As the first state parks superintendent in Oregon, serving from 1929 to 1950, Sam Boardman is often called the father of the state park system. He had a germinal role in building a system that attracted a steadily increasing number of visitors, and he was the catalyst for the state’s extensive land acquisition that often characterizes the face of Oregon to the nation. During Boardman’s tenure, the state park system grew from 4,070 acres in 46 units to 60,000 acres in 161 units.

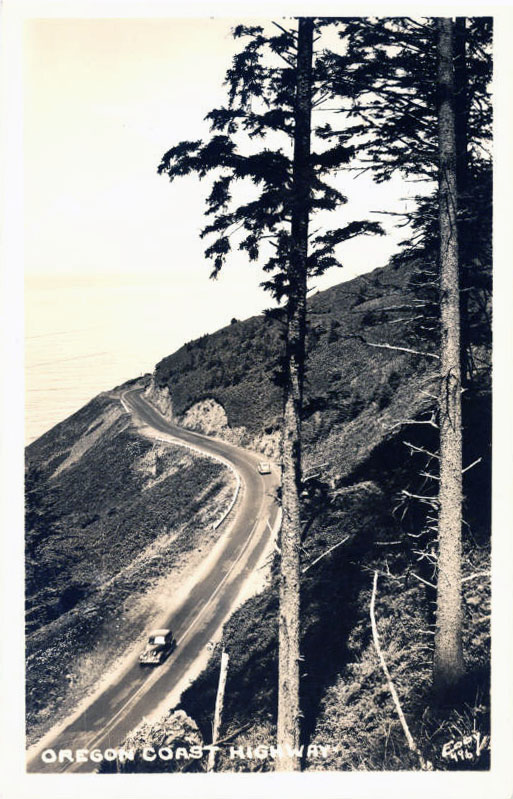

Oregon came relatively late to building its state highway system, starting in 1917, and began to embrace the idea of roadside parks during Governor Ben W. Olcott’s administration (1919-1923). The first parks provided waysides along highways and offered travelers pleasing roadside vistas. With these aims in mind, Oregon made its parks program part of the State Highway Department in 1921. The program remained there until 1989, when the legislature created an independent Oregon Parks and Recreation Department.

Born in Massachusetts on December 13, 1874, Sam Boardman attended public school and spent two years at Wayland Academy in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. He went west as a young man, working as a railroad engineer in Colorado and then homesteading in eastern Oregon’s Morrow County, where he founded the town of Boardman. His efforts at farming the arid land in that part of the state ended in failure. Even as he searched for other work, Boardman promoted local civic improvements, including tree planting and roadside beautification. His wife Anna Belle supported these efforts and taught school; she also helped with the platting of the Boardman town site.

The Oregon State Highway Department hired Boardman in 1919. His work for the department included planting shade trees at highway waysides and being a paving foreman in southern Oregon. Along the way, he acquired considerable knowledge about scenic possibilities along the state’s thoroughfares.

In August 1929, the three-person State Highway Commission hired Boardman to manage and expand the nascent roadside park system. At the time, the system consisted of some small picnic areas, several undeveloped parks, and a few timber reserves that served as reminders to motorists of how highway corridors appeared before industrial logging.

Despite his program’s emphasis on roadsides, Boardman soon began thinking broadly about the prospects for larger and more consequential state parks. He enjoyed considerable latitude in choosing which places might become parks, provided he could garner support from Oregonians and keep acquisition costs low. His first purchase involved a key parcel that became the foundation of Silver Falls State Park.

Boardman’s great challenge involved presenting land acquisition recommendations to the State Highway Commission for funding. He was not always successful, but he did persuade commissioners to add park holdings in the Columbia River Gorge, a precedent for establishing new parks along the Oregon Coast.

Boardman extoled the wild and rugged scenery on the coast as the “creator’s handiwork” and believed that much of the landscape could be preserved in its undeveloped state for the inspiration and edification of future generations. The Pacific shoreline became, under his leadership, the most recognized part of Oregon’s state park system and by 1937 attracted 70 percent of all state park use. Boardman followed no master plan in assembling a system that reflected the best Oregon could offer park visitors—one whose virtues were so obvious that the land must remain in public ownership, yet he could readily defend what amounted to the administrative fiat that created the land bank needed for the use of future Oregonians.

Boardman’s most active period of land acquisition came during the Great Depression, when land prices were low and public dollars were often available. He often conducted negotiations personally, communicating effectively with rural landowners and drawing from his own experiences as a struggling homesteader only a few years earlier. His network of contacts throughout Oregon allowed for frequent communications with owners of key parcels of land who might consider donating or selling their holdings to the state for less than market value.

