It is to Peter Kenoyer (Kinai [kʼiˈnɑ:i]) and his son Louis Kenoyer (Bakhawadas [bɑχɑˈwɑ:dɑs]) that we owe most of what has been preserved of the language and traditions of the Tualatin Kalapuyans, the Indigenous villagers who at the time of first EuroAmerican settlement occupied Tualatin Plains, Wapato Lake (modern Gaston), Chehalem Valley, and adjoining parts of the Yamhill River drainage. The linguistic data and cultural descriptions provided by these two men are especially valuable, considering how rapidly western Oregon Indigenous languages and lifeways gave way to the hegemony of English and EuroAmerican settler culture during the second half of the nineteenth century.

As a young man in 1856, Kinai was among the surviving Tualatins uprooted from their ancestral lands and relocated to the Grand Ronde Reservation, newly established by the U.S. government to segregate and contain the Indigenous peoples of interior western Oregon. By then, the Tualatins had suffered catastrophic demographic declines, the result primarily of introduced diseases. Following in the footsteps of his father, a village chief, and his uncle, the Tualatin treaty chief Kayakach [kʼɑˈjɑ:kʼɑtʃ], Kinai became a prominent spokesman for the people of Grand Ronde, serving as an elected representative and lawyer in the reservation’s self-governing assembly.

Visiting Grand Ronde in 1871, Felix R. Brunot, chairman of a special Board of Indian Commissioners formed to investigate Indian grievances, noted that all Grand Ronde Indians “dress[ed] as the whites,” lived in houses not “wigwams,” and worked just as hard as, if not harder than, their EuroAmerican farmer neighbors. Speaking to the assembled community, Commissioner Brunot commended the people of Grand Ronde for their rapid progress in acquiring the material trappings of EuroAmerican civilization. He also chided them for their lack of progress in other respects, noting their reputed fondness for gambling and whiskey and pointing to their continued adherence to “tamani[w]us” (for Chinuk Wawa Tamanawas [tʼəˈmɑnəwɑs], referring to the power conferred by spirits, the basis of the local Indigenous religion).

Kinai, speaking in English as one of the community’s prominent men, delivered a response whose nuances are interesting to contemplate. As for dressing “as the whites,” he said, “I want Mr. Brunot to know that when he sees us dressed up that we bought the clothes ourselves.” As for gambling, first he denies being a gambler at all, but then revises that image: “we get off the side of the road, where no good men see us, and we gamble, but when a good man comes along we are ashamed of it. So it is with the white man when he does what he knows is wrong.” While he and his entire family are Catholic, he admits that “we go to a tamani[w]us doctor and do many things that we ought not to”—only pointing out that “we do not teach our children these things.” The balance of the speech is devoted to a list of community needs—the apportioning of the reservation’s farmland; a sawmill and a grist mill; farm implements; a carpenter, a blacksmith, and a miller; better schooling for the children.

As this and the other speeches reproduced in the commission’s report reveal, the main concern of Kinai and the other leading men of Grand Ronde was with the survival and economic viability of their reservation community. Grand Ronde Indians of Kinai’s generation saw little choice but to adopt the material and work culture of their EuroAmerican neighbors, among whom were families that had been employing local Indians as farm and domestic workers well before the reservation was created.

Kinai himself had acquired English in the course of long contact with local EuroAmericans, had accepted Catholicism, and had seen to it that his children attended school. At the same time, he spoke Tualatin at home—while using English and Chinuk Wawa outside the home—and he evinced many traits of traditional practice and belief, including a healthy respect for the powers of the reservation's Tamanawas doctors. We know these things because he shared a good deal of his language and traditional culture with U.S. government linguist Albert S. Gatschet, who spent the last two months of 1877 documenting the reservation’s Indigenous languages and traditions, with a special focus on Tualatin. Internal evidence in Gatschet’s field notebooks points to Kinai as the source of most of the Tualatin texts published by Melville Jacobs in part three of his Kalapuya Texts, excluding a creation myth and three versions of a folktale appearing there.

We owe the final form of these texts as published to Kinai’s son, Bakhawadas, who collaborated with academically trained scholars to improve the phonetic accuracy of Gatschet’s texts, made at a time when the study of North American Indigenous languages was still in its infancy. Bakhawadas had spent much of his youth attending the reservation’s schools, initially by day and then as an enrolled student at the Grand Ronde boarding school, established under government auspices and administered and taught by Catholic sisters. In 1885, he left Grand Ronde to be part of one of the first cohorts of Indian students at Chemawa Indian School in Salem. Kinai died in 1886 while his son was away at school.

