York was William Clark's slave and an integral member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, sent by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the Louisiana Territory and the Oregon Country in 1804–1806. The written descriptions of York portray him as large, dark, strong, and agile. His date of birth is unknown, but his parents were owned by William Clark's father, and as a young child York had been assigned as the companion and later manservant to Clark. In the traditions of Southern slavery, that usually meant they were of about the same age, which means that York was probably born in about 1770.

Journal entries and oral traditions note that Native people were impressed by York and that his presence operated as a valuable element in the expedition's diplomatic interactions with those they encountered. On October 9, 1804, expedition member Sargeant John Ordway recorded in his journal: "the greatest curiousity to them was York Capt. Clark's Black man. all the nation made a great deal of him." York's contributions also included hunting, medical services, physical labor, and participation in special exploratory activities. During the difficult days of the return trip, when expedition members were near starvation, York was entrusted with the critical task of trading their few remaining valuables with the Natives for desperately needed provisions, ensuring the expedition's survival.

Literary and academic treatments of York subsequent to the expedition downplayed and distorted his indispensable contributions. Negative racial stereotypes used to legitimize Black slavery and oppression were often attached to the York story. In that tradition, he was often cast as a "Sambo" figure, who loved slavery, spoke a heavy dialect, and was obsessed with sex. Conversely, during the Civil Rights era, writers seeking positive role models in a changing racial environment distorted York into a "superhero" who served as guide and interpreter on the expedition and saved Clark's life. Neither depiction is accurate or supported by fact.

Post-expedition accounts tell of York becoming increasingly bitter and resentful, chaffing in his return to the limitations of traditional slave status in Missouri after his liberating experiences in the West. Clark, in response, resorted to the standard arsenal of slave-master controls prevailing in that era. At various times, Clark "trounced" (beat) York, had him jailed, and hired him out to a "sever" master to break his spirit, according to a collection of letters Clark wrote to his older brother. The letters were discovered among Clark family papers in the 1980s and are now contained in Dear Brother, edited by James J. Holmberg.

Clark eventually granted York his freedom in about 1816, approximately ten years after the expedition's return to St. Louis. York's final fate is clouded in mystery. One version, offered by Clark, claims that York grew to hate his freedom and died in Tennessee while trying to return to his old master. Another version, based on a description by an 1830s mountain man named Zenas Leonard, has York living out an honored life as a Crow Indian chief in the West. There is no conclusive evidence to support either version.

-

![Statue of William Clark's slave York, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806. The statue is installed in Louisville, Kentucky.]()

York.

Statue of William Clark's slave York, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-1806. The statue is installed in Louisville, Kentucky. Fair use

-

![]()

York statue at Mount Tabor Park, Portland, April 2021.

Courtesy Tania Hyatt-Evenson

-

![Mural of York, by Richard Haas, Oregon Historical Society, 1989]()

Mural of York, Oregon Historical Society, 1989.

Mural of York, by Richard Haas, Oregon Historical Society, 1989 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., DM 15999001

-

![]()

