Sterlingville was a mining boomtown at the headwaters of Sterling Creek, about seven miles south of what is now Jacksonville, Oregon. The town was named for James Sterling, who left Illinois in his mid-twenties with his mother and two younger siblings to cross the plains to Oregon Territory in 1853. Sterling took a Donation Land Claim in Eden Precinct (today's Phoenix, Oregon) and farmed it in partnership with Aaron Davis, a 19-year-old Iowan. The two men had arrived in Jackson County soon after the discovery of gold, and like many farmers at the time, decided to become part-time prospectors. The following year, their own discovery of gold gave rise to the bustling town of Sterlingville—one of several boomtowns that seemed to suddenly appear during the gold rush—eventually leading to one of the largest hydraulic mining operations in Oregon.

The area is on the homelands of the Upland Takelma (Latgawa) and the Dakubetede peoples, who had been resisting white encroachment of their lands since the 1830s. Some of the confrontations were violent, and the federal government sent agents to southern Oregon to negotiate land seizures and the removal of Native people to reservations. Native leaders signed treaties in 1853, but what had become the Rogue River War raged on. White settlers and miners continued to make land and mining claims throughout this period of unrest, and many joined volunteer army units. By 1856, most of the Native population in the area had been captured and forcibly removed to reservations.

The history of Sterlingville begins when Sterling and Davis staked a mining claim near Jacksonville in the fall of 1853. The following spring, they discovered that their claim had been “jumped,” or taken over by other miners, during the winter. In these early territorial times, miners formed mining districts in order to adopt rules and practices to govern competition for claims. It was generally accepted that claims could be held only by those who stayed to work them fulltime; but in some districts, farmer-miners were “excused" from April to October to attend to their farms. Sterling and Davis fell into that category of miners, but they did not benefit from the exception in their district, so they lost their claim. The men took a circuitous route from Jacksonville back to their farm, through the Applegate watershed. They prospected during a stop for lunch, discovered gold on a tributary to Little Applegate Creek, and determined to return.

In June 1854, with three additional men to help explore the stream, Sterling and Davis realized they had found an extensive source of gold and returned to Eden Precinct for a good supply of provisions and tools. They pledged to keep the location of their bonanza a secret, but by the time Sterling returned the creek had been "staked out and occupied by a horde of bustling miners for its full length from bank to bank." Davis had reserved a half-claim for Sterling, but the standard share of a discoverer was at least a double claim. Sterling angrily rejected the offer and returned to his farm.

The gold strike attracted miners and merchants eager to supply them, and a small town formed halfway between the mouth and source of the creek, which residents called Sterlingville—also known as Sterling City, Sterlingtown, or Sterling—after the absent original claimant. By the early fall of 1854, more than a thousand people lived in the town, which included a saloon, stores, hotels, boardinghouses, a bakery, and a butcher shop. The Jackson County Court named a constable, delineated the Sterling election precinct, and appointed Uriah Seabury Hayden as justice of the peace on July 10, 1854. The town site was platted in 1855.

The exceptionally dry winter of 1855–1856 led many miners to abandon their claims. Downstream miners dug a ditch to bring water from the Little Applegate River to the dry bed of Sterling Creek, but the project was abandoned when the returns were too meager. A wet spring gave hope that Sterlingville would prosper, but the winter of 1857 disappointed. Mining shafts undermined the abandoned buildings. In 1860 the census recorded 123 residents and at least thirty buildings were unoccupied, and few commercial businesses remained. According to one account, by 1870 "the buildings of the once promising town had largely disappeared. Those still standing were empty derelicts." Farmers and ranchers began to take over the Sterling Creek watershed. They mined after the hay was cut and the crops were in, leaving productive gravel beds and veins dormant when it was time to plow the fields in the spring or harvest in the fall.

During the 1870s, technological advances in hydraulic mining released the wealth still hiding along Sterling Creek, but the town did not revive. Powerbrokers U. S. Hayden and Theodric Cameron consolidated claims and sold them to Portland capitalists. The Sterling Mine Company built a 26-mile water ditch in just six months (June to November 1877), relying on hundreds of Chinese laborers. The enterprise was led by David P. Thompson, former Territorial Governor of Idaho. By 1879, multiple hydraulic giants were being used to mine gold by blasting away the creek’s banks and boulders, and the company was acquired by Captain Alexander Postlewaite Ankeny in exchange for the block in downtown Portland on which Ankeny had built the lavish New Market Theater.

