Quinaby (Quimby, Quiniby), a Tsimikiti (Chemeketa) Kalapuya Indian, saw the first whites settle in French Prairie in the mid-Willamette Valley. Known as Chief Quinaby to resettlers in Salem, he reportedly carried himself in a regal manner and was considered an honest person who worked to keep peace between Indians and whites. The Kalapuyans in the Willamette Valley were never known to have committed any act of war against invading resettlers, even when they were being treated unfairly and were removed from the valley. To many people in Salem, Quinaby represented the last of the Kalapuya people, and he was hosted as a celebrity until his death.

Quinaby’s father was Chemeketa, and his mother was from a Chemawa village. The Tsimikiti lived between Mill and Pringle Creeks in present-day Marion County, an area that was the traditional territory of the Santiam Kalapuya—one of the most powerful tribes in the Willamette Valley. Before Salem was established, Kalapuya people visited the Tsimikiti area to harvest camas in the vast prairies there. Most of the Kalapuya people died from malaria during the epidemic that raged in the region from the 1830s to the 1840s.

The Kalapuya signed the Willamette Valley Treaty with the United States government in 1855. The next year, Quinaby and the Tsimikiti who had survived the epidemics were removed to the Grand Ronde Reservation, where they were part of the three hundred Santiams who lived at Grand Ronde.

Despite treaty annuities that were designed to support residents of reservations, the people at Grand Ronde were treated poorly by the government and had to fish and hunt in the Coast Range while waiting for food shipments, which did not come often. There were few opportunities for tribal people to work for wages at Grand Ronde, and many temporarily left the reservation and visited nearby towns to work. Native people did not become American citizens until 1924 and were not allowed to leave the reservations without permission. Quinaby and his wife Eliza often received travel passes to visit Salem.

In Salem, the couple lived in a dwelling Quinaby built in the brush near the Salem Railroad Depot. At night, he often played Stick Game, a Native gambling game, likely with other Native people who were also traveling in the valley. On one occasion, Daniel Waldo, a prominent white pioneer who had settled Waldo Hills in Salem, confronted Quinaby about the loud noise the players were making during the games. Quinaby responded by saying that he was the last of his people and that this had been his peoples’ land long before whites came. Waldo then left him alone.

Quinaby spoke Chinuk Wawa (Chinook Jargon) in a friendly manner to all he met and often asked for muck-a-muck (food). He did not work regularly, as chiefs who lived a traditional life considered such work to be undignified. Still, Quinaby was known to saw and buck firewood for money and food and to perform menial jobs for households in Salem. He promoted his status as the last of his people—even though several hundred Kalapuya lived on the Grand Ronde Reservation—which brought him sympathy and goodwill in the city. Many Oregon towns had a Native person who was considered the last member of a tribe, and he or she was often hosted and tolerated by local residents who believed they had displaced Native people unfairly.

On July 4, 1875, Quinaby and Eliza reportedly “dressed in the National emblem—the Stars and Stripes,” which they draped over their shoulders and proudly paraded through town. While many Native people during this period wanted to become American citizens and chose to exhibit their patriotism in order to be accepted by local non-Natives, they generally were treated as outsiders. Quinaby served as the “last of the Kalapuya” and dressed in regalia (similar to Chief Yelkas in Molalla) at Salem parades, fairs, and national holiday events. Native people from all the reservations, including Quinaby, commonly attended the state fair.

Quinaby died in Salem during Christmas week 1883. Eliza continued to visit Salem into her eighties, but it is not known when she died or if they had children. Quinaby was buried under the old oak tree on the grounds of the Bush Elementary School before the school was built (1936). The burial site has never been found, but a plaque was placed on the tree dedicated to Quinaby. The plaque was taken down when the tree and school were torn down in 2005 to make way for a new building of the Salem Hospital. In about 1912, a small town north of Salem was named Quinaby in his honor.

