Letitia Carson, a nineteenth-century farmer and homesteader, was one of the first Black women to settle in Oregon. In the 1850s, she brought two successful lawsuits against a white defendant over her right to own property. She later became the first Black person, and one of the first women, to file a land claim in Oregon under the Homestead Act of 1862.

Letitia was born into slavery in Kentucky between 1814 and 1818. By September 1844 she was living in Missouri with David Carson, a White man who was the father of her unborn child. David was born in 1800 in County Antrim, in what is now Northern Ireland. He immigrated to the United States in the 1820s or 1830s to join his siblings in North Carolina. By 1839 he was living in Platte County, Missouri, and the next year he swore allegiance to the United States in pursuit of citizenship, which he received in October 1844.

In the spring of 1843, American settlers in the Willamette Valley created a provisional government and established the conditions for land claims in the Oregon Country. In May 1845, David Carson joined more than a thousand emigrants in a journey from Missouri to Oregon. He traveled with one wagon, one cow, eight oxen, two horses, four guns, 600 pounds of bacon, 600 pounds of flour, three White men, and one woman—Letitia. The timing of Letitia's emancipation is unknown. While Letitia was likely Carson's slave at some point, she would later claim to have been his free domestic servant and identified as his widow after his death. On June 9, 1845, in present-day Nebraska, Letitia gave birth to their daughter, Martha.

When David and Letitia began their journey, Black people were not allowed to settle in the Oregon Country. The Provisional Government had passed Oregon's first Black Exclusion Law in June 1844, outlawing slavery but allowing slaveowners a three-year grace period before they had to emancipate their slaves or remove them from Oregon. Formerly enslaved Black people would be forced to leave the Oregon Country, and free Black emigrants were barred from settling there. The voters rescinded the law on July 3, 1845, just a few months before David, Letitia, and their child arrived.

