Civilian Public Service Camp #56, on the central Oregon Coast four miles south of Waldport, was active from late 1942 to December 1945. It was originally built in 1941 as a Civilian Conservation Corps camp and named Camp Angell to honor Albert G. Angell, a former U.S. Forest Service employee. But the United States’ entry into World War II in December 1941 reduced and eventually ended enrollment in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and the camp opened instead the following year as one of 150 work camps for conscientious objectors, who did work as an alternative to military service during the war.

Civilian Public Service (CPS) was a complex public-private partnership originally proposed by the three “historic peace churches”—the Church of the Brethren, the Society of Friends, and the Mennonite Church—and signed into law as part of the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. The physical sites and work equipment were provided by the federal government, and operational expenses and administration at the camps were divided among the peace churches. Camp #56 was run by the Brethren.

Most of the fifty thousand conscientious objectors in World War II served in some form of military noncombatant role. About twelve thousand were assigned to CPS, most of them in rural areas where they did work similar to that done by the CCC. Depending on a camp’s location, the work could be in forestry, soil conservation, agriculture, dairy, wildlife management, or even weather research. The COs worked eight and a half hours a day, six days a week, for no pay except a monthly allowance of $2.50, with holidays on Sundays and Christmas Day. The rules for length of conscription changed a number of times, but for most of them, it would last the duration of the war (unknown at the time) plus six months. The justification was that soldiers returning from the war should have the first chance at available jobs.

Camp #56, in the heart of Oregon’s logging country, focused on tree planting, road and trail building, and fighting forest fires. During the first year of the camp's existence, the men planted more than two million trees in the Blodgett Tract, an area between Waldport and Yachats that had been logged for spruce to make airplanes during World War I. They crushed nearly ten thousand tons of rock and laid nine miles of gravel roads; built more than three miles of fire trails; maintained almost forty acres of Forest Service parkland; helped fight seven forest fires in Oregon and Washington; and built a fire lookout tower on Blodgett Peak. Most of the work allowed the men to return to camp each night, although sometimes circumstances required a temporary “side camp,” where they would stay for an extended period until the particular project was completed.

Many of the “campers,” as they were sometimes called, were religious conservatives, content to do their work, study Bible lessons, and wait until the war ended so they could return to their farms and quiet lives. But some were political or philosophical objectors who wanted to do more than dig ditches or plant trees. In response to that desire, some camps organized what they called after-hours “schools,” where the COs could explore ways to apply their pacifist ideals in other aspects of life. A camp in Virginia, for example, had a group that studied nutrition and health; another in Pennsylvania focused on race relations; a sister camp in Oregon, CPS #21 in the Columbia Gorge, examined a general approach to pacifist living.

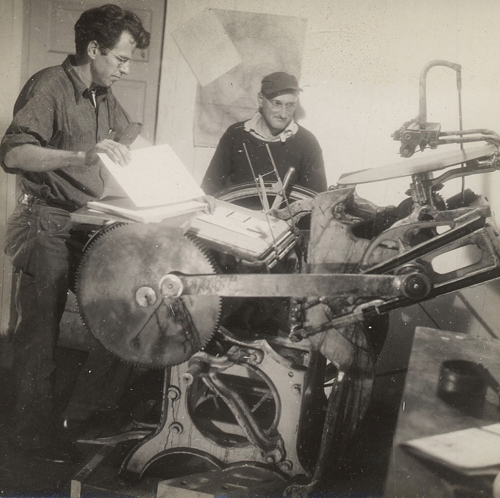

Out of the roughly one hundred COs in the Waldport camp, a small group of creative-minded men put in their fifty-plus hours of manual labor and then spent their nights writing and drawing and later printing their work on a mimeograph machine in the camp office. They published a weekly newsletter called the Untide, named as a satire of the official camp newsletter, the Tide, which they felt was too stodgy. The motto of the newsletter was “What is not Tide is Untide,” and they filled it with news, opinion, art, and humor.