The two hundred people still living in the watershed of Sterling Creek were granted a post office in 1879, which postmaster George Yaudes called "Sterlingville"; but the office closed four years later. Henry Ankeny, who acquired Sterling Mine upon his father's death in 1891, built a house for his family at the old town site, but no new community arose. The schoolhouse was moved miles away in the 1920s, and squatters lived along the banks of Sterling Creek during the Depression until they were evicted when Quercus Corporation leased the mine in 1934. Large-scale mining on Sterling Creek was over by World War II, and the town was no more.

Rural residential properties have been built on the former footprint of Sterlingville, and the Sterling Mine ditch has been developed as a 41-mile multi-use trail system by the Siskiyou Upland Trails Association and U.S. Bureau of Land Management. The Sterlingville Cemetery, where the earliest marked grave is that of Susan Ida Smith who died in 1863, is maintained by the Sterlingville and McKee Bridge Historical Societies.

-

![]()

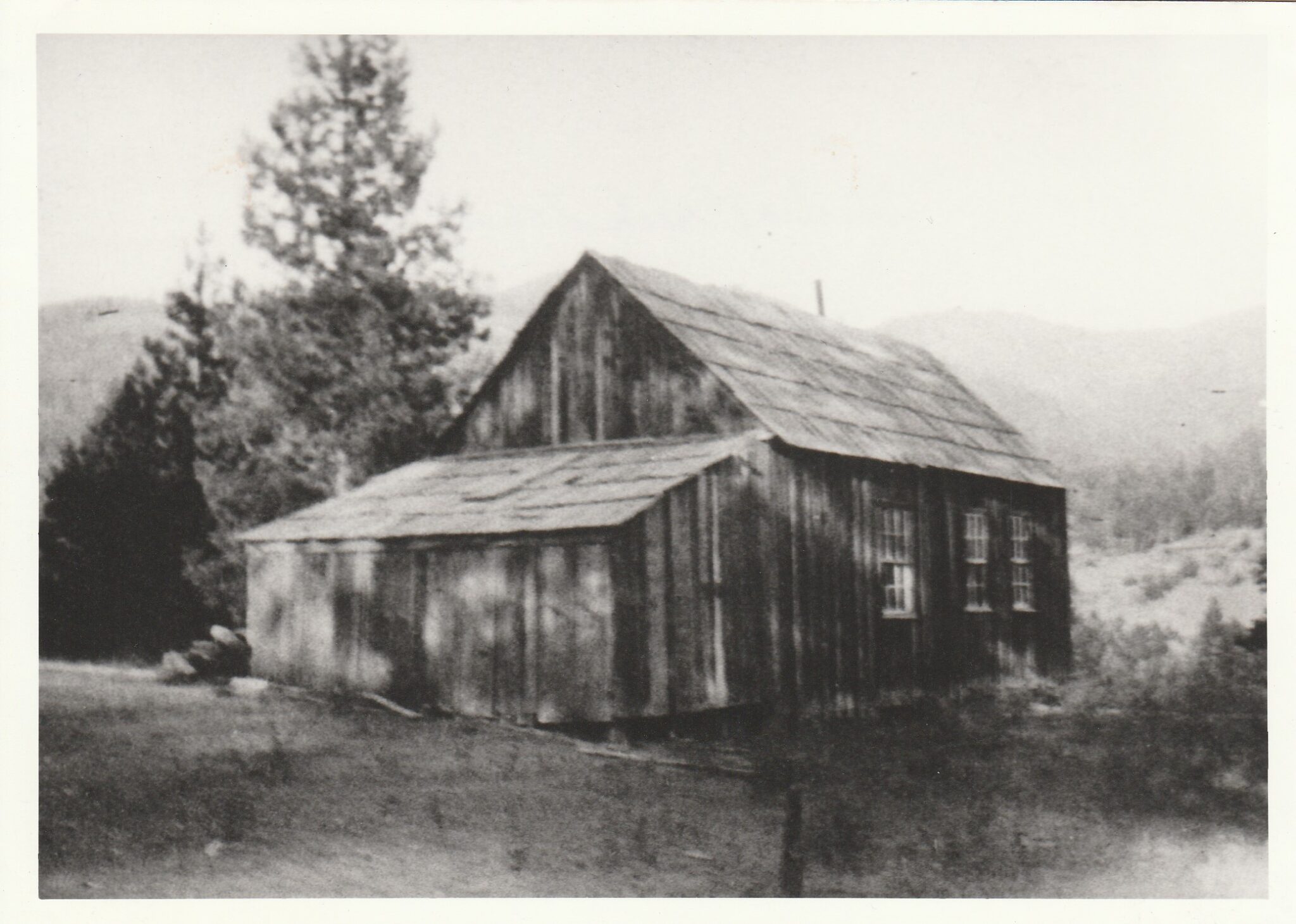

Ankeny family home, 1891.

Courtesy McKee Bridge Historical Society, Evelyn Byrne Williams Collection, 0400 -

![The schoolhouse was destroyed by fire in 1918.]()

Sterling Creek schoolhouse, 1917.

The schoolhouse was destroyed by fire in 1918. Courtesy McKee Bridge Historical Society, 0533.1 -

![]()

-

![]()