Bakhawadas’s life following his return to Grand Ronde presents a sobering study in the realities of reservation life. He married and had two sons, both of whom fell ill and died in the same week. His second wife and two adoptive children also died, followed not long after by his mother, Nancy Kenoyer Apperson Tipton Pratt (her first three surnames signifying three husbands whom she had outlived). By 1914, he had left Grand Ronde, thereafter living mostly at Yakama Reservation in Washington. From what little we know about his later life, he appears to have struggled periodically with poverty and alcoholism, no doubt not the future his progressively minded father had envisaged in encouraging him to pursue a formal education. In that light, it is not a little ironic that Bakhawadas’s greatest contribution to posterity should turn out to be the crucial role he played in preserving and enlarging the record of his father’s Indigenous language and culture.

That role commenced in 1915, when Leo J. Frachtenberg, a linguist with the Smithsonian Office of Anthropology, located him at the Yakama Reservation. Frachtenberg read back Gatschet’s earlier transcriptions of Tualatin words and phrases for Bakhawadas to pronounce and then wrote corrected forms in red ink directly into the pages of Gatschet’s original notebooks. He also prepared typescripts of Gatschet’s Tualatin texts.

Bakhawadas’s next contribution to academic scholarship came in the winter of 1928–1929, which he spent in Berkeley, California, at the home of two freelance linguists, Jaime de Angulo and his wife Lucy S. (Nancy) Freeland. Franz Boas, the founder of modern American anthropology, had commissioned these linguists to salvage what they could of Tualatin, by then believed to be spoken only by Bakhawadas. Among the fruits of this collaboration was an extended narrative in Tualatin devoted to the speaker’s Grand Ronde childhood.

Back at the Yakama Reservation in the summer of 1936, Bakhawadas continued this narrative at some considerable length, dictating to the pen of professor Melville Jacobs of the University of Washington. Jacobs was unable to finish all of the work he had planned to undertake with Bakhawadas, owing to the latter’s death from influenza the following winter. He had only half finished reviewing Frachtenberg’s typescripts of Gatschet’s Tualatin texts, but he nevertheless published all of them in the third part of his Kalapuya Texts. He made no attempt to publish the childhood narrative, a significant portion of which had not yet been translated into English. Publication of that narrative came only in 2017, thanks to the support of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

In spite of having devoted much of his youth to becoming literate and educated in English, Bakhawadas’s knowledge of traditional culture was by no means inconsiderable. In addition to clarifying aspects of Gatschet’s earlier record, he also contributed significant ethnographic detail to a list of Kalapuyan (Santiam and Tualatin) culture elements that Jacobs compiled for Alfred A. Kroeber, head of the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. That list was to be part of a series of such surveys, but it never appeared in print. Internal evidence in the field version of the list, archived at the University of California, points to Bakhawadas as the sole source of the Tualatin elements and to John B. Hudson of Grand Ronde as the sole source of the Santiam elements. The list shows that both Bakhawadas and Hudson retained considerable knowledge of the ceremonial and religious sides of their Indigenous cultures, while having little to offer regarding material aspects.

This asymmetry is no surprise, considering the rapidity with which Grand Ronde people adopted EuroAmerican material and work culture. But as Commissioner Brunot observed in 1871, this was not the whole story. Traditional beliefs and ceremonial practices were also very much a part of the experience of both Bakhawadas and Hudson.

-

![The picture appears unattributed in Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 1916, in a report by Leo J. Frachtenberg on linguistic fieldwork he conducted with Kenoyer and other informants in 1915.]()