What began as a lighthearted protest grew into a serious creative venture and became an officially sanctioned program called the Fine Arts Group at Waldport. In the same way that the "schools" at other camps focused on particular subject areas, Fine Arts became a center for artists, writers, musicians, and actors in the CPS system, who could request a transfer to the Waldport camp. The group numbered between ten and twenty men at a given time, depending on how many COs were allowed to transfer. They found an old printing press in a Waldport secondhand shop and published poetry booklets under the imprint of the Untide Press. They also produced plays, art, and music—all during their nonwork hours, with little money or resources.

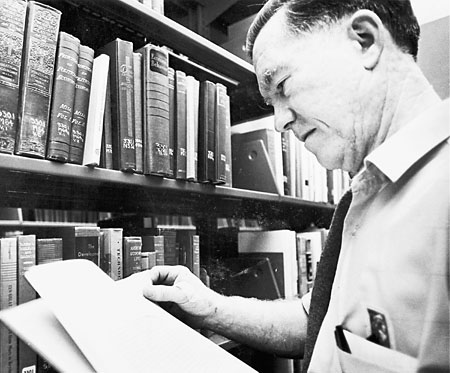

This talented group included poet William Everson, who in the 1950s became Brother Antoninus, the “Beat Friar”; Broadus “Bus” Erle, violinist and a founder of the New Music Quartet in 1948; Adrian Wilson, book designer, fine arts printer, and recipient of a MacArthur “genius grant” in 1983; Kermit Sheets, founder of the Centaur Press in 1949 and San Francisco’s Interplayers Theatre in 1962; Kemper Nomland Jr., who became a modernist architect in Los Angeles; and internationally renowned sculptor Clayton James. Others published by or interacting with the Fine Arts Group included artist Morris Graves and poet William Stafford (both CO’s who served elsewhere), as well as fiery antiwar poet Kenneth Patchen and iconoclastic author Henry Miller.

After the war, some Fine Arts members went to San Francisco, where they got involved in spoken-word performance, theater, music, and other creative work. They helped plow the ground for what became known as the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance of the mid-1950s, which attracted Beat Generation writers Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg.

The building that housed the workroom for the Fine Arts Group was moved in 1988 to Waldport, where it is now the Waldport Heritage Museum.

-

![]()

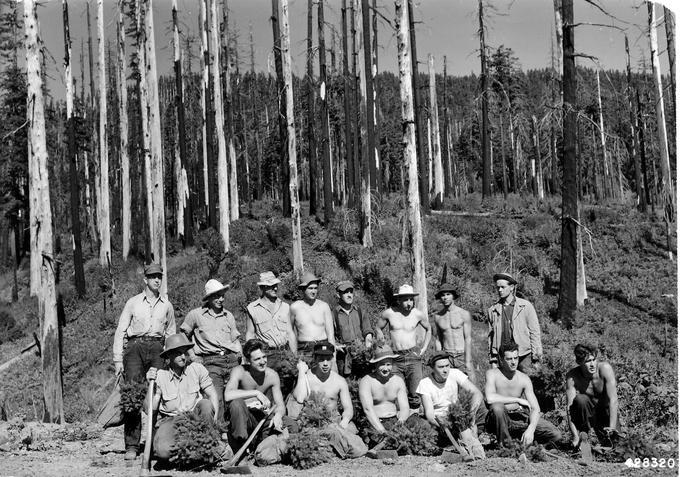

Tree planting crew of Conscientious Objectors from Waldport CPS Camp, planting near Mary's Peak.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

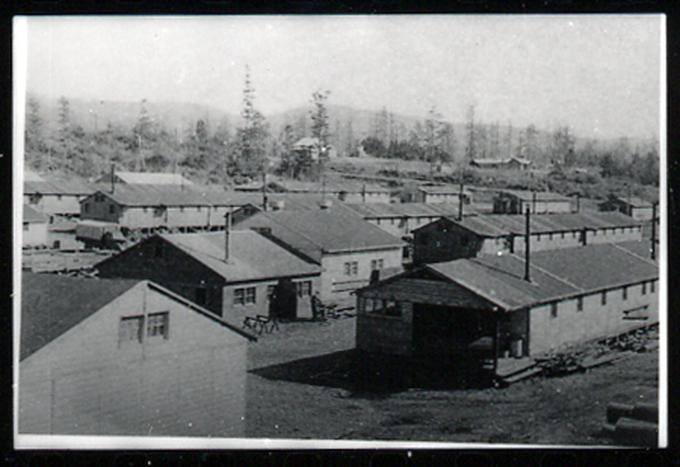

A Civilian Public Service camp in Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries, Siuslaw Forest Coll. -

