Situated near the confluence of the Williamson and Sprague Rivers, the area near the Chiloquin townsite served as a seasonal camp for Indigenous peoples for a period well beyond living memory. Although not "established" until 1910 or so, once the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived there, Chiloquin quickly became the largest town on the Klamath Indian Reservation and the third largest in Klamath County, behind Klamath Falls and Merrill. Although the reservation was terminated beginning in 1954, its legacy endures in Chiloquin, which remains in the upper quartile in ethnic diversity among incorporated communities in Oregon.

The Klamath possessed a common language, with only a few linguistic differences, over a wide territory in south-central Oregon. They have often been divided into six bands, each with a specific locality, and the ancestral camp at Chiloquin fell into the small Agency Lake band, whose numbers paled in comparison to their southern neighbors on the lower Williamson. The name Chiloquin is derived from Chay-lo-quin, Chaloquenas, or Chaloquin, the name of a Klamath warrior who was still alive when the treaty with the United States was signed in 1864. Chiloquin as a surname continues into the present, as the family occupied land in and near the town well into the twentieth century.

The first recorded visit by Europeans to the vicinity of Chiloquin was in 1826, when envoys of the Hudson’s Bay Company traversed the area, scouting for beaver to serve the fur trade. In about 1910, a recognizable town began to take shape in response to the Southern Pacific Railroad (SPRR) having arrived in Klamath Falls a year earlier, with a connection to the main north-south route at Weed, California. Workers continued building track northward, and the name of a station stop was established as Chiloquin in 1911. A depot and post office at Chiloquin were opened the following year, but a federal court case against the Southern Pacific resulted in the rail line ending just north of the town, at Kirk, and the town’s growth was fewer than a hundred residents over the next decade.

The incorporation of Chiloquin in March 1926 stemmed from the convergence of economic factors. The first was the settlement of a court case that allowed the Southern Pacific to resume building what became its main north-south rail line over Willamette Pass to Eugene. At about the same time, logging that utilized railroads for accessing stands of Ponderosa pine and other sawtimber reached its zenith on land east of the Cascade Range. Chiloquin’s location on the SPRR attracted several lumber mills and box factories that created employment in the town, which boasted four hundred residents by the time of its incorporation. A fire in 1926 did enough damage that the newly elected town council determined that only fireproof brick buildings could be erected in the downtown business district.

After the railroad arrived in 1911, Chiloquin was seen as the gateway to the Klamath Indian Reservation. The official contact point for services to tribal members was the Klamath Agency, located about six miles west of Chiloquin, roughly midway between the town and the unincorporated hamlet of Fort Klamath. By 1941, there were reportedly twenty-six trains daily from Chiloquin, most of them carrying forest products, sheep, and cattle. The town also served as the freight distribution point for most of northern Klamath County. Much of the timber came from reservation land, and more than half of Chiloquin’s five hundred residents were tribal members.

While tribal land on the reservation (862,622 acres in 1954) was sufficiently productive to provide enrolled members with supplementary income immediately after World War II, many members of the Klamath Tribes––a confederation formed as part of the 1864 treaty of the Klamath, Modoc, and a northern Paiute band called the Yahooskin Snake––faced daunting economic challenges. Some left the reservation to live in Klamath Falls or elsewhere, while others stayed to pursue agricultural work or to graze cattle or sheep. A portion of the tribal assets were sold to non-Natives, but most of their land base formed the heart of what became the Winema National Forest. Private holdings derived from former tribal holdings have hampered access by members of the Klamath Tribes to traditional hunting and gathering.

The timber industry was one of the few employment options available to landless tribal members, and many accepted lump-sum payments from the federal government as part of their agreement that the Tribes would be “terminated.” The Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin were the largest tribal entity ever terminated in the United States, affecting 1,659 enrolled members during the first phase (1954 to 1961), followed by the dissolution of the 474 “remaining members” by 1973. The Klamath Tribes were “restored,” but without a land base, in 1986, and the center of tribal government was moved to Chiloquin.

Enrolled tribal members constitute fewer than half of Chiloquin’s 770 residents in 2015, but tribal enterprises––including the Kla-mo-ya Casino, opened in 1997––account for a significant part of the local economy. The community retains only traces of the timber industry and is now last in per capita income among Oregon’s incorporated cities.

-

![]()

Chiloquin, 1926.

Courtesy Chiloquin News -

![]()

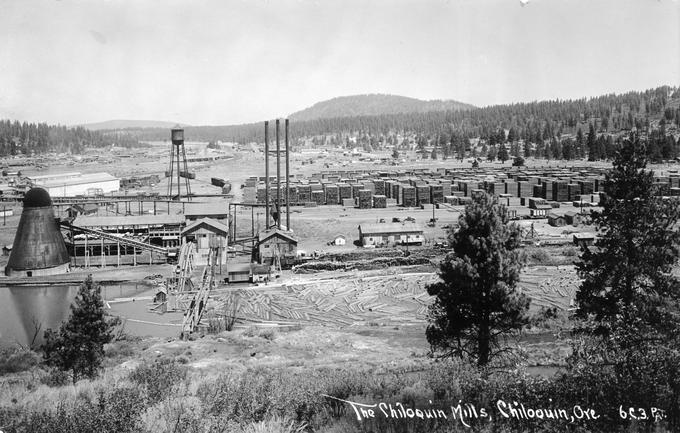

The Chiloquin Mills, c.1932.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

