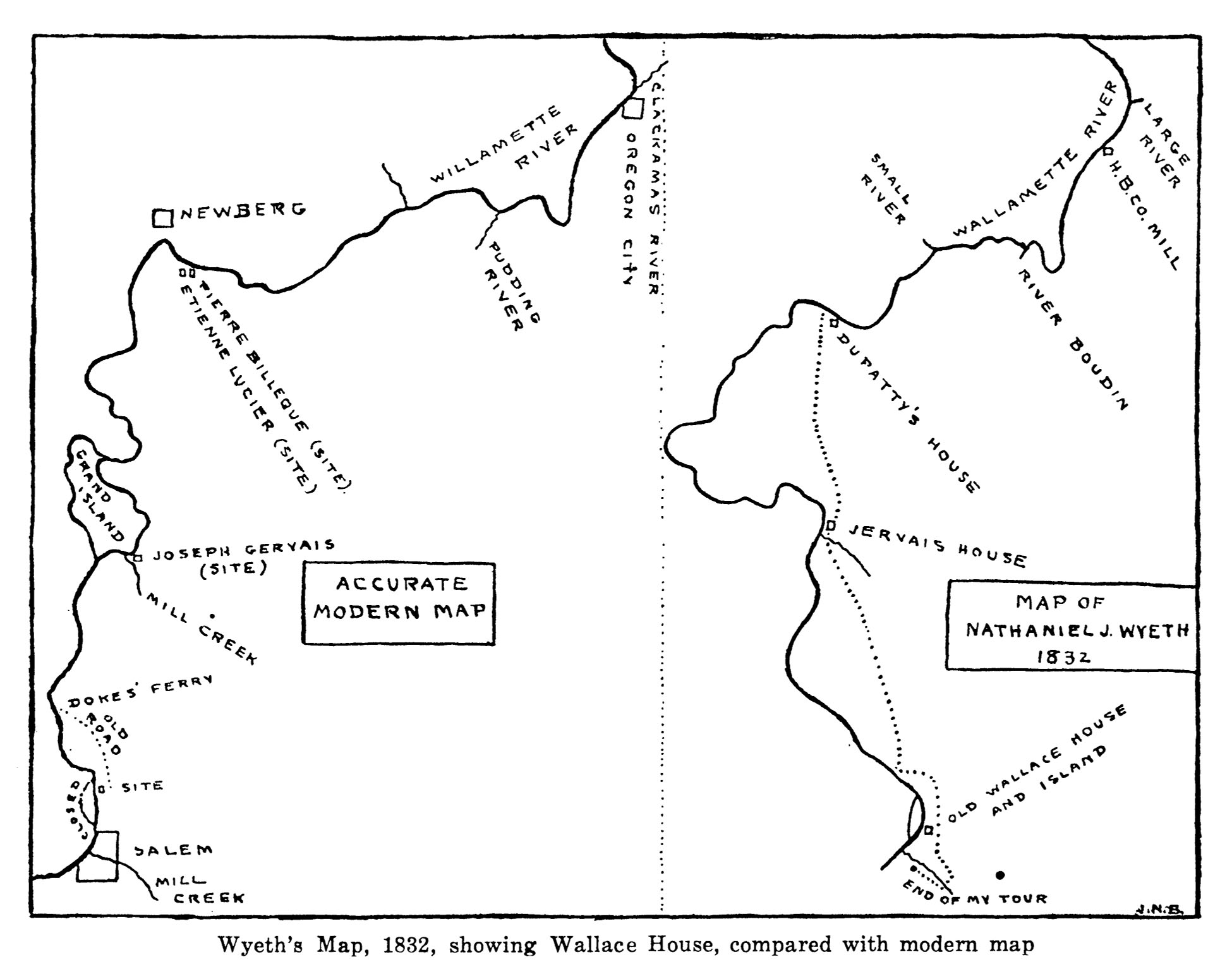

Day resumed his hunting duties through October 1812, often in the company of Thomas McKay, ranging above Tongue Point on the lower Columbia, near the second river named for him in Oregon. In late November, he joined a party led by Pacific Fur Company officers William Wallace and John Halsey to overwinter and trap beaver in the Willamette Valley and establish a post at Wallace House.

He spent the next summer hunting near Astoria and was released from the Pacific Fur Company in October following the sale of the company to the North West Company. Now a free trapper under contract with the North West Company, Day overwintered with a trapping party in the Willamette Valley. On March 20, 1814, he returned to Astoria—now called Fort George—and nine days later arranged to trap the interior basin of present-day southern Idaho and northern Utah, known as the Spanish River area. The historical record then becomes largely silent on Day, though historians presume he was hunting and trapping in the Snake River Country as a freeman for the North West Company.

John Day reappears in 1819 as part of a North West Company expedition into the Snake Country, led by Donald Mackenzie. According to Mackenzie, Day died in a winter camp on February 16, 1820, and was buried there. His grave was a landmark for later fur trappers, and recent research suggests that it lies below Fallert Springs, perhaps along Uncle Ike Creek, a tributary of the Little Lost River. The day before his death, Day allegedly wrote a will that bequeathed his estate to Mackenzie and his family. While the document accurately describes Day’s estate, historians have questioned its legitimacy.