-

![]()

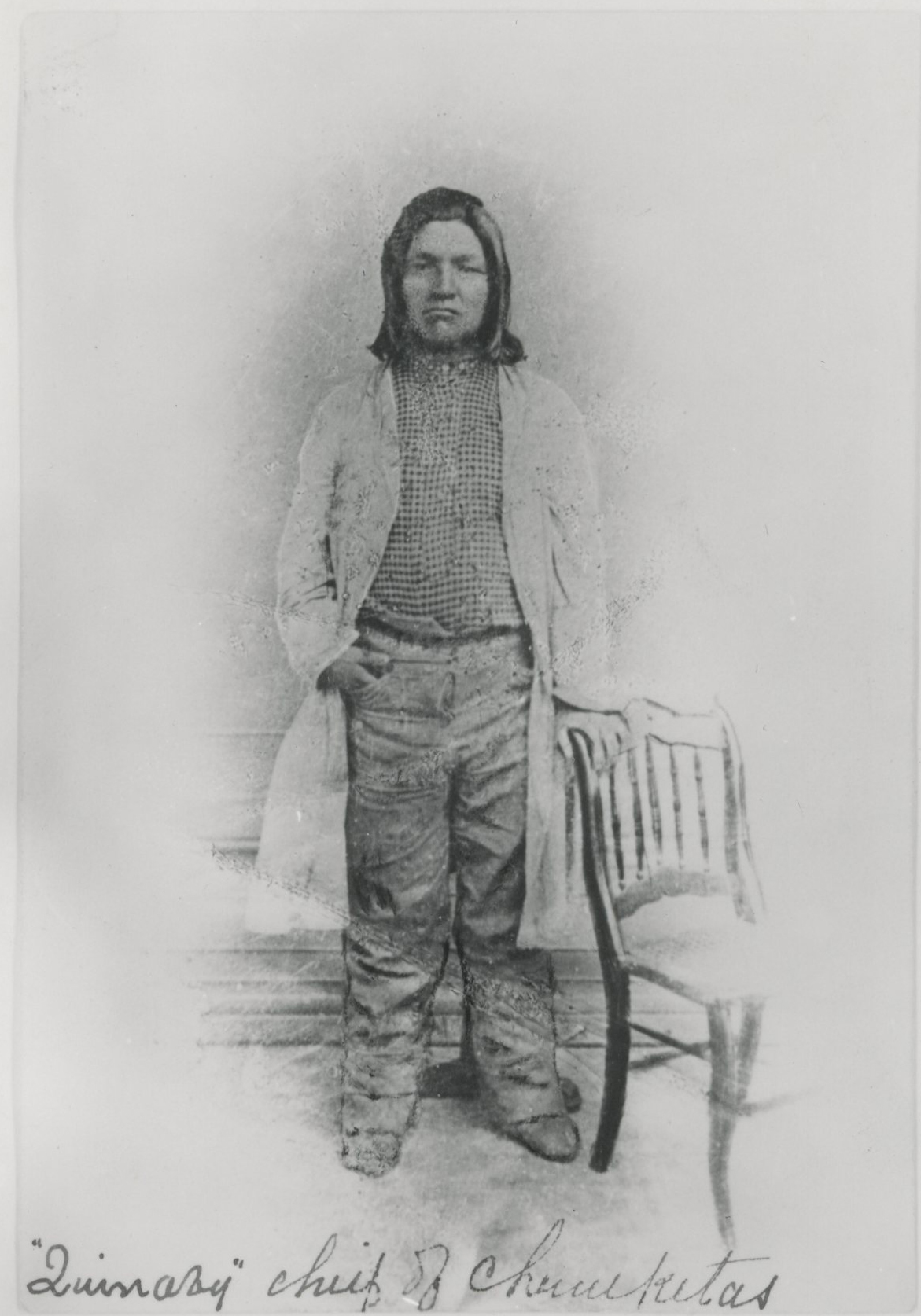

A sketch of Chief Quinaby, c.1870.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi76207

-

![]()