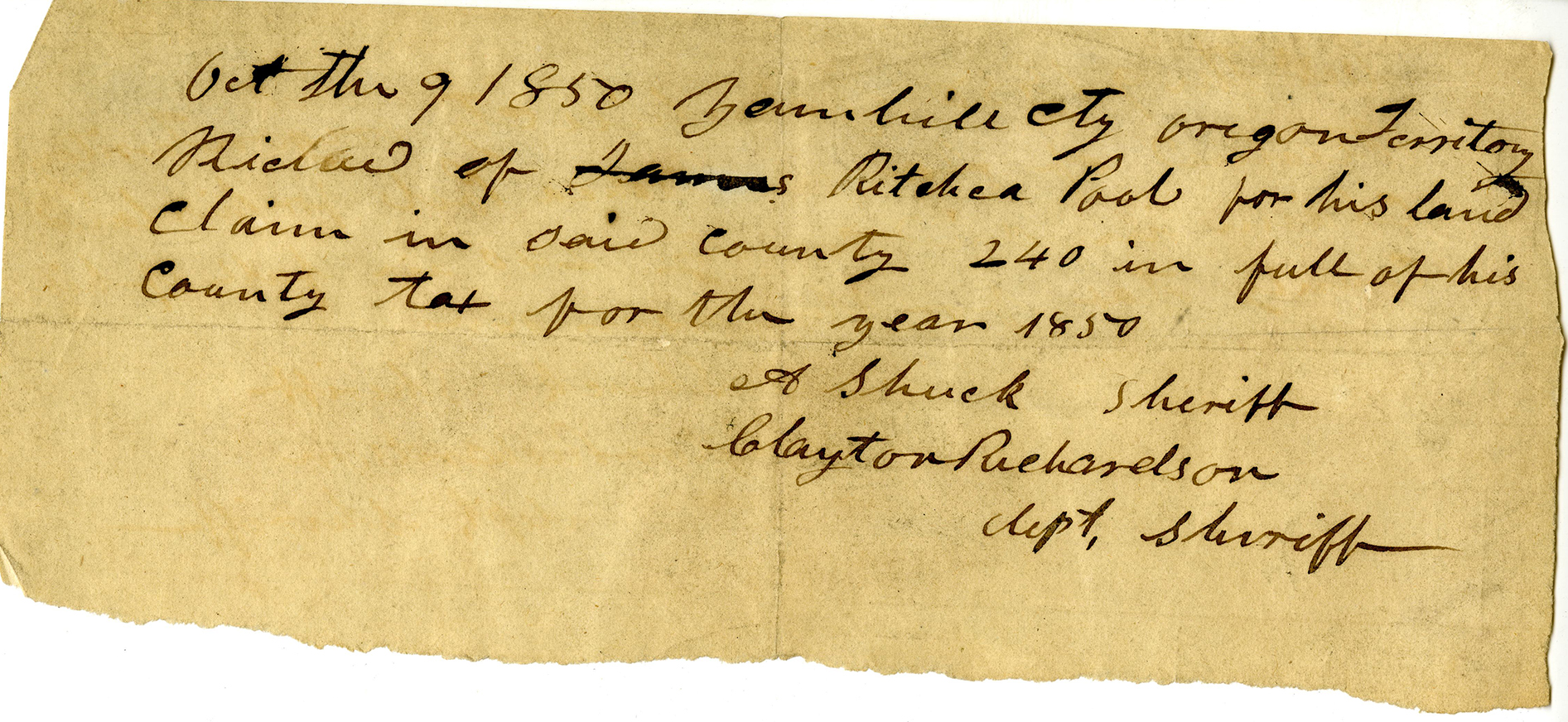

The family reached Oregon City by October 11, 1845. In December, David Carson made a claim for 640 acres in the Soap Creek Valley (now part of Benton County), where they built a home the following spring. David's claim was recorded in Oregon City on October 19, 1847. Over the next several years, David and Letitia grew potatoes and fruit trees and raised hogs and cattle. Letitia gave birth to a son, Adam, on September 15, 1849.

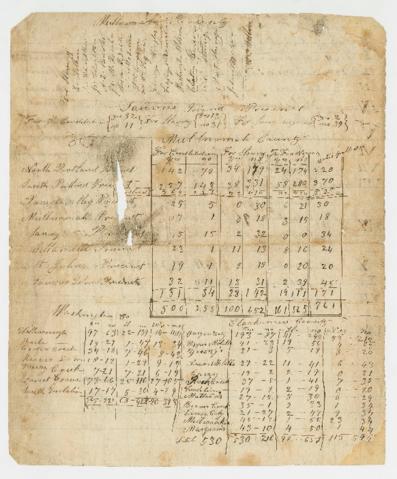

In 1850, the U.S. Congress passed the Donation Land Claim Act, which legitimized the land-claim process established by the Oregon Provisional Government but changed the terms of eligibility. Under the new law, single adult white citizens and mixed-race Indigenous male citizens could claim 160 acres of land, and married men could claim an additional 160 acres through their wives. Up to 640 acres (320 per spouse) claimed under the provisional government—as the Carsons’ claim was—were grandfathered in. Prior claims had to be recertified for inclusion under the terms of the 1850 act. The Carsons’ union was never recognized as a marriage, although there were no laws preventing such a union in Oregon Territory. Still, Black Americans were excluded from claims under the Donation Land Claim Act, which meant that David Carson would not have been able to claim 320 acres through Letitia even if they were married. In 1850, therefore, the Carsons’ 640-acre Soap Creek homestead was reduced by half.

David Carson became ill and died on September 22, 1852. In late November, the Benton County probate court appointed a neighbor, Greenberry Smith, as administrator of Carson’s estate. Smith was tasked with making an inventory of Carson's property, which would be sold to settle his debts and to distribute to his beneficiaries. He had left no will, so it was up to Smith to determine the rightful inheritors. He named David's living relatives in North Carolina, Missouri, and Virginia as beneficiaries, but he did not name Letitia or their children.