![]()

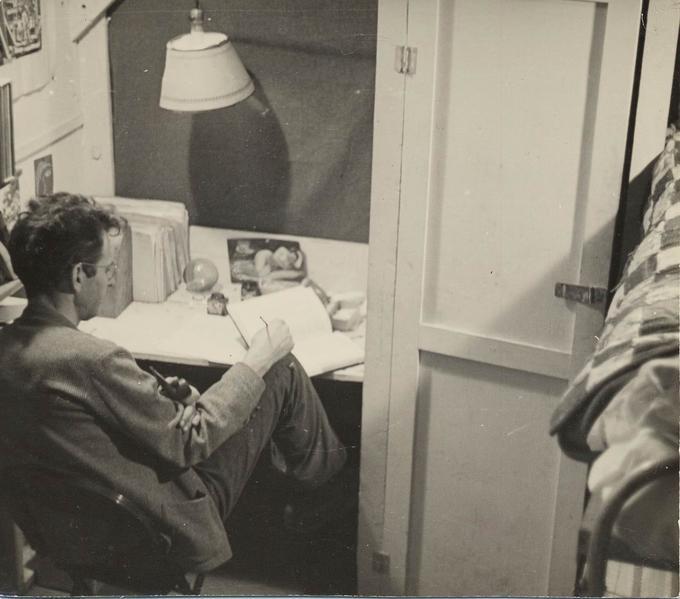

Musical performance at Civilian Public Service Camp #56, c.1944.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

