Bonnie Hill was an important figure in the herbicide-spraying controversies in Oregon forests during the 1970s, her efforts contributing to a permanent ban on using 2,4,5-T and Silvex in the United States. An English and journalism teacher at Alsea High School, she also served the Oregon Department of Education in establishing writing standards for Oregon schools and frequently contributed to the Oregon English Journal. One of her students, Libra Hilde, now a professor at San Jose University, remembers Hill as the teacher who provided a model for “women’s intellectual capability and strength.”

Bonnie Leiter was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1945, to Katherine and Eugene Leiter. Katherine earned a music degree from Smith College and Eugene received a medical degree from Case Western University. After serving in the U.S. Army during World War II, he joined the Air Force and was attached to the Surgeon General’s office in Washington, D.C. Bonnie Leiter attended Ursuline Academy in Bethesda, Maryland.

After graduating, Leiter enrolled in Marquette University’s nursing school, where she met Tony Hill. They married and had a child before moving to Eugene, where Tony worked for U.S. Plywood and Bonnie attended the University of Oregon. She received a bachelor’s degree in 1971. With a second child, the family moved to Alsea, where Hill taught English at Alsea High School and earned a master’s degree from UO. The couple had two more children in the late 1970s.

Bonnie Hill’s long record of community service began in the Amazon family housing complex in Eugene, where she led efforts to establish a pre-school and kindergarten. After settling in Alsea, she wrote a grant that helped fund the Alsea Clinic. After she had a miscarriage in the spring of 1975—and her physician found no plausible explanation—her activism changed focus.

Attending classes at the UO two years later, she read about the effects of TCDD, a dioxin present in the herbicides 2,4,5-T and Silvex, in which studies indicated a correlation between TCDD and spontaneous abortions. She learned that timber companies sprayed herbicides on clear-cuts during the spring to kill hardwoods competing with Douglas-fir seedlings, and she began gathering maps of areas sprayed, the timing of spraying, and their proximity to homes. She got in touch with local women who reported miscarriages in the spring, and by early 1978 had identified eleven miscarriages involving eight women. She and the women drafted and mailed letters to thirty-five state and federal agencies, urging them to look into the association between spraying with 2,4,5-T and Silvex and spontaneous abortions.

The letters prompted the Environmental Protection Agency to interview the women and fill out questionnaires. Because the EPA already had evidence indicating the toxicity of TCDD, it issued a temporary ban in March 1979 for spraying herbicides on forestland. The EPA’s subsequent study of a 1,600-square-mile area in the Coast Range confirmed significant correlations between miscarriages and spraying. The journal Science identified Bonnie Hill as “the 33-year-old English teacher in Alsea who uncovered the apparent link and wrote to the EPA two years after her own miscarriage.” EPA administrator Douglas Costle praised the Alsea study for its “dramatic and troubling analysis of TCDD (dioxin) exposure concerns.”

The lumber industry attacked Hill and criticized the EPA’s second Alsea study. Hill testified before the House Forest Subcommittee in May 1979, calmly defending her efforts in assembling the initial survey. She thought it unfortunate that ordinary people had to prove they were exposed to dangerous elements in their environments and that their findings were rarely considered adequate.