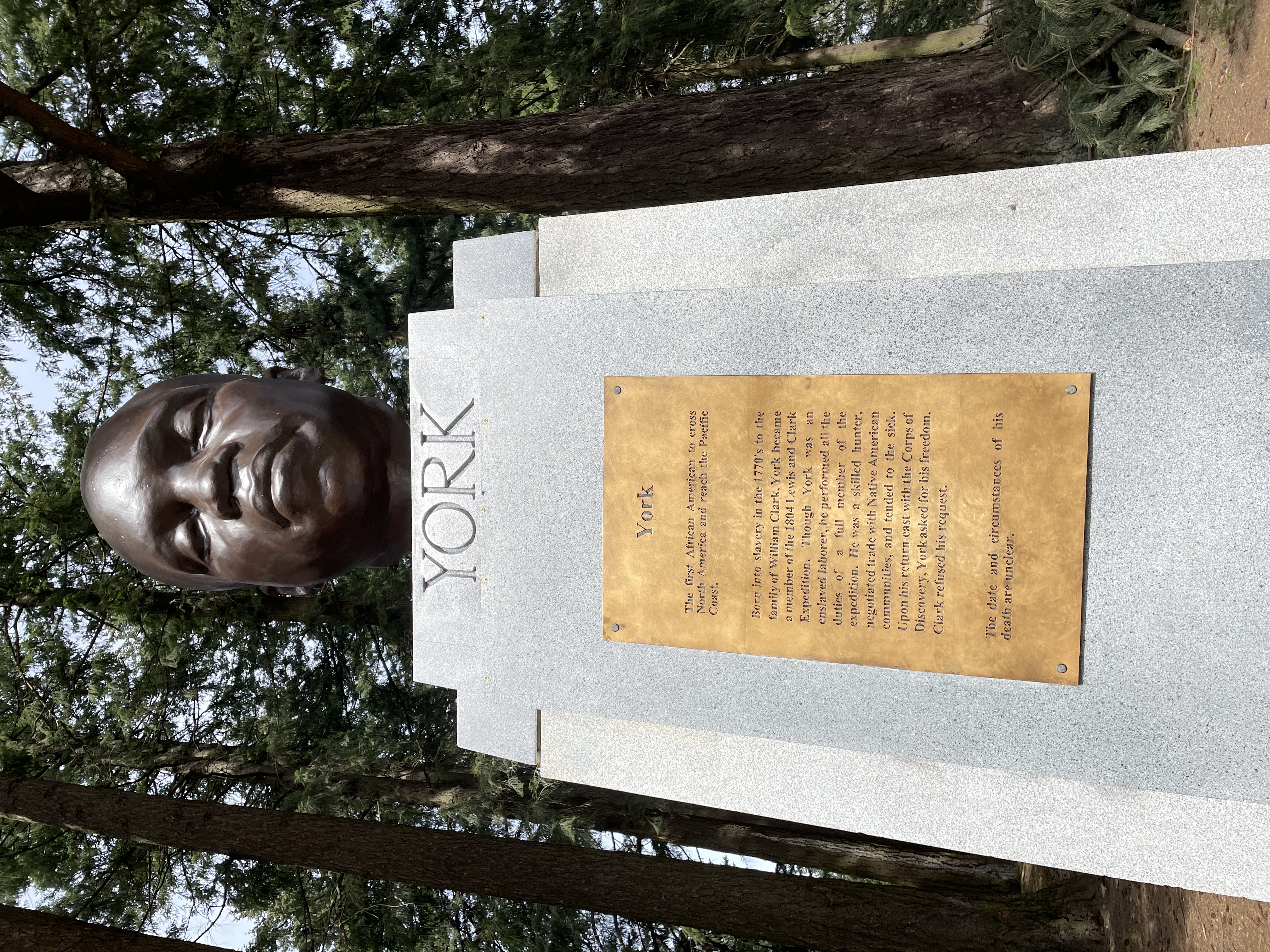

Bust of York, Mount Tabor Park, Portland, April 2021.

Courtesy Tania Hyatt-Evenson

-

![The sculpture was installed by unknown persons in February 2021, on the pedestal which previously supported a statue of Harvey W. Scott.]()

Bust of York by an unknown artist at Mount Tabor Park, Portland, 2021.

The sculpture was installed by unknown persons in February 2021, on the pedestal which previously supported a statue of Harvey W. Scott. Courtesy Tania Hyatt-Evenson

