The 1913 wreck of the Glenesslin is one of Oregon’s most enigmatic and often-discussed shipwrecks because of the strangeness of its grounding. It is unique in Oregon history for both its oddity and the mystery clinging to it: occurring on a calm day, with no apparent cause, followed by an investigation that appeared to leave important questions unanswered. A three-masted, square-rigged British ship, the Glenesslin had been sailing the seas since 1885. It had been built in Liverpool for the British firm C.E. De Wolfe and Co. and had an excellent reputation for speed during the years when much of the world’s goods were transported by sail.

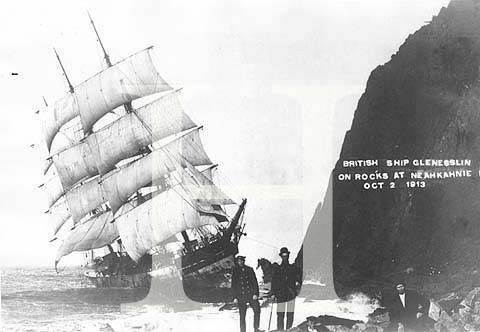

October 1, 1913, was a clear, calm day in Manzanita on the north Oregon Coast. The Glenesslin was 176 days out of the port of Santos, Brazil, bound for Portland and carrying no cargo. In the early afternoon, residents of Manzanita were staggered to see the graceful clipper ship, its sails full of wind, steer directly for the rocks at the base of Neahkahnie Mountain and crash. The impact jarred the ship and tore a gash in the iron hull.

The crew threw a line onto the rocks using a breeches buoy, which was secured by S.G Reed, owner of a local tavern, his clerk Walter Cain, and two other local men. The twenty-one-man crew clambered to safety. Captain Owen Williams said little to the press or onlookers once he reached shore, but witnesses reported that he appeared to be inebriated, as were several other crew.

Captain Versey, the Lloyd’s of London insurance surveyor from Portland who visited the wreck the next day, noted that rocks had pierced the ship’s hull and advised its immediate sale. Alex Bremmer and John Caavinen of Astoria bought the ship for $560. Finding it difficult to bring salvageable items to shore, they sold the ship to Arthur Bell in Nehalem for a price rumored to be a hundred dollars. Sources at the time speculated as to whether the salvage rights were worth even that much.

The subsequent court of inquiry consisted of Thomas Erskine, the British consul at Portland, Captain Davidson of the British ship Lord Templeton, and Captain Dalton of the British steamer British Knight. When they met, less than two weeks after the wreck, they took testimony from officers and crew. A Chinese steward reported that he had tried to warn the mate at the helm, L. Peterson, that the ship was veering too close to shore, but his warning was unheeded. Williams testified that he took a nap after lunch and when he was called to the deck he was not told the ship was in a dangerous position. Officers gave conflicting testimony about when Williams had been drinking and whether his head was clear when the Glenesslin struck the rocks.

Captain Williams’s license was suspended for three months on a charge of negligence, and Second Mate John Colefield’s license was suspended for six months, also for negligence in running so close to shore, even while under orders, without calling for the captain. First Mate F.W. Hawarth was reprimanded for failing to act immediately on being notified of the danger. The crew scattered, some shipping out on other vessels, some remaining in the area to become lumbermen, and others returning home. Williams returned to England.

Despite the verdict, uncertainty haunts the wreck of the Glenesslin. There was much theorizing in maritime circles and by historians and coastal residents that the wreck may have been staged to collect the insurance payment, which would have brought in more money to the De Wolfe Company than selling the ship. The insurance company ultimately reimbursed the $30,000 value of the ship ($780,000 in 2019 dollars), and the loss was recorded as a result of inexperienced first and second officers.

The Glenesslin, whose first and second mates on its final voyage were young and unseasoned, exemplifies the tragedies with which the Age of Sail ended. The transition to steam was a difficult time for square-rigger captains, who were often unable to get competent crew as the best seamen took positions on steamships.

A suite of extraordinary photographs helped seal the Glenesslin’s story in Oregon coastal traditions. Area resident Paul Bartels had the remarkable luck to be present at the event with “one of those old-timey cameras, you know the kind you have to throw the black rag over your head,” as he later recounted to the Cannon Beach History Center. He recorded iconic images of the ship, sails full, tilted on the rocks of Neahkahnie. The photographs are in the collections of the Cannon Beach History Center and Museum.

-

![]()

Wreck of the Glenesslin, 1913.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Orhi45054

-

![]()

Glenesslin against the rocks at the base of Neahkahnie Mountain, 1913.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., 003917

Related Entries

-

![Neahkahnie Mountain]()

Neahkahnie Mountain

Neahkahnie Mountain, about twenty miles south of Seaside, is a prominen…

-

![Shipwrecks in Oregon]()

Shipwrecks in Oregon

Approximately three thousand ships have met their fate in Oregon waters…

-

![Tillamook Rock Lighthouse]()

Tillamook Rock Lighthouse

Tillamook Rock Lighthouse sits on a rock a mile offshore of Tillamook H…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Berry, Kamie. “The Wreck of the Glenesslin: Insurance Fraud or Intoxication?” July 1, 2017. http://blitzlift.com/the-wreck-of-the-glenesslin-insurance-fraud-or-intoxication/

Cannon Beach History Center and Museum. “Reflections on the Past: History of the Stormy Seas.” Posted November 19, 2016. https://cbhistory.org/blog/general/reflections-on-the-past-history-of-the-stormy-seas/

Gibbs, James A. Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast. Portland, Ore.: Binfords and Mort, 1957.

Kozik, Jennifer and Maritime Archaeological Society. Shipwrecks of the Pacific Northwest: Tragedies and Legacies of a Perilous Coast. Lanham, MD: Globe Pequot, 2020.

“Glenesslin Case Heard by Court. Captain’s Condition When Ship Struck Rocks at Necarney Subject of Inquiry.” Morning Oregonian, October 10, 1913, p. 20.

“Chinese Salts Sign Again. Glenesslin’s Crew Scattering and Master to Leave Soon.” Morning Oregonian., October 18, 1913, page 18.

Williams, William Appleman. “Notes on the Death of a Ship and the End of a World: The Grounding of the British Bark Glenesslin at Mount Neahkahnie on 1 October 1913.” The American Neptune XLI.2 (April 1981).