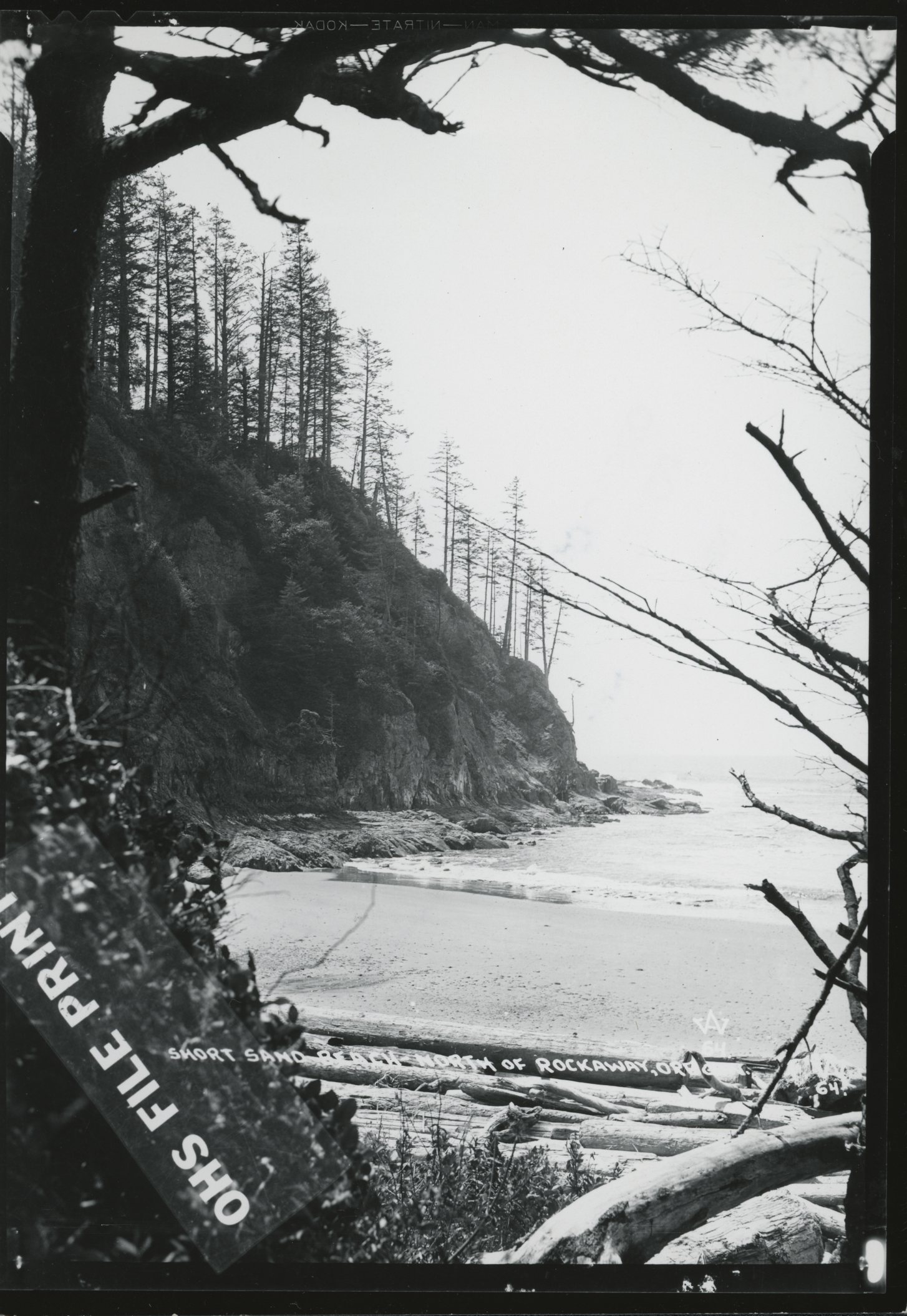

During this period, Boardman began to build keystone parks on the coast, including Ecola, Cape Lookout, Short Sand Beach (named Oswald West State Park in 1958), and Jesse Honeyman. He coordinated Civilian Conservation Corps projects that built trails, picnic shelters, and other facilities. Boardman discouraged campgrounds, large parking lots, and other developments that might compromise the parks’ integrity, mainly because the individual park units were so small.

By 1946, Boardman was working to acquire surplus military lands and defunct lighthouses, in spite of the Highway Commission’s resistance to spending highway funds on park acquisitions. One of his final acts as superintendent was to assemble a spectacular twelve-mile stretch of coastline north of Brookings for a state park that was ultimately named for him.

Boardman retired in 1950 and remained in Salem until his death in 1953. His writing, though largely restricted to correspondence, became best known after his death with the publication of his account of how some of the parks came into existence. Boardman’s park acquisitions garnered him public acclaim, but some of his most ambitious acquisition proposals remain unfulfilled and require renewed efforts to secure them, as he put it, “for all time to come.”