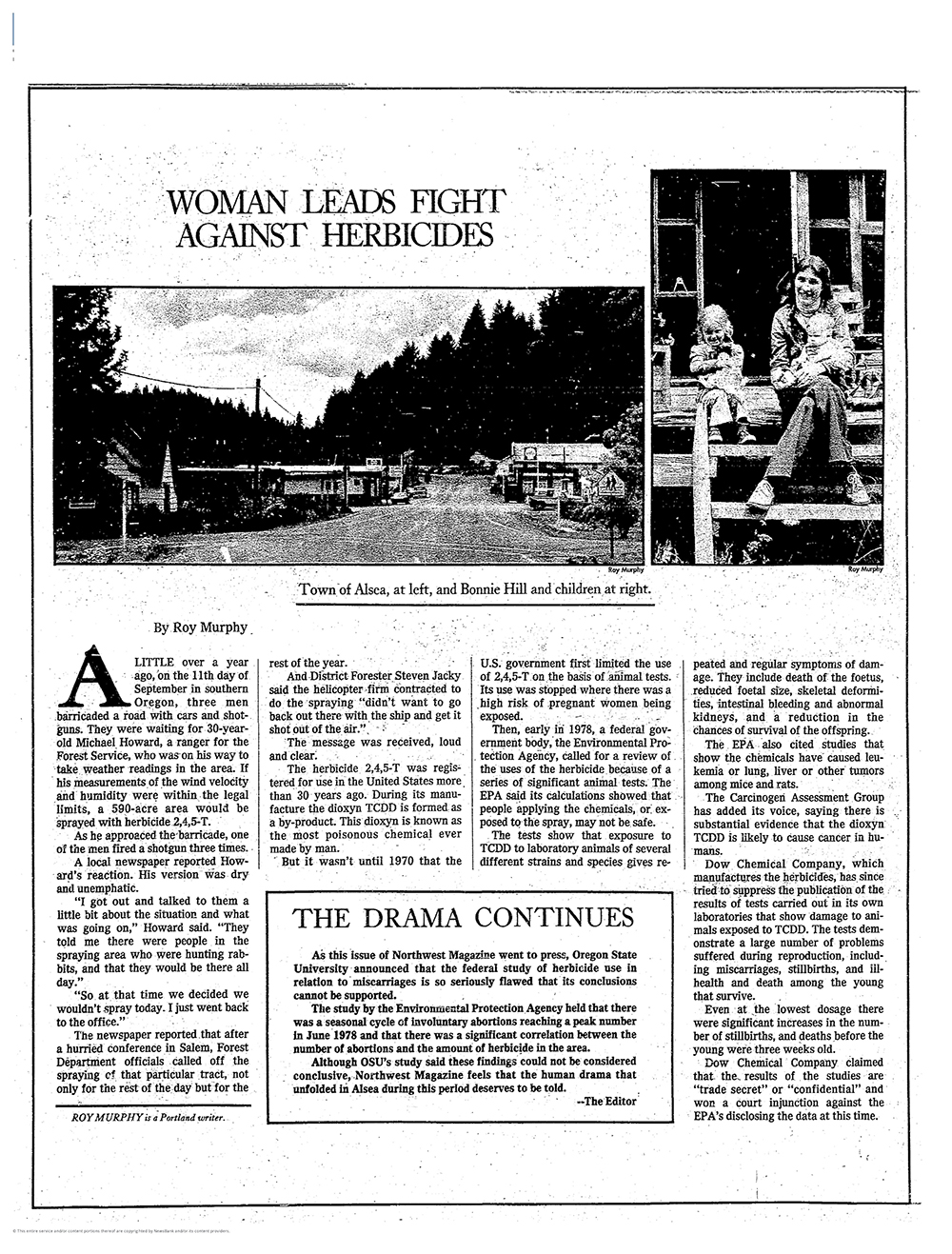

The herbicide controversy in Alsea’s rich timber country brought considerable media attention to Hill and the Alsea Valley. Geraldo Rivera, then a reputable investigative journalist with a weekly television program, interviewed Hill at the family home on the South Fork of the Alsea River. Stories about Hill and the herbicide debate appeared in Family Circle, the New York Times, and Mother Earth News. EPA delisted use of 2,4,5-T and Silvex in 1985.

With the herbicide controversy no longer making headline news, Hill continued teaching English and journalism at Alsea High School, serving on the board of the Alsea Clinic, and providing support for a Benton County branch library in Alsea. She received the Michael Milken Award for outstanding teaching in 1997 and assisted the Oregon Department of Education with its writing standards for public schools.

Hill continued her work on statewide standards after she retired in 2002 and also began publishing Alsea Voice, a monthly community newspaper about the upper Alsea Valley. She died in January 2019.

-

![]()

Bonnie Hill, featured in the Sunday Oregonian, Dec. 2, 1979.

Courtesy Portland Oregonian, December 2, 1979

Related Entries

-

![Alsea (Alcea)]()

Alsea (Alcea)

Alsea is an unincorporated community of about two hundred residents in …

-

![Department of Environmental Quality]()

Department of Environmental Quality

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) administers and en…

-

![Timber Industry]()

Timber Industry

Since the 1880s, long before the mythical Paul Bunyan roamed the Northw…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Arnold, Ron. “Environmentalism, Pesticide Use, and Rights-of-Way.” Transportation and Research Record 859 (1981).

“Chemicals Can Kill.” Northwest Magazine (1979)

"Testimony on the Possible Link Between Herbicides and Miscarriages in the Coast Range of Oregon." Forest Subcommittee, Agriculture Committee, U. S. House of Representatives, Hearing Record, 1979.

Kramer, Larry. “8 Oregon Women Seek Link of Herbicides to Miscarriages.” Washington Post, August 15, 1978.

Layne, Linda L. “In Search of Community: Tales of Pregnancy Loss in Three Toxically Assaulted U.S. Communities.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 29.1 (Spring-Summer 2001): 25-50.

O’Neill, Larry. “A Letter from Alsea.” EPA Journal 5.4 (1979).

“The Plowboy Interview: Bonnie Hill.” The Mother Earth News 72 (Nov./Dec. 1981): 17-24.

Smith, Jeffrey R. “EPA Halts Most Use of Herbicide 2,4,5-T.” Science 3 (Mar. 16, 1979).