Due more to the resources in the John Day River watershed than to any accomplishments of the man himself, John Day is indelibly linked to Oregon through place-names that include two Oregon rivers, the Grant County cities of John Day and Dayville, north central Oregon’s John Day River Basin, the Columbia River’s John Day Dam, the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, and the John Day Formation rock strata.

-

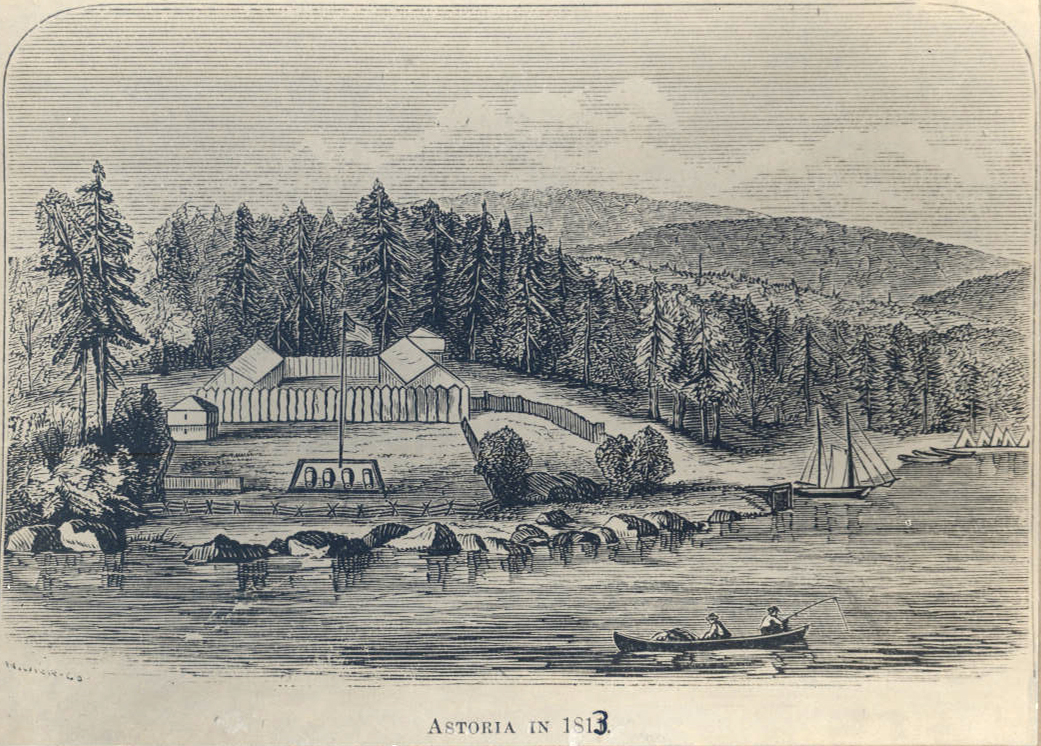

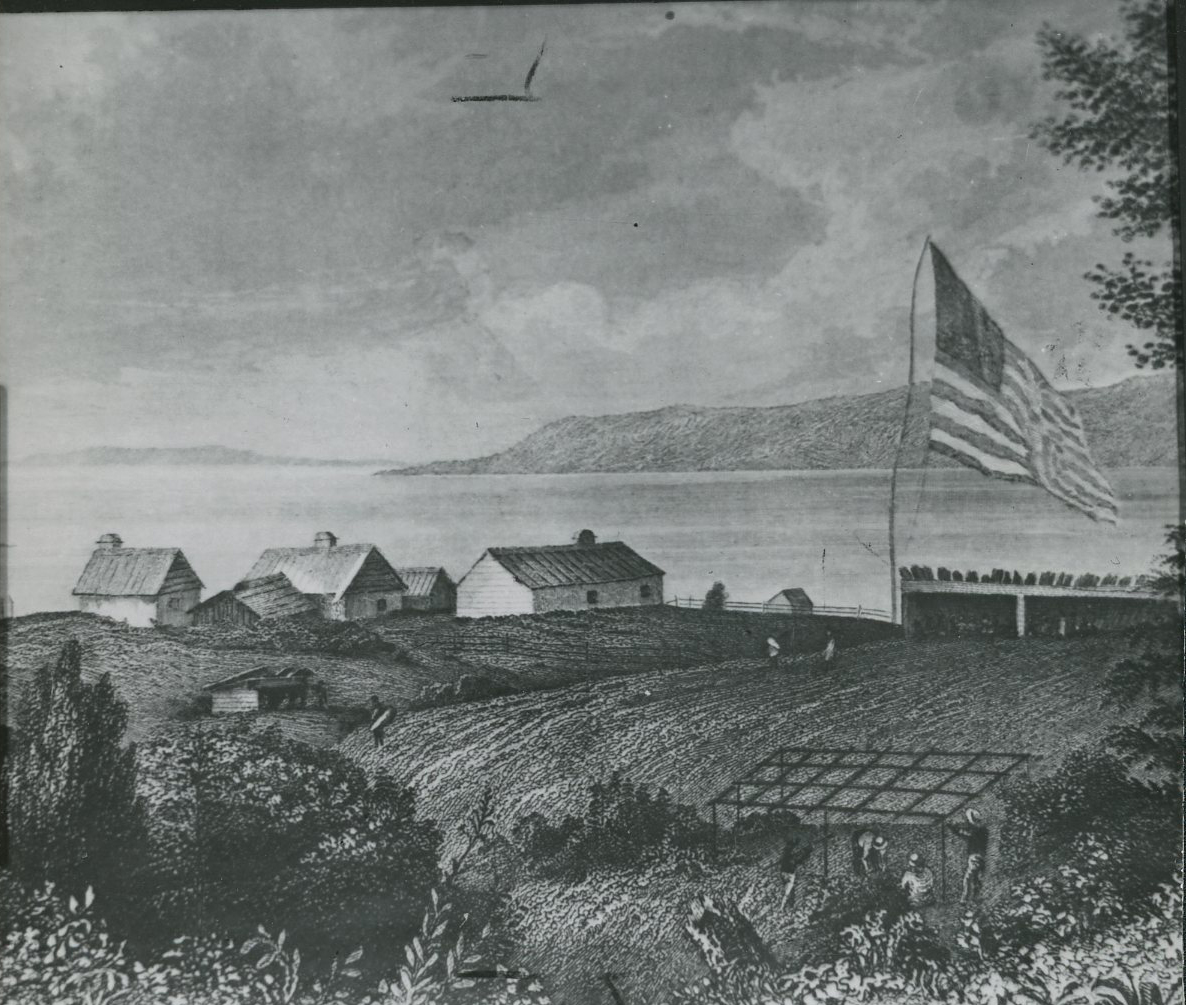

![Earliest known illustration of Fort Astoria, by Gabriel Franchere, employed by Astor,]()

Fort Astoria, 1813.

Earliest known illustration of Fort Astoria, by Gabriel Franchere, employed by Astor, Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi51

-

![]()

John Day River, 2016.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Bob Wick

-

![John Day Fossil Beds]()

John Day Fossil Beds.

John Day Fossil Beds Courtesy Univ. of Oregon Libraries, Gifford Photo Collection, P218 SG607 Series I

-

![Photograph of Painted Hills Unit of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Lava flows of the Columbia River Basalt Group (picture Gorge Basalt) rest on top the colorful beds of the John Day Formation. Photograph by Marli Miller.]()

Painted Hills Unit of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument..

Photograph of Painted Hills Unit of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Lava flows of the Columbia River Basalt Group (picture Gorge Basalt) rest on top the colorful beds of the John Day Formation. Photograph by Marli Miller. Courtesy Marli Miller

-

![John Day dam with fish ladder (John Vincent, photographer)]()

John Day dam with fish ladder (John Vincent, photographer).

John Day dam with fish ladder (John Vincent, photographer) Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi104451

Related Entries

-

![Astor Expedition (1810-1813)]()

Astor Expedition (1810-1813)

The Astor Expedition was a grand, two-pronged mission, involving scores…

-

Astoria (book, 1836)