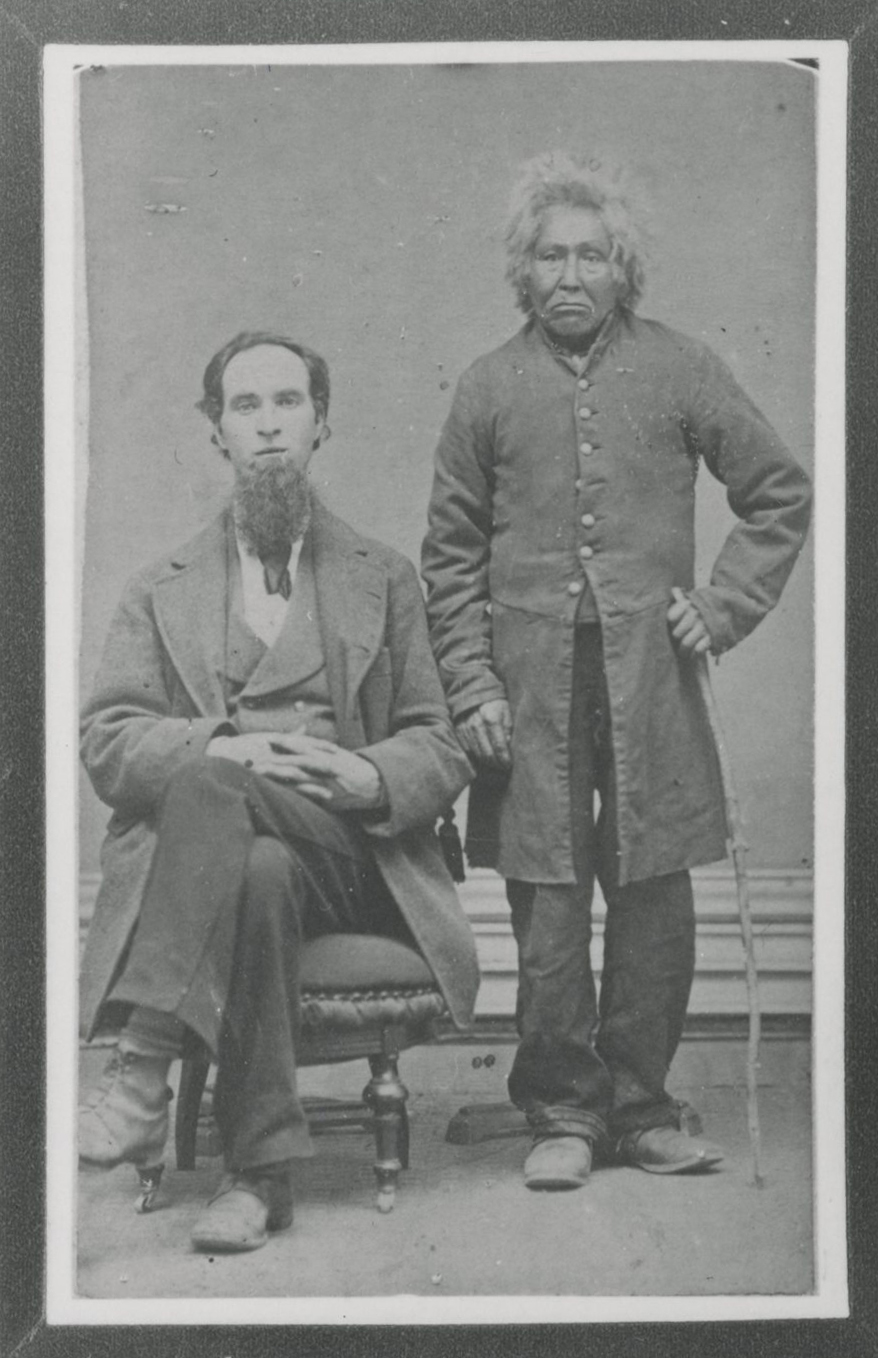

Chief Quinaby (standing) with unidentified man.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi76203

-

![]()