Related Entries

-

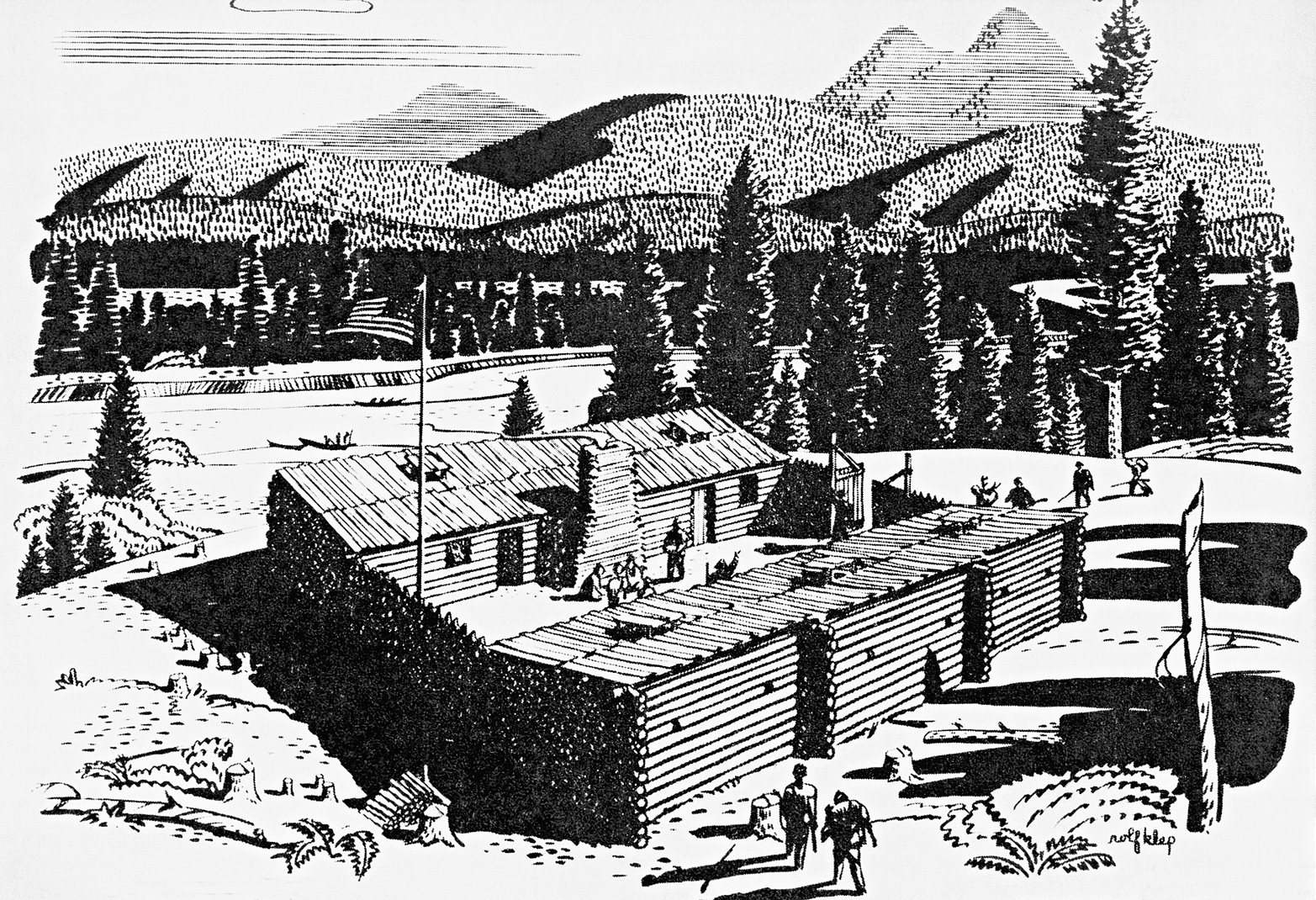

Fort Clatsop

Built in 1805 near present-day Astoria, Fort Clatsop was the winter qua…

-

![Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)]()

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (1805-1866)

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau is remembered primarily as the son of Sacagaw…