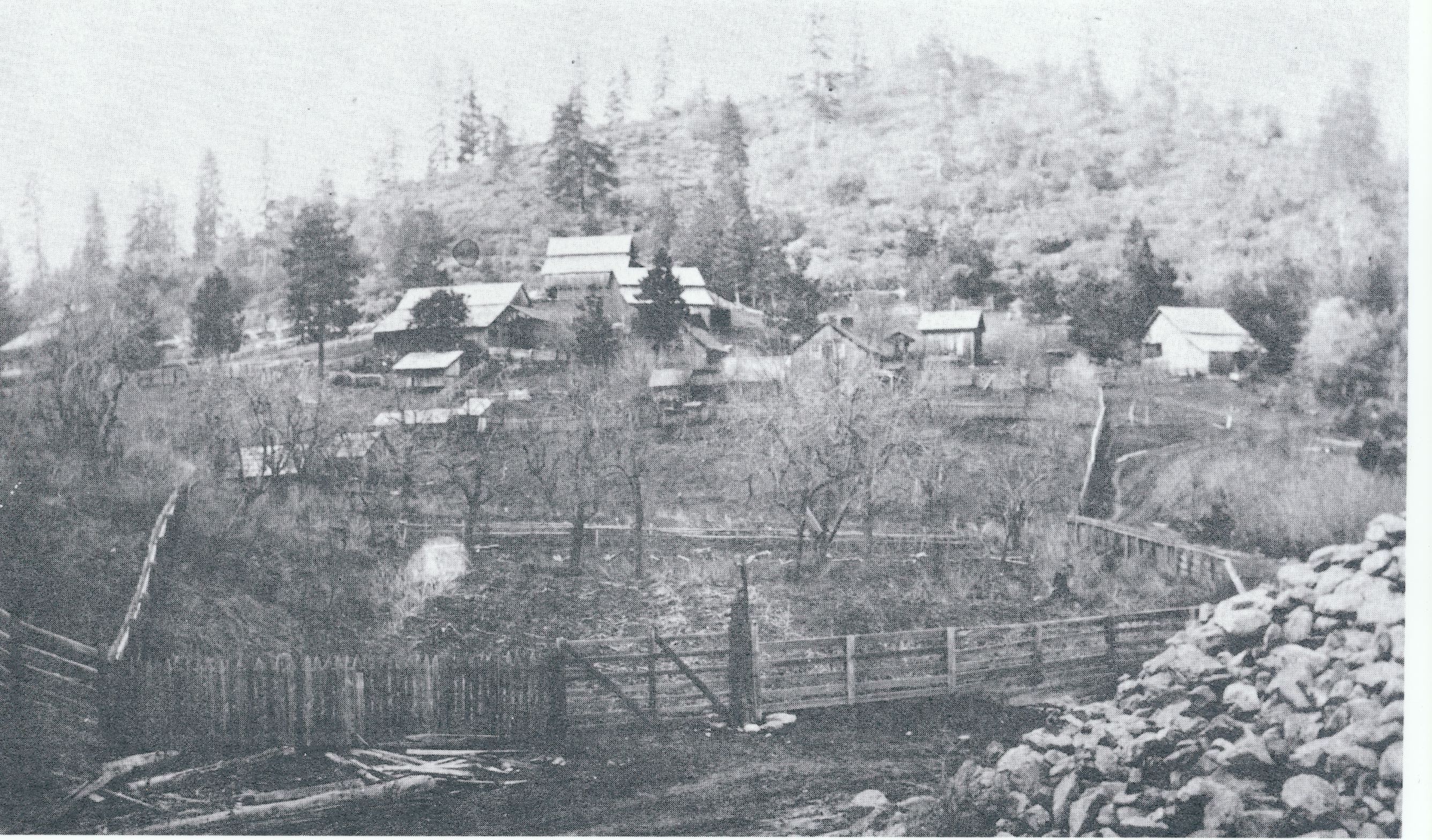

1857 survey of Sterlingville by Sewell Truax.

Courtesy McKee Bridge Historical Society, General Land Office records, 1014 -

![]()

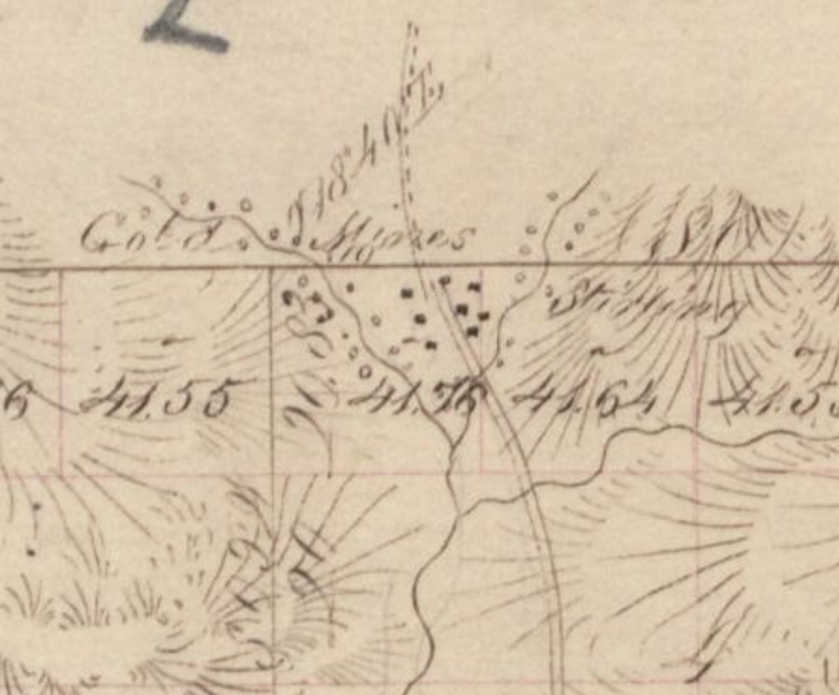

James Sterling.

Courtesy E. Grifford

-

![]()

Hydraulic mining at Sterling Mine.

Courtesty Southern Oregon Historical Society, 005086 -

![]()

Sterling Creek schoolchildren, 1917-18.

Courtesy McKee Bridge Historical Society, 0551.1 -

![]()

Sterling Hydraulic Mine Operation, Jackson County.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Oregon Journal Collection, OrHi 65160

-

![Yaudes was a merchant-miner. He was buried beside his three children who died of diphtheria within a 12-hour span in 1884.]()

George Yaudes plot at Sterlingville Cemetery.

Yaudes was a merchant-miner. He was buried beside his three children who died of diphtheria within a 12-hour span in 1884. Courtesy Laura Ahearn

-

![]()

George Yaudes grave marker after repair by McKee Bridge Historical Society.

Courtesy Laura Ahearn

Related Entries

-

![Applegate River]()

Applegate River

The approximately sixty-mile-long Applegate River is one of three north…

-

![Buncom]()

Buncom

Buncom (also Bunkum, Buncombe or Buncomville) is situated at the conflu…

-

![Chinese mining in Oregon]()

Chinese mining in Oregon

The city of Guangzhou (formerly known to Westerners as Canton) is the c…

-

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

-

![Table Rock Treaty of 1853]()

Table Rock Treaty of 1853

The Council of Table Rock brought a temporary peace between Indigenous …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Haines, Francis D., Jr. “Sunrise to Sunset at Sterlingville.” Table Rock Sentinel, March 1982,

Siskiyou Upland Trails Association.

Sterling Creek-Sterlingville. McKee Bridge Historical Society.