The north-south Oregon–to–California Trail was the main overland route for travel and shipment of goods between the two states during the nineteenth century. The trail, which began as a rough trappers’ route, became a crucial overland link that eventually established the course of a north-south rail line and a modern highway on the West Coast.

Horse-mounted Hudson’s Bay Company fur trappers, operating out of Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River, began using the northernmost section of what became the Oregon–to–California Trail during the 1820s. By the mid-1830s, HBC trapping brigades regularly traveled the full length of the route between the lower Willamette Valley and the Sacramento Valley. Shown on early maps as the “H.B.C. trail,” the route passed through the mountainous interior of southwestern Oregon and northern California. It was a well-used pack trail by the late 1840s, and soon freight wagons and stagecoaches replaced the strings of heavily loaded mules that made their way over Siskiyou Pass.

Mid-nineteenth-century travelers knew the Oregon–to–California Trail by various names. During the 1840s and 1850s, many Oregonians referred to the route as the “old trappers’ trail,” as well as the “H.B.C. trail.” Californians bound for Oregon sometimes called it the “Oregon trail,” while some Oregonians headed south dubbed it the “California trail.” The descriptive “trail [or road] over the Siskiyous” was used historically, but only for the short segment that crossed the trail’s highest point, Siskiyou Pass, between the Rogue River Valley and the Klamath River. The name Siskiyou Trail for the entire Oregon–to–California Trail does not seem to have appeared until California historian Richard Dillon’s 1975 book, The Siskiyou Trail: The Hudson’s Bay Company Route to California.

Early Development

Originating in part from a number of Native footpaths, the development of the Oregon–to–California route occurred in segments, beginning in the 1820s when HBC established a route that followed higher ground through the Willamette Valley to the west to avoid marshy areas near the river. Crossing the height-of-land into the Umpqua River drainage by the mid-1820s, the trail descended Elk Creek to the Umpqua, whose banks provided a gentle path west to the coast while a short distance upriver offered an equally easy path southward to the streams of the main Umpqua Valley.

In the winter and spring of 1827, HBC Chief Trader Peter Skene Ogden and his brigade of trappers blazed the southernmost remainder of the trail in present-day Oregon. After exploring central Oregon and the upper Klamath Basin, they headed west, following the Klamath River for some miles, then turned north, ascending Cottonwood Creek, and crossed Siskiyou Pass to follow Bear Creek to its confluence with the Rogue River. Continuing northward, they eventually reached the Umpqua Valley.

HBC trader Alexander Roderick McLeod, in 1829, headed south into present-day California, after retracing Ogden’s path through the Rogue River Valley and over Siskiyou Pass. He skirted the east side of Black Mountain and entered California’s broad Shasta Valley. Then he pushed south, well into the Mount Shasta area, before caching the brigade’s pelts and retreating north over Siskiyou Pass in the face of a terrible blizzard. The following year, HBC's Michel Laframboise reconnoitered the remaining distance south of Mount Shasta—down the upper Sacramento River into the great expanse of the Sacramento Valley—making the final link in HBC’s route through the mountainous terrain. Laframboise, who would become known as the “Captain of the California Trail,” led subsequent HBC parties into present-day California, including the final HBC cavalcade to use the trail, in 1843.

The Oregon–to–California track saw increased use during the 1830s and early 1840s, including by small parties of American trappers as well as herdsmen driving livestock to non-Native settlements in the Willamette Valley. Former trapper Ewing Young brought a hundred horses north in 1834 as part of the Willamette Cattle Company, and he and his partners drove more than six hundred Mexican cattle to the valley in 1837. Former HBC scout and clerk Thomas McKay, who had been with Ogden in 1827, herded more than three thousand sheep north over Siskiyou Pass in 1840. The following year, U.S. Navy Lt. Charles Wilkes, commanding officer of the United States Exploring Expedition, sent a detachment south from the Columbia River to study the geography along the full length of the trail.