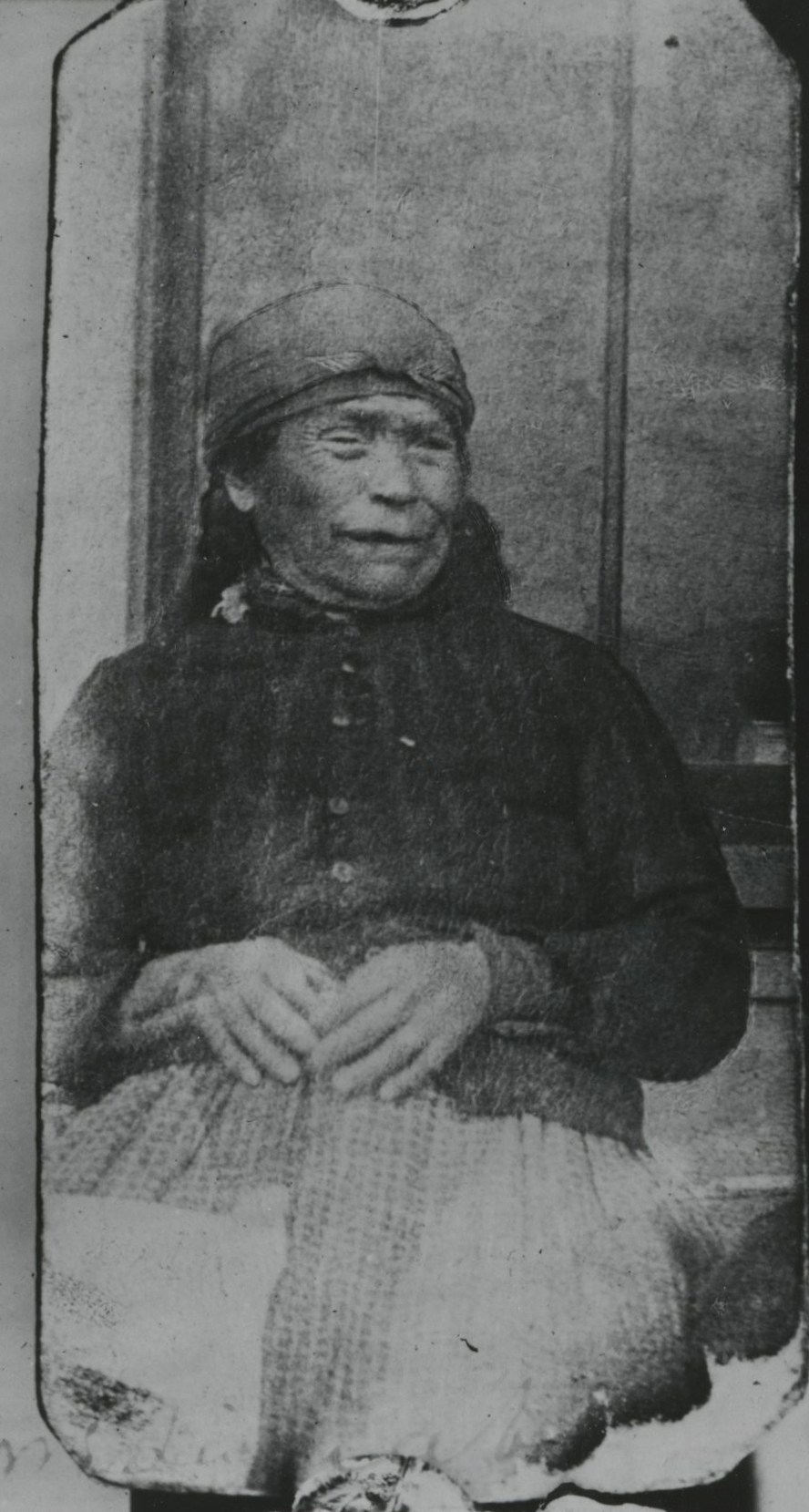

Eliza Quinaby.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019321

Related Entries

-

![Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)]()

Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)

According to our best information, the name "Chinook" (pronounced with …

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![French Prairie]()

French Prairie

Located in Oregon's mid-Willamette Valley, French Prairie was resettled…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Brown, Henry. "The Last of his Tribe: Quinaby." Marion County History xiii (1977-78): 30. (Pamphlet)

“The Story of Quinaby.” Ladd and Bush Quarterly 1.1 (July 1912): 5-7.

“Anecdotes of Quinaby.” Ladd and Bush Quarterly 2.2 (April 1914): 17-21.