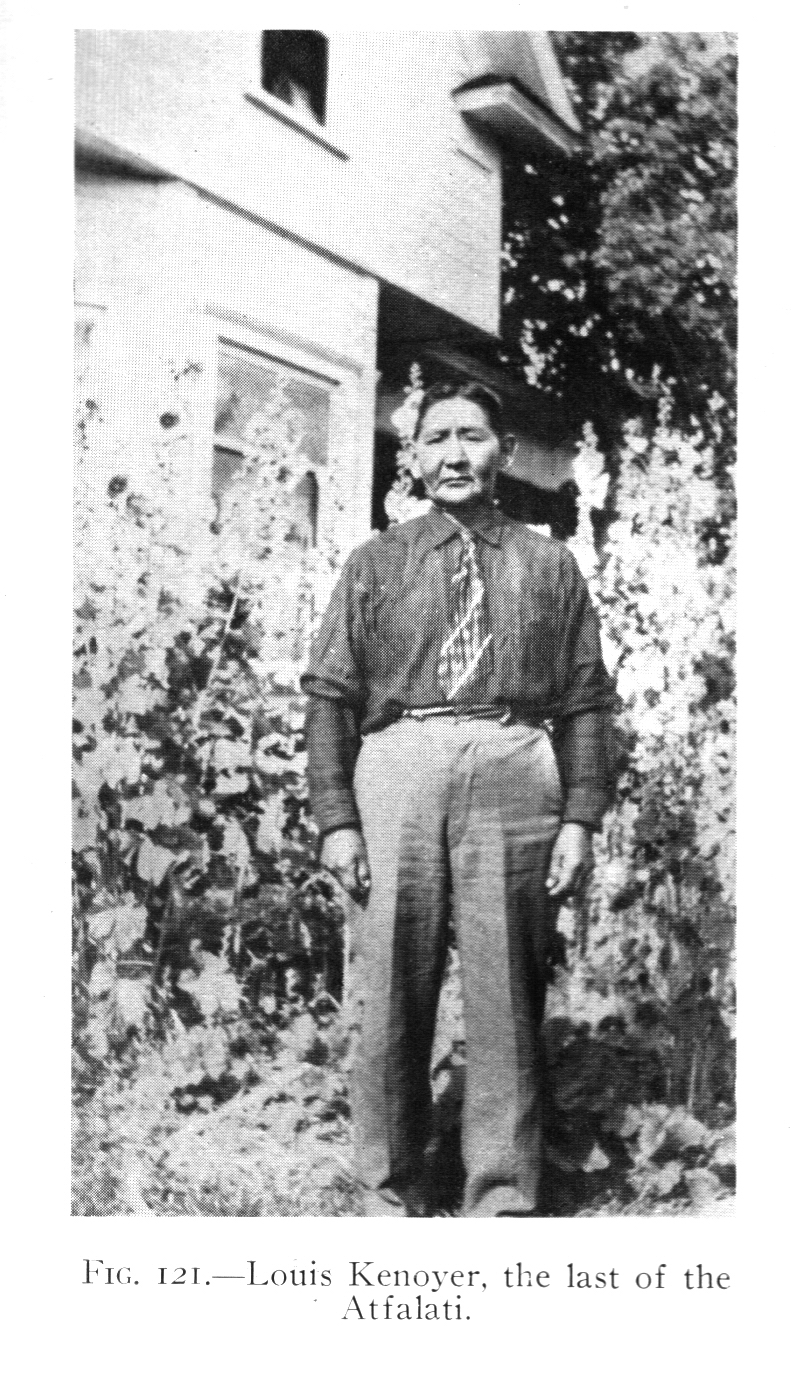

Louis Kenoyer (bax̣awádas), date and location unknown..

The picture appears unattributed in Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 1916, in a report by Leo J. Frachtenberg on linguistic fieldwork he conducted with Kenoyer and other informants in 1915.

-

![]()

Louis Kenoyer in Berkeley, California, in 1928, during his winter-long stay at the home of Jaime de Angulo and L. S. (Nancy) Freeland..

Courtesy Gui Mayo

Related Entries

-

![Chemawa Indian School]()

Chemawa Indian School

Chemawa Indian School, located in the mid-Willamette Valley north of Sa…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)]()

Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)

Melville Jacobs did more to document the languages, cultures, oral trad…

-

![Tualatin peoples]()

Tualatin peoples

Tualatin (properly pronounced 'twälə.tun in English) was the name of a …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Brunot, Felix R. "Report of a Visit to the Reservations in Oregon and Washington Territories by Commissioner Felix R. Brunot." in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Year 1871, 116-153. Washington, D.C: Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1871.

Jacobs, Melville. "Kalapuya Texts." University of Washington Publications in Anthropology 11 (1945).

Kenoyer, Louis, Henry Zenk, and Jedd Schrock."My Life, by Louis Kenoyer": Reminiscences of a Grand Ronde Reservation Childhood. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. 2017