Smith held a public auction of David Carson’s land and property on January 4, 1853, and the Carson family’s possessions were sold to the highest bidder. Letitia paid $104.87 to buy back what she could of her own possessions: a washtub, a pot, a skillet and lid, six plates, a bed and bedding, two cows, and a calf.

Letitia Carson and her two children were now homeless. They may have found housing with the Nidey family of Santiam City, who they joined that spring on a 160-mile journey to their land claim in Cow Creek Valley, in Douglas County. In November 1853, Melvina Baker, the Nideys’ eighteen-year-old niece who lived with them, married Hardy Elliff, a settler in Galesville in the upper Cow Creek Valley. Letitia and her son Adam (now known as Jack) went to live with them (Elliff family sources do not mention eight-year-old Martha). Letitia worked as the Elliffs’ domestic servant and acted as a community midwife.

It was during this time that Letitia began to seek damages for her losses in Benton County. On February 27, 1854, Corvallis attorney Andrew Thayer wrote a letter to Greenberry Smith on Letitia's behalf, notifying Smith that he would be filing a lawsuit with the Benton County probate court. The letter reported that in May or June 1845, while on their way to Oregon, Letitia and David Carson had entered into a verbal contract promising that David would make Letitia his sole heir or bequeath his entire property to her in exchange for her living and working with him for the duration of his life. Letitia was suing the estate of David Carson (still overseen by Smith) for the nonperformance of that contract and was seeking damages of $11,200. Notably, this letter (written by Thayer from Letitia's first-person point of view) is the first known instance of her self-identifying as Letitia Carson.

Attorney John Kelsay, who represented Smith, responded at length, alleging that Letitia had no legal standing to sue him. Judge George H. Williams called the case for trial in October 1854. At that point, the defendant's strategy shifted, and Kelsay now argued that Letitia was not entitled to any wages because she had performed the work she had done on the Soap Creek Valley homestead while she was still David Carson's slave. The case now hinged on Letitia's legal status.

Both parties had subpoenas issued to the Carsons’ Soap Creek Valley neighbors and fellow 1845 overlanders. Each was called to testify that Letitia was, or was not, David's slave (a record of their testimonies was not saved). After the jurors deliberated, nine jurors sided with Letitia and three with Smith. Because they could not come to a verdict, Judge Williams ordered that the case be recalled with a new slate of jurors. The case resumed the following spring. On May 7, 1855, twelve white male jurors agreed unanimously in Letitia Carson’s favor. She was awarded $300, representing her back wages and $230 in court fees. Letitia's claim for the illegal sale of her cattle was not considered in the judgment.

Three months later, Thayer filed a second lawsuit against Smith. The case hinged on whether Letitia or David was the true owner of their cattle. William Walker, a Soap Creek Valley neighbor, was deposed in October 1856. According to his testimony, he had gone to help David in August 1852, a month before he died. While milking the cows, Walker had noted that David had a large herd of cattle, to which David replied that only seven of their thirty-four cattle belonged to him while the rest were Letitia's. After deliberating, the jury ruled in Letitia's favor on October 20, 1856, and she was awarded $1,200.