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

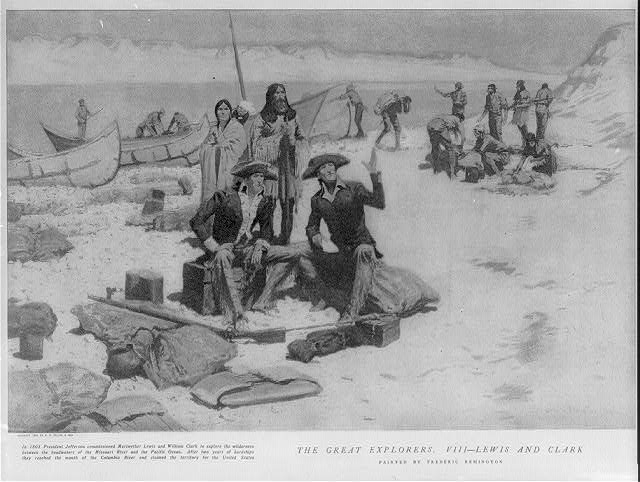

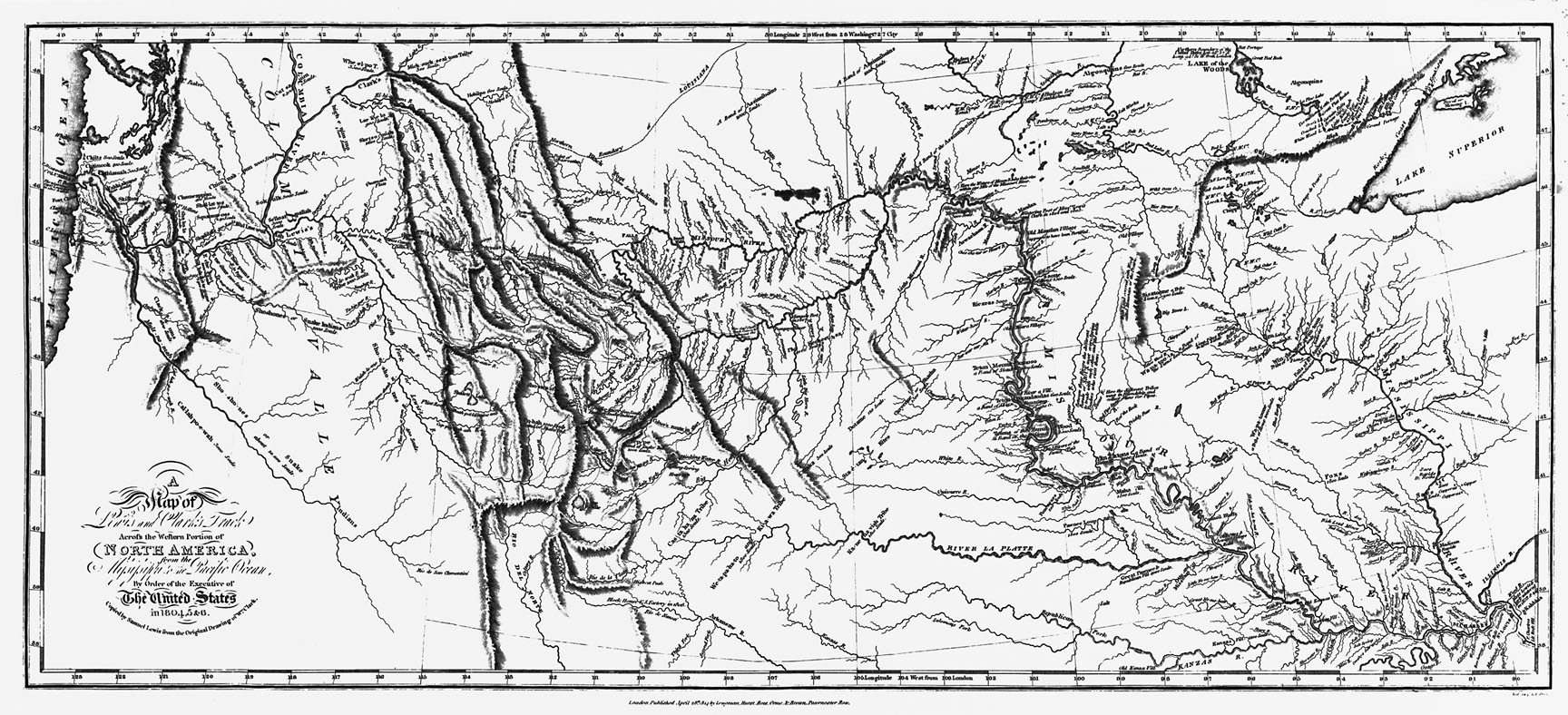

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

![Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809)]()

Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809)

Reflecting on Meriwether Lewis after his death, Thomas Jefferson bemoan…

-

![Patrick Gass (1771-1870)]()

Patrick Gass (1771-1870)

Patrick Gass was one of the early enlistees in the expeditionary force …

-

![Sacagawea]()

Sacagawea

Sacagawea was a member of the Agaideka (Lemhi) Shoshone, who lived in t…

-

![Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- c. 1839-1843)]()

Toussaint Charbonneau (1767- c. 1839-1843)

Toussaint Charbonneau played a brief role in Oregon’s past as par…

-

![William Clark (1770-1838)]()

William Clark (1770-1838)

William Clark is indelibly connected to Oregon in many ways, some obvio…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Betts, Robert. In Search of York, Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2000.

Clark, William. Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark. Louisville, KY: The Filson Historical Society, 2003.

Millner, Darrell M. "York of the Corps of Discovery: Interpretations of York's Character and His Role in the Lewis and Clark Expedition." Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 104, no.3 (Fall 2003): 302-333.

Millner, Darrell M. York of the Corps of Discovery. Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 2004.

Moulton, Gary e., ed. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. 13 vols. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986-1997.