Tejanos (Tay-HAH-nohs)—Mexican Americans from south Texas—began moving to Oregon in significant numbers for seasonal agricultural work during the post-World War II period when farmers experienced labor shortages. While they do not comprise the majority of Oregon’s Latino population, as they did decades ago in the 1950s-1960s, Tejano families who settled in the state helped build networks of community and social service organizations that have served Latino communities for decades.

In Spanish, Tejano means "Texan," and has been used since the nineteenth century to refer to Texans of Mexican descent. The term originally referenced those who settled in Texas prior to statehood, but its current usage is not limited to their direct descendants. While some definitions include people from central Texas or anywhere in Texas, many associate the term specifically with communities in southern Texas near the border with Mexico. Tejano broadly refers to a person belonging to a Mexican American culture that incorporates aspects of dominant American and Texas social influences, such as cooking ingredients (like flour tortillas and yellow cheeses) and musical instruments (playing the accordion differently than in some Mexican regional styles), and is distinct from the cultures of Mexico. Tejanos who permanently left Texas brought Tejano culture with them and actively practiced it in their new communities.

During WWII, the shortage of male agricultural laborers due to military service led the United States to formalize an immigration and labor agreement with Mexico. The Bracero Program, funded in part by the federal government, recruited men from Mexico to travel to the U.S. and work on farms and railroads in 24 states, including Oregon. After the war, changes to the program shifted the costs of transporting workers to farm owners, who avoided paying those costs by recruiting another source of inexpensive labor: working-class Tejanos.

In the 1950s and 1960s, farm owners worked with contractors and recruiters to spread the word in Texas about opportunities available in Oregon. At the time, Tejanos faced intense discrimination in Texas, as well as depressed wages and scarce work options, and many migrated with their entire families. The logistics of family life made seasonal migration difficult. By settling permanently, people could keep their children in the same school system and avoid the social and financial costs of constantly relocating. The lack of a sales tax and a relatively mild climate also made Oregon enticing. The number of Tejano families who chose to settle permanently increased significantly during the 1960s.

From Hillsboro in Washington County to Independence in Polk County to Ontario and Nyssa in Malheur County, Tejanos settled in communities where agricultural work was available. In Malheur County, Japanese American farm owners offered Tejanos employment picking crops, working in packing houses, and eventually as labor contractors and migrant camp managers. Japanese American farmers, who had experienced discrimination and (for many) incarceration during WWII, were generally sympathetic to the Tejanos and tended to treat them with more respect than most white farmers did. Prejudice and discrimination from the white population in Oregon was generally less overt than in Texas, however, and families found white allies. For many of the families, girls and women worked alongside boys and men to make ends meet, disrupting traditional gender norms for labor. Tejana women took on community leadership roles and pursued non-domestic work opportunities.

In many Oregon towns, Tejanos were the first Latinos to settle permanently in significant numbers. The desire for familiar cuisine, cultural institutions, and other Spanish speakers encouraged families to work together and support each other. In Independence, the Tejano community established the Spanish American Organization in 1966 to advocate for their interests, host events, and provide resources for migrant workers. Tejanos actively practiced a unique culture that differed from those of Mexican nationals. In the 1960s and 1970s, for example, many Tejanos preferred baseball over soccer, and dances typically featured their distinctive conjunto music.

In the 1960s and the 1970s, the Chicano Movement provided the impetus for Tejanos and other Mexican Americans in Oregon to expand their support networks for education, healthcare, vocational training, and other needs. Cultural centers, such as Centro Cultural de Washington County and Centro Chicano Cultural between Woodburn and Gervais, were formed to provide Spanish-language services and host community events. Tejana women were central to those efforts.