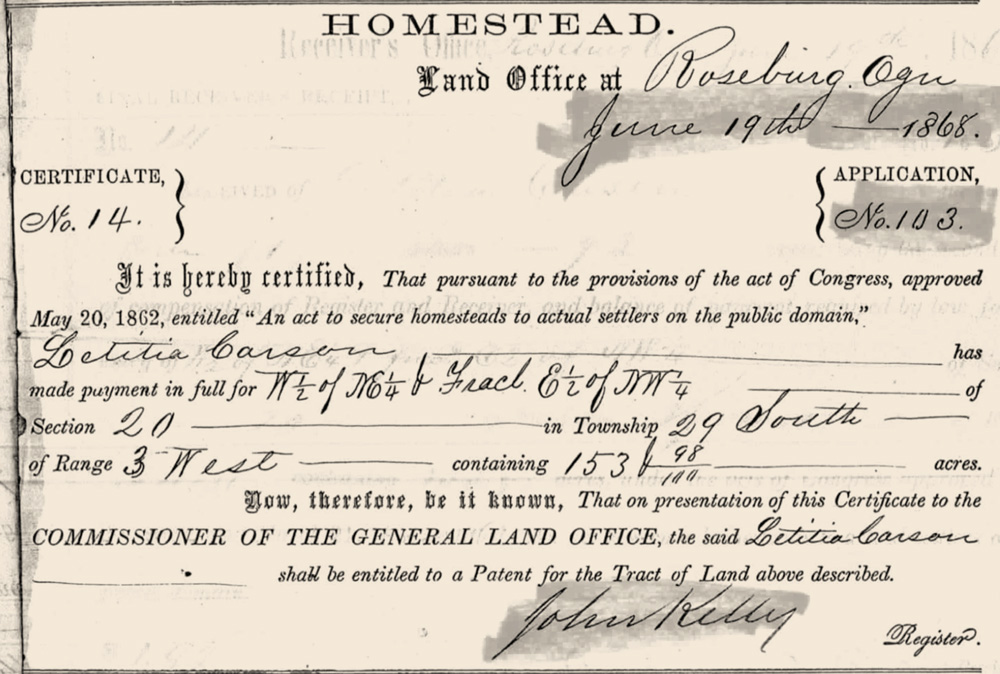

There is no record of Letitia Carson and her children’s whereabouts between the trial and June 17, 1863, when she filed a Homestead Act claim for 154 acres in Douglas County, northeast of the town of Myrtle Creek. The act, which President Abraham Lincoln had signed into law on May 20, 1862, entitled any adult United States citizens to claim up to 160 acres of government land in the West. "Letitia Carson" is written on the signature line of her claim, along with an X and an annotation that reads "her mark," confirming that Letitia filed the claim in person. In the required affidavit, she attested that she was "the head of a family, being a widow having the children" and that she was "a native citizen of the United States."

The use of "widow" may suggest that Letitia considered her relationship with David to be that of a married couple, but it could also have been an effort to falsely suggest that she had been married and to ensure that her children could inherit her land claim. Letitia's assertion of citizenship is also significant. The 1857 Dred Scott v. Sanford decision by the U.S. Supreme Court had declared that Black Americans could not become United States citizens. The recorder at the land office would have seen that Letitia was a Black woman and therefore ineligible for citizenship. He signed the affidavit nonetheless, suggesting ignorance of, or indifference to, the U.S. Supreme Court's decision.

Letitia Carson settled her claim and began making the required improvements to her land. On June 19, 1868, after the required five-year residency period, she filed for a homestead certification. Her neighbors testified that she had improved the land by constructing a one-and-a-half-story log house, a barn, a granary, and a smokehouse and that she had planted about a hundred fruit trees. The 1869 Douglas County Tax Roll shows that she had thirty-nine head of cattle, four pigs, and a horse. The first federal patents certifying title to Homestead Act claims in Oregon were signed on October 1, 1869. Seventy-one Oregonians, including Letitia Carson, completed the process and were issued a homestead patent that first year. Letitia was the first Black person, and one of only four women, to be granted a homestead in her own name that year.