-

![]()

Samuel Boardman, 1950.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 000862

-

![]()

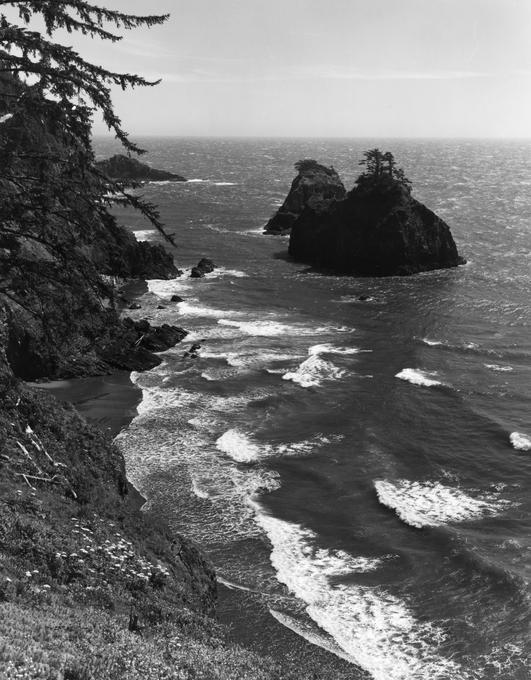

Boardman State Park.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries, g158bh353

Documents

Related Entries

-

![Bates State Park]()

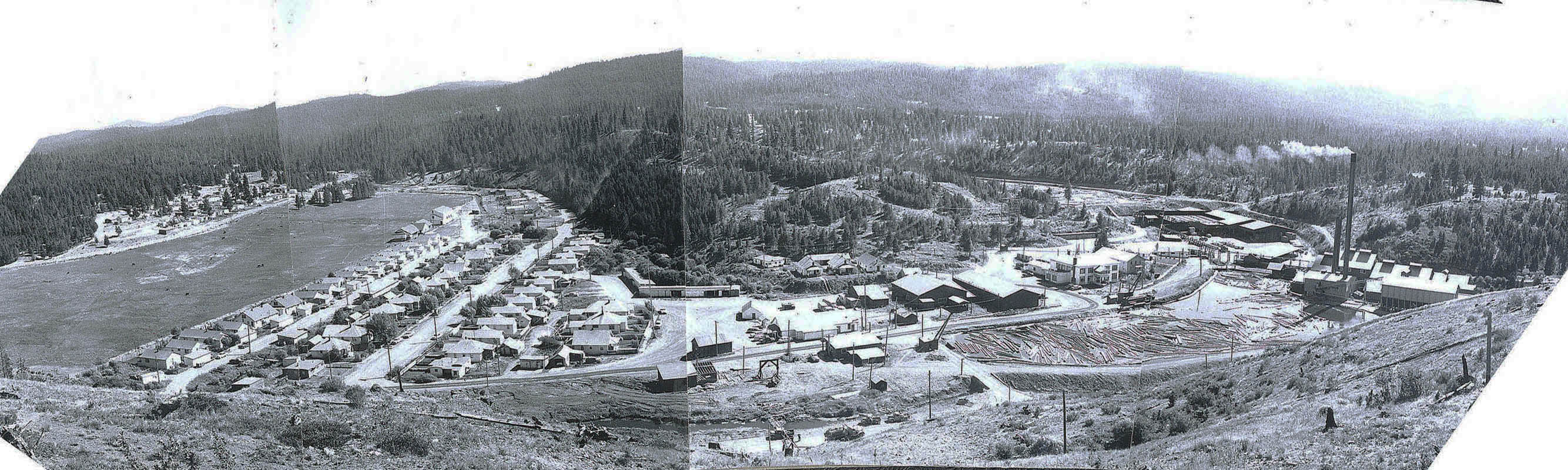

Bates State Park

Bates State Park, located in Grant County, one mile north of Austin Jun…

-

![Boardman]()