Although Washington Irving (1783-1859) never traveled to Oregon Country…

-

![Fort George (Fort Astoria)]()

Fort George (Fort Astoria)

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post establi…

-

![John Day River (north-central Oregon)]()

John Day River (north-central Oregon)

The 281-mile-long John Day River in north-central Oregon is the longest…

-

![Pacific Fur Company]()

Pacific Fur Company

The Pacific Fur Company, employee Alexander Ross wrote in 1849, was “an…

-

![Wallace House (trading post)]()

Wallace House (trading post)

Wallace House, built in 1812 north of the Kalapuya village of Chemeketa…

-

![Wilson Price Hunt (1783-1842)]()

Wilson Price Hunt (1783-1842)

In 1809, John Jacob Astor selected Wilson Price Hunt to be his St. Loui…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Drumm, Stella M. “More About Astorians.”Oregon Historical Quarterly, 24.4 (December 1923): 335-360.

Elliott, T.C., ed. “Last Will and Testament of John Day.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 17. 4 (December 1916): 373-79.

Haskins, Devon. "Left naked and afraid: The story behind how John Day River earned its name." What's In a Name? KGW8, Portland. June 14, 2023.

Irving, Washington. Astoria; or Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains, Vol. 1-3. London: Richard Bentley, 1836.

Jones, Robert F., ed. Annals of Astoria: The Headquarters Log of the Pacific Fur Company on the Columbia River, 1811-1813. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999.

Keith, Lloyd and John C. Jackson. The Fur Trade Gamble: North West Company on the Pacific Slope, 1800-1820. Pullman, Wa.: Washington State University Press, 2016.

Ronda, James P. Astoria and Empire. Lincoln, NE.: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

Ross, Alexander. Adventures of the First Settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1849

Spaulding, Kenneth A., ed. On the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart’s Journey of Discovery. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953.