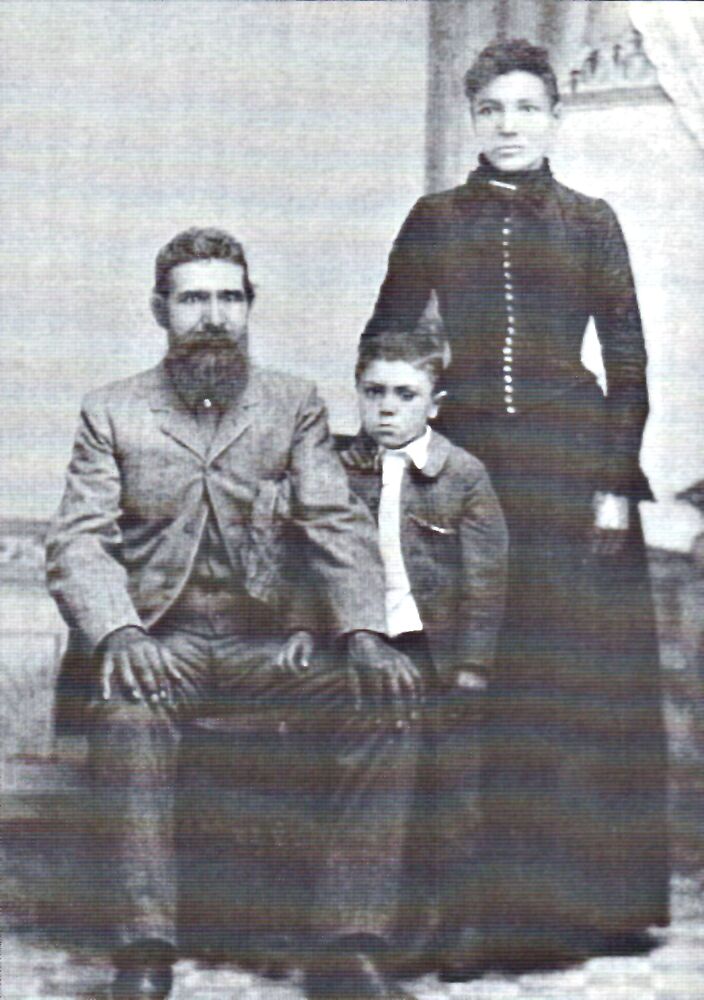

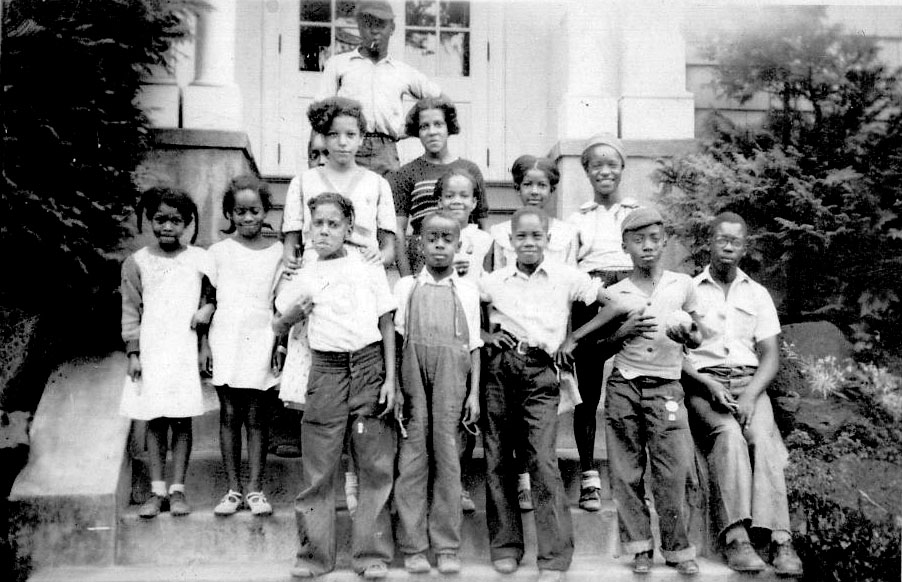

The 1870 census for the Myrtle Creek District lists Letitia Carson as the head of household and living with her nineteen-year-old son Jack, now known as Andrew. Her daughter Martha lived in nearby Canyonville with her French-Walla Walla husband Narcisse Lavadour, their seven children, and a daughter from a previous relationship. In 1885, Martha and Narcisse moved with their children to the Umatilla Indian Reservation. They would have three more children together before Narcisse's death in 1893. Martha Carson died in 1911 and was buried in the Athena Cemetery, just outside the reservation.