Boardman

Boardman, located on the Columbia River in northeastern Oregon, is name…

-

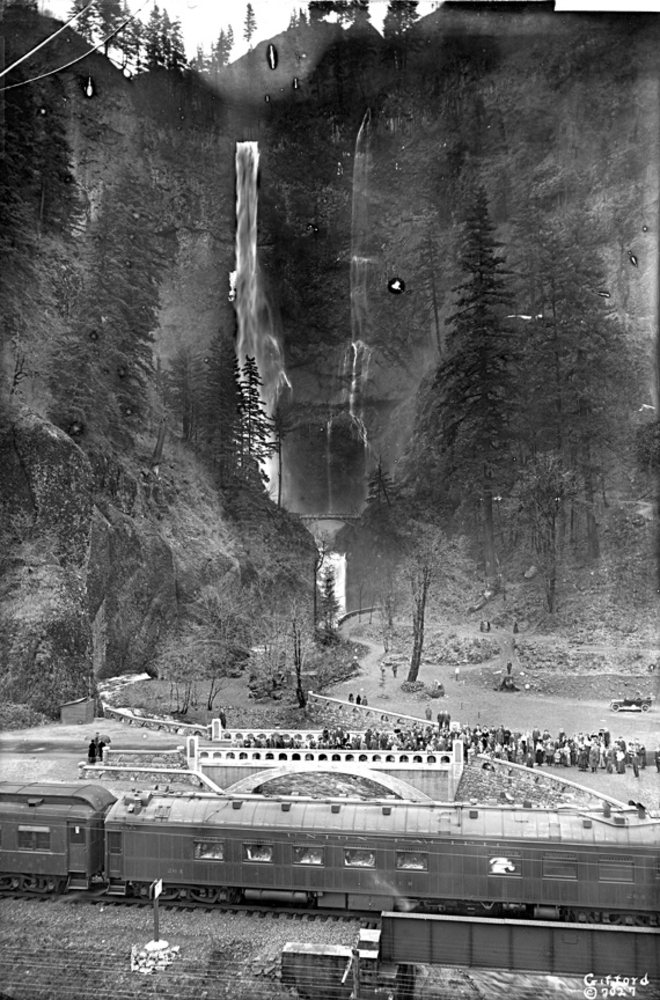

![Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area]()

Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area

Established by Congress in 1986, the Columbia River Gorge National Scen…

-

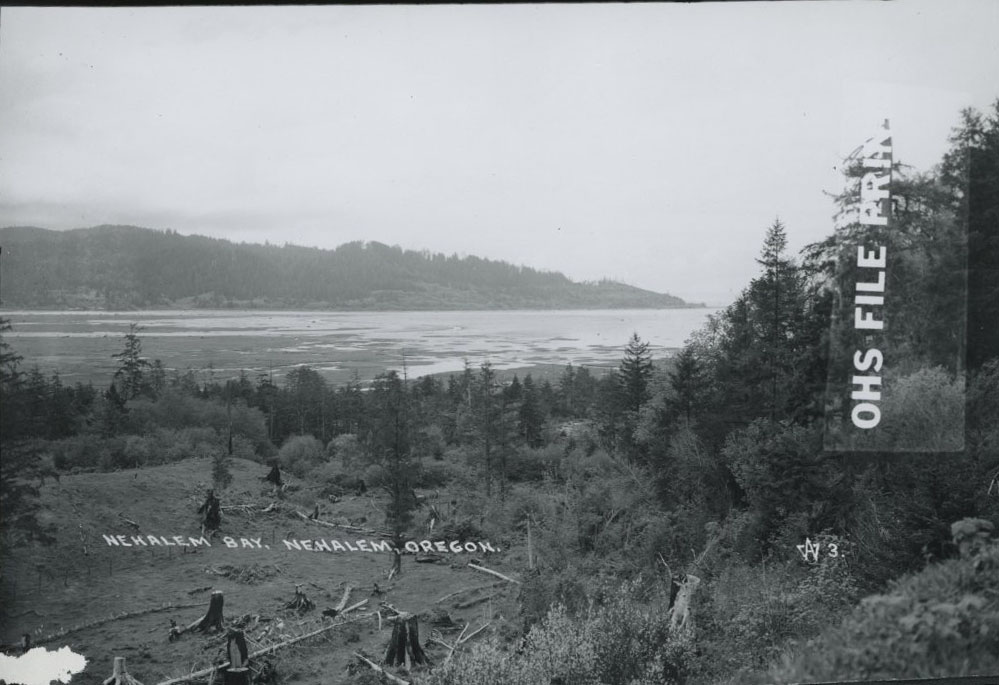

![Nehalem Bay State Park]()

Nehalem Bay State Park

Nehalem Bay State Park occupies almost 900 acres on a sand spit separat…

-

![Oswald West State Park]()

Oswald West State Park

Shortly after Samuel Boardman became Oregon’s first director of state p…

-

![Silver Falls State Park]()

Silver Falls State Park

Silver Falls State Park, located about twenty miles southeast of Salem,…

-

![US 101 (Oregon Coast Highway)]()

US 101 (Oregon Coast Highway)

Many places on the Oregon coast were virtually inaccessible in the earl…

Further Reading

Cox, Thomas R. The Park Builders: A History of State Parks in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Merriam, Lawrence C., Jr., Oregon's Highway Park System, 1921-1989: An Administrative History. Salem: Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, 1992.

Deur, Douglas. "Empires of the Turning Tide: A History of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region." Pacific West Social Science Series, No. 2015-01. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2016.