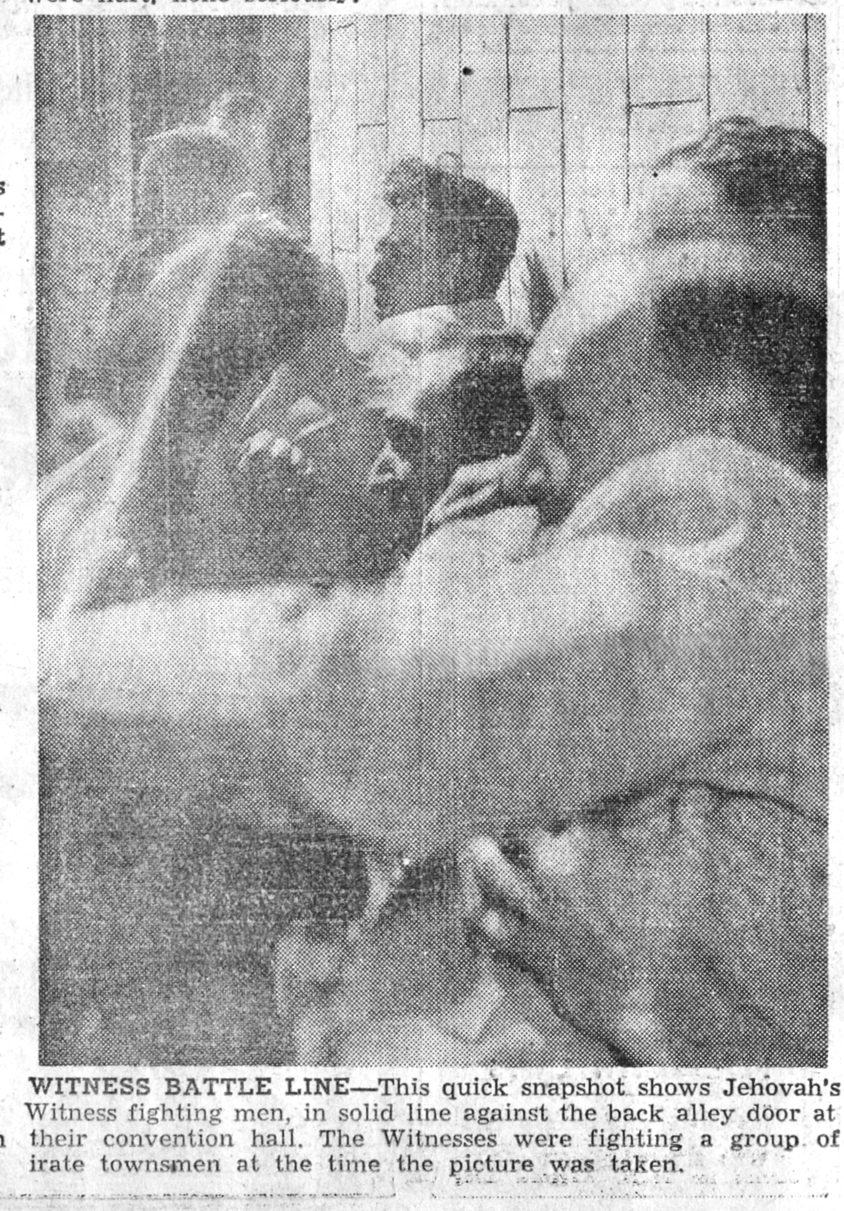

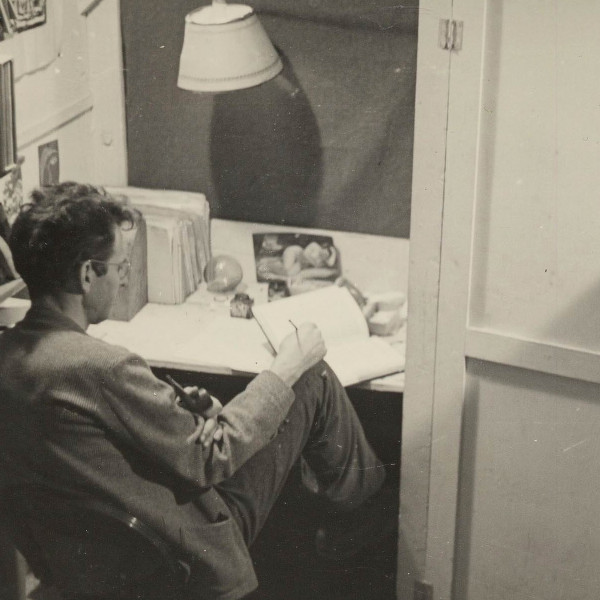

William Everson, Civilian Public Service Camp #56, c.1942.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries

Related Entries

-

![Civilian Conservation Corps in Coos County]()

Civilian Conservation Corps in Coos County

From 1933 to 1942, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) enrollees in Coos …

-

![Civilian Public Service Camp #21]()

Civilian Public Service Camp #21

Civilian Public Service Camp #21 opened in November 1941 at Wyeth, a fe…

-

![Jehovah's Witnesses Riots, 1942]()

Jehovah's Witnesses Riots, 1942

On Sunday, September 20, 1942, nearly a thousand residents of Klamath F…

-

![Untide Press]()

Untide Press

The Untide Press (1943-1951) was a small poetry press founded at Camp A…

-

![William Everson (1910-1994)]()

William Everson (1910-1994)

William Oliver Everson, a prominent poet in the San Francisco Renaissan…

-

![William Stafford (1914-1993)]()

William Stafford (1914-1993)

William Stafford, one of America’s most widely read poets, was born in …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

McQuiddy, Steve. Here on the Edge. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2013.

Kovac, Jeffrey. Refusing War, Affirming Peace: A History of Civilian Public Service Camp No. 21 at Cascade Locks. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2009.

Sibley, Mulford Q. and Philip E. Jacob. Conscription of Conscience: The American State and the Conscientious Objector, 1940-1947. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1952.

Stafford, William. Down In My Heart. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2006.