Letitia signed over her property to Andrew Carson in July 1884 and died on February 2, 1888, when she was about seventy years old. She was buried in a family cemetery on the property of Benjamin Stephens in Myrtle Creek. It is unknown what the relationship was between Letitia and the Stephens family, but her son Andrew would also be buried there after his death in 1922. Andrew Carson had no children, and all of Letitia's descendants trace their ancestry to her through Martha and the Lavadour family.

-

![]()

Letitia Carson's Homestead Claim, 1868.

Oregon State Archives -

![]()

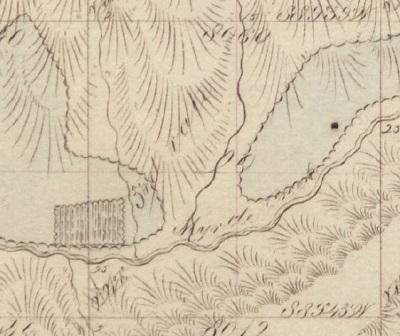

Detail of Carson's GLO claim record in Douglas County.

U.S. Bureau of Land Management -

![]()

Letitia's daughter Martha, her husband Narcisse Lavadour, and their son Nelson.

Letitia Carson Legacy Project, Joseph Lavadour

Related Entries

-

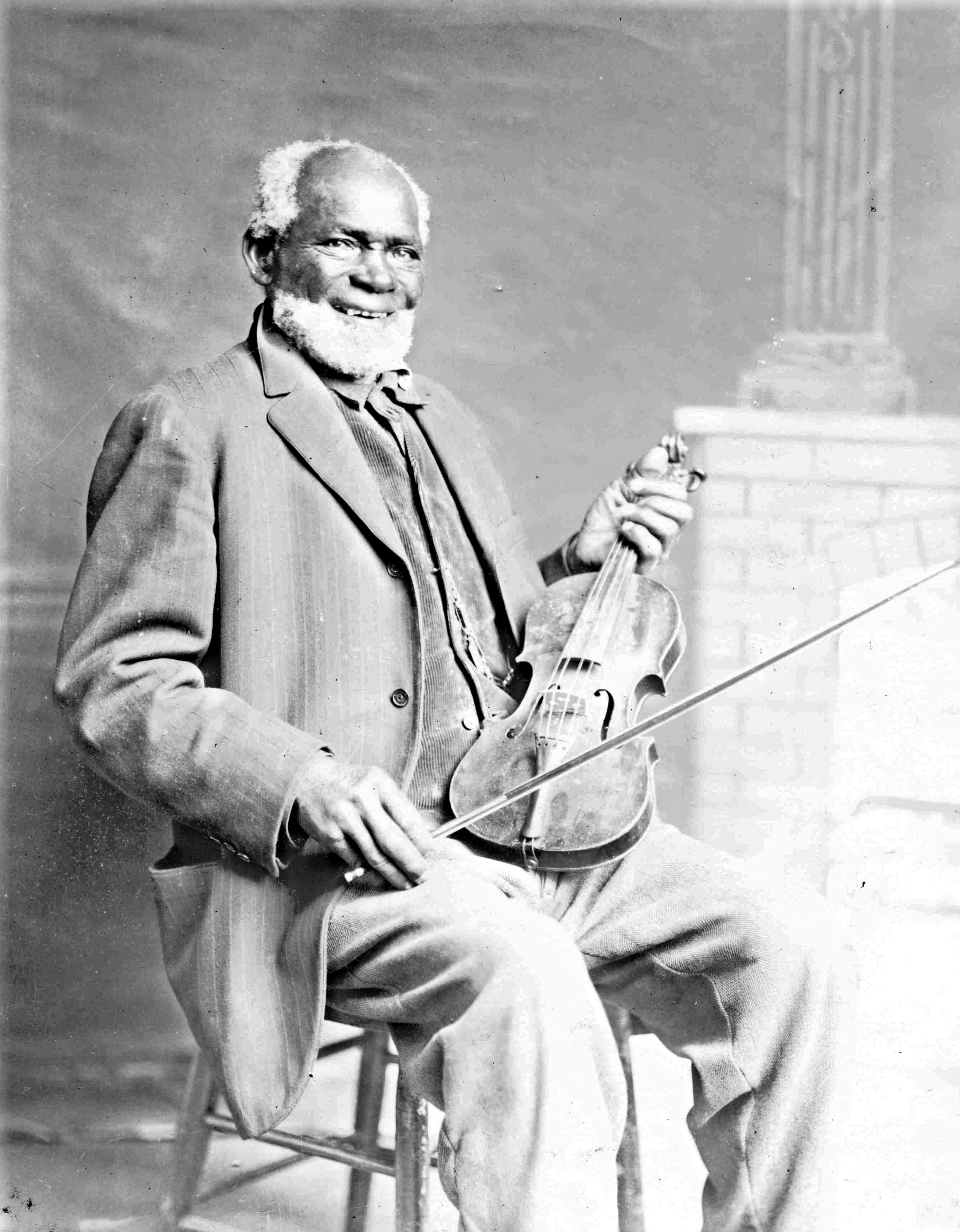

![Ben Johnson (1834–1901)]()

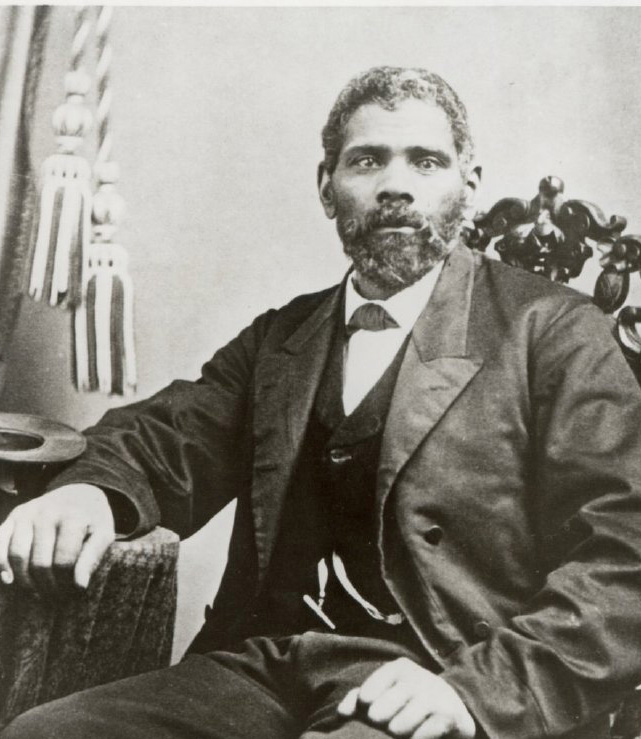

Ben Johnson (1834–1901)

Ben Johnson was a Black pioneer of Jackson County who came to Oregon as…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Holmes v. Ford]()

Holmes v. Ford

On April 16, 1852, a former slave named Robin Holmes filed suit against…

-

![Louis Southworth (1829–1917)]()

Louis Southworth (1829–1917)

Louis Southworth came to Oregon in 1853, a time that was less than hosp…

-

![Oregon Donation Land Law]()

Oregon Donation Land Law

When Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law in 1850, the legislat…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Letitia Carson Digital History Collection. Letitia Carson Legacy Project.

Zybach, Bob. "The Search for Letitia Carson, Part III." Umpqua Trapper 21.2 (Summer 2015).

"Shaping America's History: The Homestead Act, 2012." U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

Holman, Frederick V. “A Brief History of the Oregon Provisional Government and What Caused Its Formation.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 13. 2 (1912): 89–139.

"The Homestead Act." National Archives. Milestone Documents.

"Martha Jane Carson." Black in Oregon, 1840-1870. State of Oregon Archives, digital exhibit, 2016.

Vallance, Stephanie. “Letitia Carson in Court: African American Women, Property, and Wages in the Pacific Northwest." Portland State Univeristy Dissertations and Theses, 2021.