Gold Strikes and the Oregon Trail

Wagons first began using the Oregon portion of the trail in 1846 when the Southern Emigrant Road, also known as the Applegate Trail, opened. Traveling west over the Cascades from the upper Klamath Basin, wagon trains joined the Oregon–to–California route in the southern Bear Creek Valley near present-day Ashland; from there, the Applegate Trail followed the same route to Willamette Valley settlements. Because the old north-south trail had not yet been improved for wagons, the first emigrants encountered an extremely difficult passage down the narrow and steep Canyon Creek to the Umpqua.

Discovery of gold in California sent a flood of Oregonians south. Historian Hubert Bancroft later estimated that three thousand people, almost a third of the Willamette Valley’s white population, made the trip in 1848–1849, most of them on the trail. Others took the Lassen Trail route, which intersected the Applegate Trail. Gold discoveries farther north in 1850–1851—on the Trinity and Scott Rivers, through the lower Klamath River canyon, and on the east side of the Shasta Valley at Yreka—attracted thousands of miners to California’s Klamath Mountains.

Shallow-draft steamboats transported cargo to the mining camps by ascending the Sacramento River as far north as Redding. From there pack trains took food and other supplies to mines in the Klamath region. Some of the mule trains followed HBC’s upper Sacramento Canyon route, while others used the summer-only Trinity River–Scott Valley route that crossed two high passes to reach Yreka. Although a few wagons crossed Siskiyou Pass from the Rogue River Valley to Yreka during 1848–1851, most supplies still arrived by mule trains.

A gold strike in Oregon's Siskiyou Mountains helped bring about the first white settlement of the Rogue River Valley. Claiming land under the Oregon Donation Land Act, Rogue Valley farmers found a ready market for their grain and garden produce among miners on either side of the Oregon-California line. The Native paths that trappers stitched together into the Oregon–to–California Trail had brought steadily increasing conflict between Indigenous residents and aggressive white travelers. In the 1850s, when American miners and farmers arrived by way of the trail to stay, the resulting open warfare culminated in the forced removal of most Native people from southwestern Oregon.

By the mid-1850s, a rough wagon road ascended from Ashland over Siskiyou Pass, down Cottonwood Creek, over the Klamath River, and then to Yreka by way of McLeod’s route around the east base of Black Mountain. At the same time, coming from the south, the earliest wagon road to Yreka used the Trinity River–Scott Valley route, but the Sacramento Canyon route to Yreka soon carried wagon traffic as well. By 1859, the California Stage Company had extended regular stagecoach service from Sacramento through Yreka to Jacksonville. The following year, after the company shipped a number of Concord coaches by steamship from San Francisco to the Columbia River, stage service began to Portland, with stations for overnight accommodations and fresh horses at regular intervals along the way.

In later decades, transportation engineers confirmed the geographic logic of the old HBC Trail’s route. In the 1880s, the first rail link between California and Oregon (later known as the Siskiyou Line) closely followed much of it. Construction of the Pacific Highway/U.S. Route 99 in the early twentieth century followed the route as well, and Interstate 5 does so today.

-

![]()