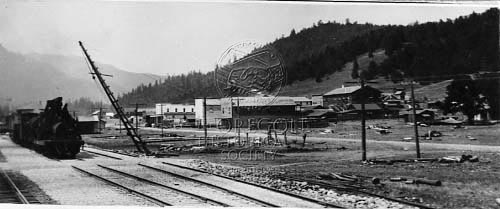

Southern Pacific railroad comes to Chiloquin, along the "Natron Cutoff," 1926.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrHi73626

-

![]()

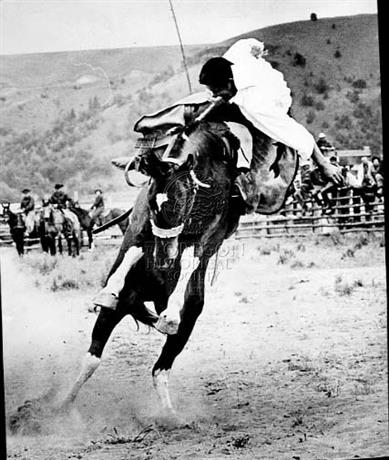

Mel Chiloquin, of Chiloquin, Oregon, competes on a bucking bronco, Tygh Valley All-Indian Rodeo..

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 015216

-

![]()

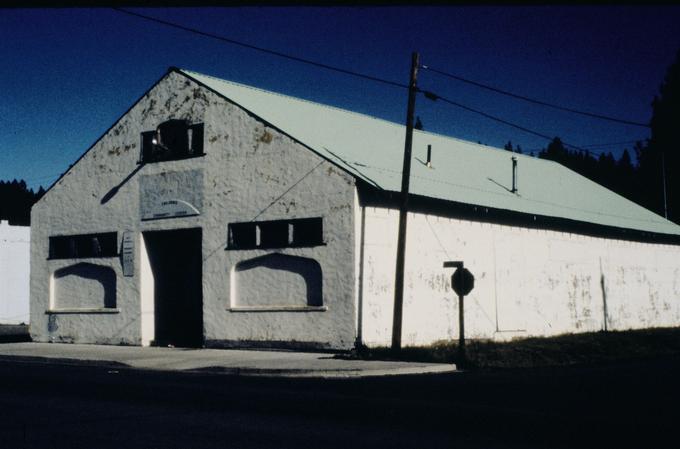

Chiloquin Community Hall, built in 1915 (razed in 1993)..

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries

Related Entries

-

![Edison Chiloquin (1923-2003)]()

Edison Chiloquin (1923-2003)

Edison Chiloquin earned international attention in 1974 when he refused…

-

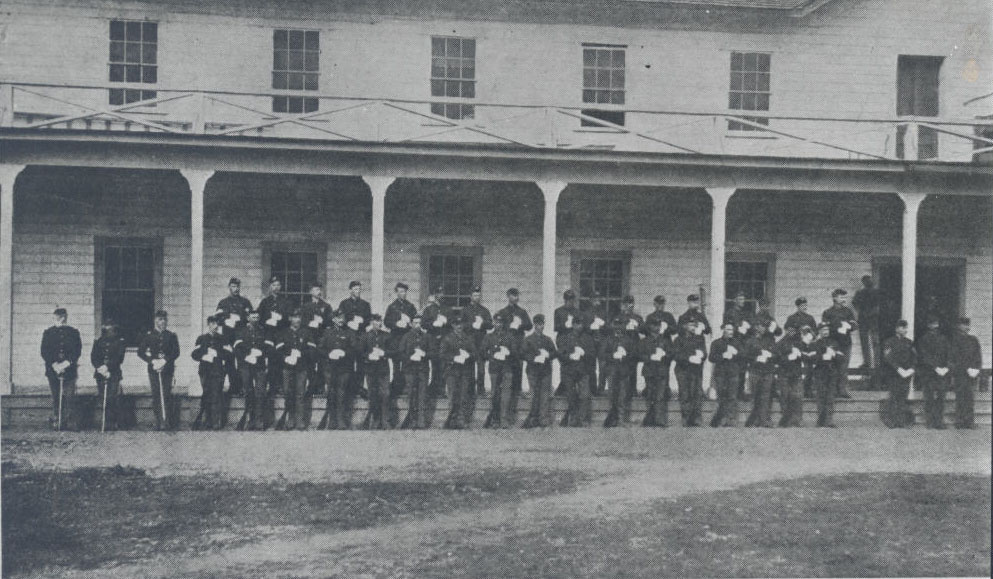

![Fort Klamath]()

Fort Klamath

During the Civil War era, tens of thousands of people immigrated to the…

-

![Termination and Restoration in Oregon]()

Termination and Restoration in Oregon

Termination Of the federal-Indian policies introduced to American Indi…

-

![Timber Industry]()

Timber Industry

Since the 1880s, long before the mythical Paul Bunyan roamed the Northw…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"A History of the Chiloquin Region.” Klamath Watershed Partnership and Friends of the Chiloquin Library. (Accessed January 3, 2020.)

Stern, Theodore. The Klamath Tribe: A People and Their Reservation. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966.

Zucker, Jeff, et al. Oregon Indians: Culture, History and Current Affairs—An Atlas and Introduction. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1983.