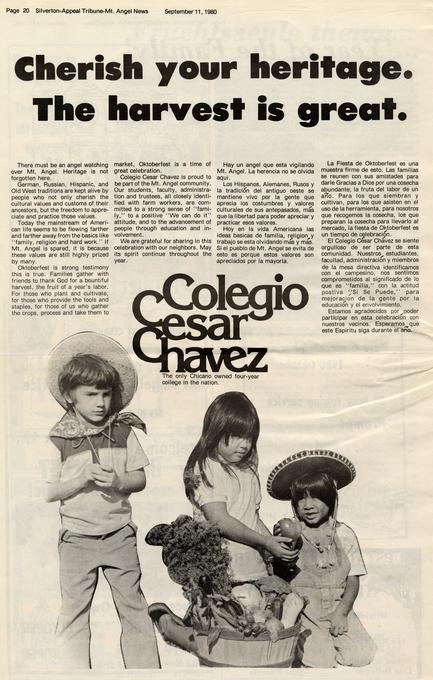

Celedonio “Sonny” Montes, who arrived in Oregon from Texas in the 1960s, was instrumental in shaping multiple institutions to benefit Latinos and migrant workers. After working at the Valley Migrant League, Montes was hired at Mt. Angel College in 1971 to recruit Mexican American students. When Mt. Angel was on the verge of closing, Montes and others persuaded the board to rename the college Colegio César Chávez and enroll primarily Mexican American students. Many Tejanos earned degrees and found employment there before financial problems forced the college to shut down in 1983. A number of former employees, including Montes, pursued long careers in education in Oregon and created programs to benefit Latinos and other students.

After 1970, the Latino population grew rapidly, with much of this growth due to the arrival of Mexican nationals. The Latino population grew from 32,000 in 1970 to 65,000 in 1980, and to 112,707 in 1990. In multiple Oregon communities, there was tension between new Mexican immigrants and established Tejano communities, caused in part by cultural differences and conflicts between Tejano camp supervisors and Mexican laborers.

Those tensions, however, have not prevented Tejanos and other Latinos from working together to build an inclusive community. One enduring example of their efforts is the establishment of the Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center, a medical clinic formed by members of Washington County’s Centro Cultural in collaboration with St. Vincent Hospital and Tuality Community Hospital to provide care for migrant families and other Spanish speakers. Today, the health center provides care for thousands of Latinos and non-Latinos, serving patients who speak over 60 languages. As the Latino population in Oregon has grown, new and lifelong residents have relied on many such foundational community and social service networks built by Tejanos.

-

![Every year, the Cavasos family travels from Texas to Oregon for seasonal farm work.]()

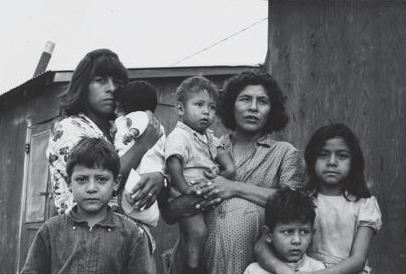

Maria Cavasos and her family at a migrant labor camp, October 7, 1966.

Every year, the Cavasos family travels from Texas to Oregon for seasonal farm work. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Digital Collections, Valley Migrant League photographs, Org. Lot 74, Box 1, Folder 6, 001 -

![A group of children sit on wooden boards in the back of a bus that transported them and their families from Texas to Oregon for work.]()

Children of migrant laborers sit on wooden boards in a bus in the Willamette Valley, Oregon, July 8, 1966.

A group of children sit on wooden boards in the back of a bus that transported them and their families from Texas to Oregon for work. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Digital Collections, Valley Migrant League photographs, Org. Lot 74, Box 2, Folder 6, 006 -

![The Valley Migrant League's Opportunity Center. From the VML Collection.]()