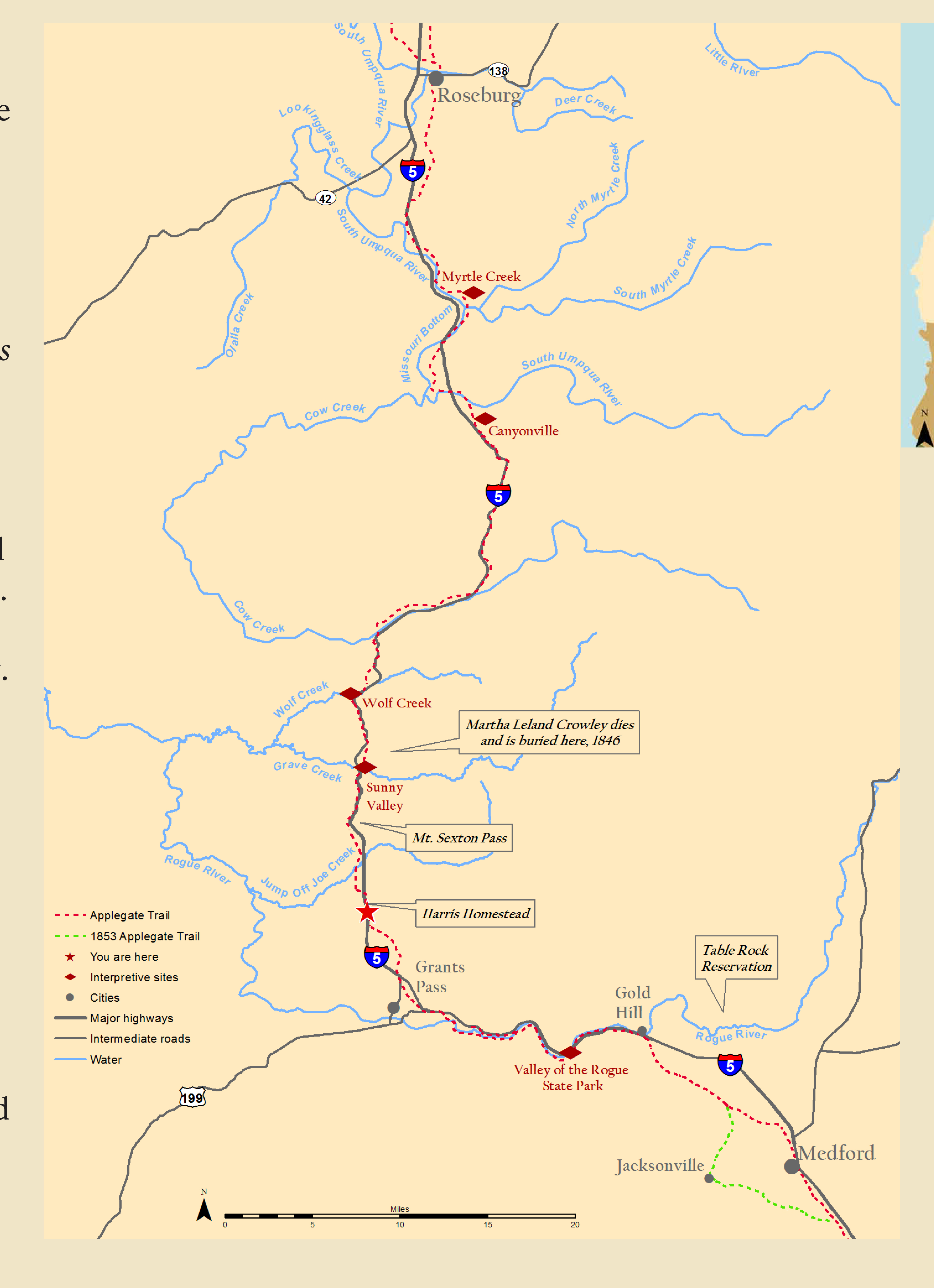

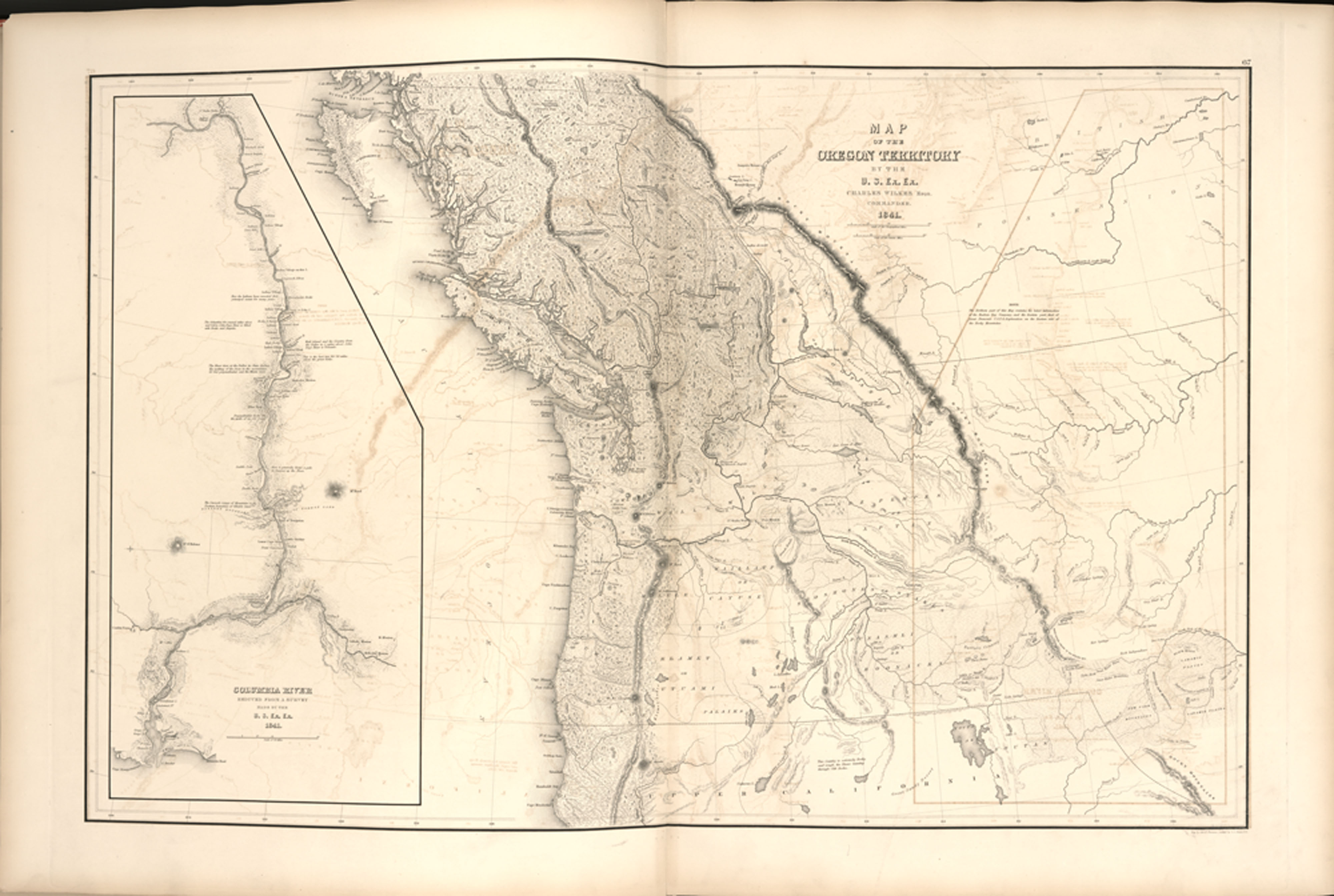

Map of the Oregon-to-California (Siskiyou) Trail.

Courtesy USGS and NorCalHistory

-

![]()

Mount Shasta, c.1867.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Carleton Watkins, Orglot93, Mammoth, 463.

-

![]()

Pacific Highway, Siskiyou Mountains, 1916.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi102420

Related Entries

-

![Applegate Trail]()

Applegate Trail

The Applegate Trail, first laid out and used in 1846, was a southern al…

-

![Council of Table Rock]()

Council of Table Rock

The 1853 Council of Table Rock negotiated a peace treaty between repres…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Interstate 5 in Oregon]()

Interstate 5 in Oregon

Interstate 5 is a 308-mile-long segment of highway that runs between th…

-

![Oregon Trail]()

Oregon Trail

Introduction In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most …

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

-

![Siskiyou Pass]()

Siskiyou Pass

Siskiyou Pass, including the 4,310-foot-high Siskiyou Summit of Interst…

-

![United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842)]()

United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842)

The United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842), also known as the W…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Austin, Ed, and Tom Dill. The Southern Pacific in Oregon. Edmonds, Wash.: Pacific Fast Mail, 1987.

Dillon, Richard. Siskiyou Trail: The Hudson’s Bay Company Route to California. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975.

Munford, Kenneth. The Old Oregon-California Pack Trail. Corvallis,: Oregon State University, 1979.

Munford, Kenneth, and Charlotte L. Wirfs. The Ewing Young Trail. Corvallis: Oregon State University, 1981.

Wells, Harry L.. History of Siskiyou County, California. Oakland: D.J. Stewart & Co., 1881.

Wilson, Dale. “The Oregon-to-California Trail, California Segment; Parts 1, 2, 2 cont’d, and 3.” Western Express: Research Journal of Early Western Mails (June 2002; September 2002; December 2002; June 2003).