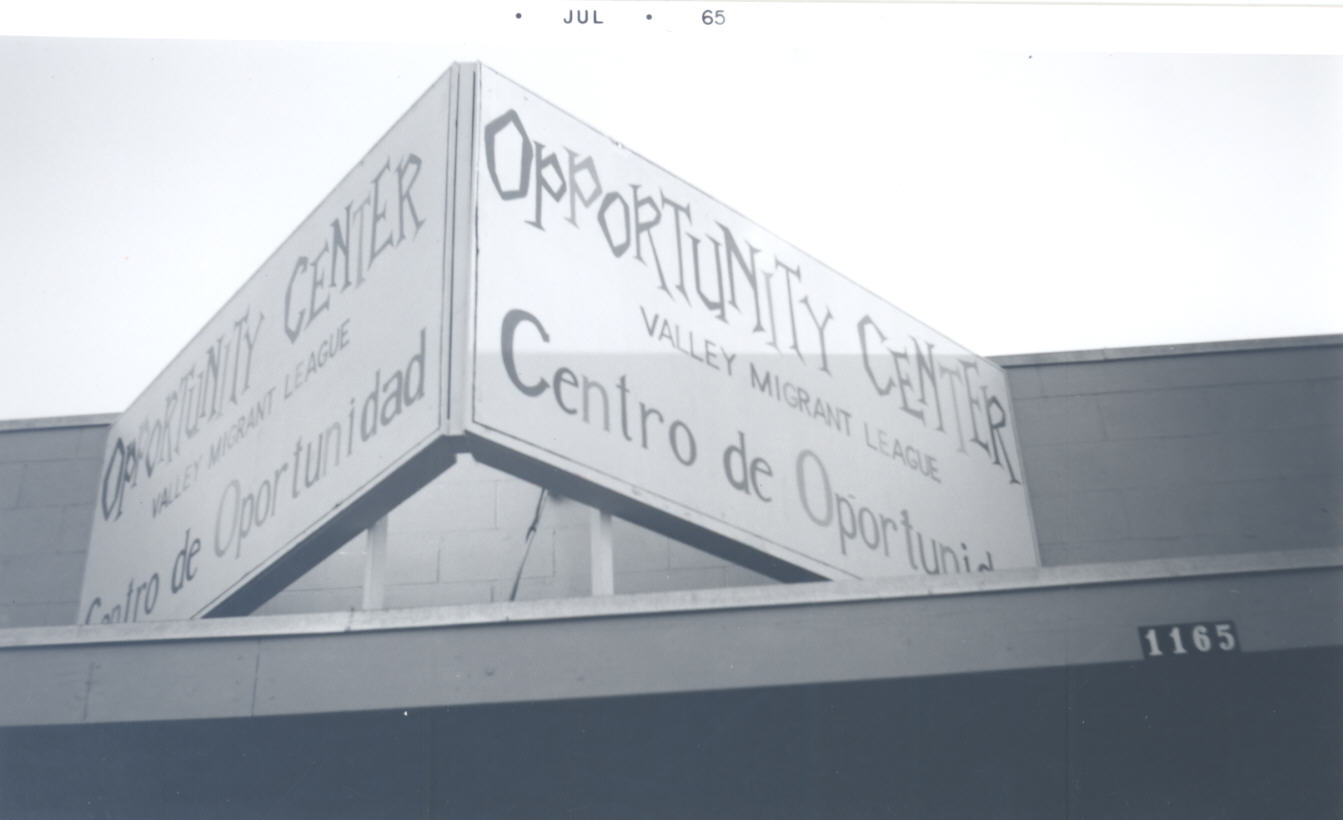

The Valley Migrant League's Opportunity Center.

The Valley Migrant League's Opportunity Center. From the VML Collection. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![]()

A child is immunized at a Valley Migrant League health clinic..

Oregon Historical Society Research Library bb004074

-

![]()

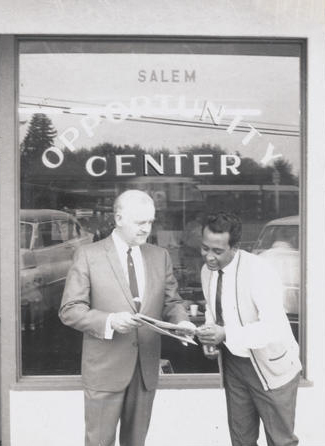

Quentin Rowland and Sam Hernandez stand outside of the Salem Opportunity Center in Salem, Oregon, May 13, 1966.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Digital Collections, Valley Migrant League photographs, Org. Lot 74, Box 1, Folder 1, 011 -

![]()

Ad for Colegio César Chávez, Silverton-Appeal Tribune, September 1980.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries

-

![]()

Colegio César Chávez catalog.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries

Related Entries

-

![Bracero Program]()

Bracero Program

The Mexican Farm Labor Program, also known as the Bracero Program, was …

-

![Centro Cultural de Washington County]()

Centro Cultural de Washington County

Centro Cultural de Washington County is an educational and cultural cen…

-

![Colegio César Chávez]()

Colegio César Chávez

Colegio César Chávez, located in Mt. Angel in the lower Willamette Vall…

-

![Latinos in Oregon]()

Latinos in Oregon

The arrival of Latinos in Oregon began with Spanish explorations in the…

-

![Valley Migrant League]()

Valley Migrant League

From 1965 until 1974, the Valley Migrant League (VML) helped Oregon mig…

-

![Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center]()

Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center

The Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center was established in 1975 to p…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Sifuentez, Mario Jimenez. Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2016.

Sprunger, Luke. “‘This is Where We Want to Stay’: Tejanos and Latino Community Building in Washington County.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 116.3 (2015): 278–309.

Ochoa, Victor Daniel. Somos De Allá y de Aquí: Tejano Soujourners, Mexican Immigrants, & the Creation of a Familiar Mexican Place in Independence, Oregon 1950 – 2000. Master of Arts thesis, University of Oregon, 2024.