Only a few places in the Beaver State are named in reference to California, and Oregon Caves is one of them. Its earlier moniker, the Josephine County Caves, gradually faded from use after exploring parties sponsored by the San Francisco Examiner in 1891 and 1894 publicized their experiences at the site, just seven miles north of the California-Oregon state line. The Examiner referred to the "Oregon Caves" to distinguish it from caverns located in northern California. The name became official on July 12, 1909, when President William Howard Taft proclaimed 480 acres as Oregon Caves National Monument, one of the first of twenty tracts of federal land protected under the Antiquities Act passed by Congress three years earlier.

What makes the cave system unusual in comparison to others in western North America is the prevalence of marble (a more crystallized type of limestone). In addition to marble and limestone, igneous and sedimentary types are found both inside and outside the cave. The national monument is within a rugged area whose name Siskiyou generally applies to the mountain complex found north of the state line. This complex extends into northwest California as the Klamath Mountains; it is a distinct landscape characterized by diverse geology, botanical richness, and steep topography.

Mountain barriers and a lack of arable land made permanent settlement in the river valleys near Oregon Caves difficult. These limitations account for why the discovery of Oregon Caves—by Elijah Davidson of Williams—did not occur until 1874 and why the number of visitors in any year of the next four decades never exceeded a thousand. Commercial cave tours became viable in 1922, once a road funded by the Oregon State Highway Commission and the U.S. Forest Service reached the monument. The road also spurred the formation of "Caves City," later incorporated as Cave Junction in 1948, at its junction with the Redwood Highway.

With road access established, a public-private partnership was formed. Businessmen from Grants Pass financed lodging and staff to run a resort at Oregon Caves, while the federal government—first through the Forest Service and later the National Park Service—provided administrative oversight and infrastructure, including cave lighting, trails, and a water system. The private partner, the Oregon Caves Company, was inextricably linked to boosters in Josephine County. The most memorable expression of this relationship was in a group known as the Oregon Cavemen, whose appearance at community events included "adopting" U.S. presidents and movie stars and“imprisoning” women in a rolling cage during parades.

The Cavemen’s lighthearted pranks generated publicity for the monument at a time when the company began operating cave tours and building structures sheathed in the bark of native Port Orford-cedar. The structures included a chalet (1923, rebuilt in 1942), seven cottages (1926), a dormitory for cave guides (1927, additions in 1940 and 1972), and the magnificent six-story Chateau (1934) that spans a stream canyon and has a stream running through its dining room. It was one of the company's cave tours, followed by a stay in the Chateau in 1938, that inspired William Gruber to develop stereoscopic reels for what he eventually called the Viewmaster.

Public investment aimed at Oregon Caves is perhaps less conspicuous than commercial services for visitors, yet it is no less crucial to how the monument is experienced. Trails existed before the road opened in 1922; some were rebuilt and extended by the Civilian Conservation Corps from 1934 to 1941. The trail system not only makes it possible to walk the cave tour as a loop, but also provides a way to find some of the more than 400 plant species that grow within monument boundaries. Such diversity in a small area is remarkable, particularly when compared with places such as Crater Lake (fewer than 700 species thrive in Crater Lake National Park, which is more than a hundred times the size of Oregon Caves).

The trail through the "Marble Halls of Oregon," as poet Joaquin Miller first dubbed the cave, is scarcely a half-mile in length, but the geologic and faunal diversity along the route is exceptional. More than a dozen endemic animal species live in the cave, most of the micro-invertebrates. Nevertheless, it can be said of these creatures and the monument generally that nature excels in the least things.

-

![]()

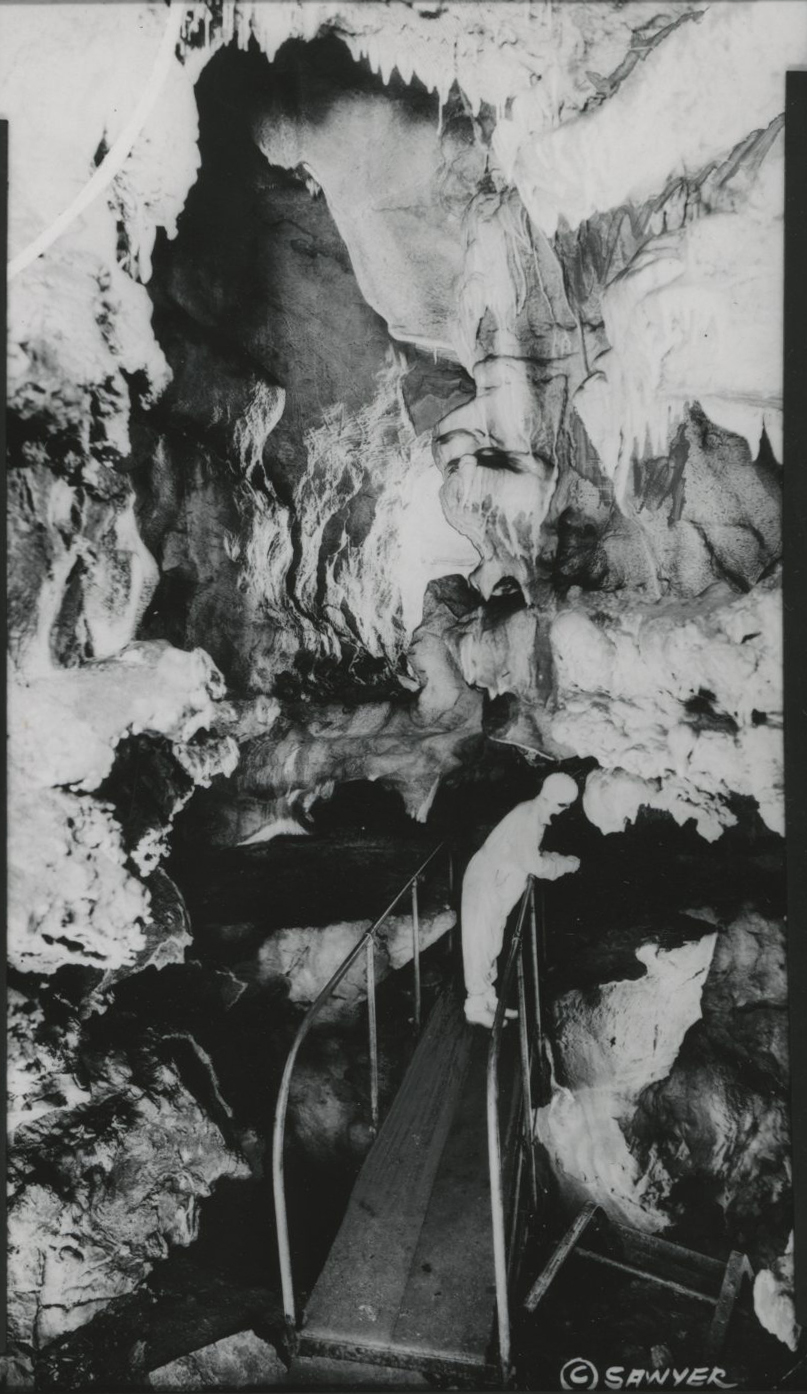

A steel stairway descends into the Oregon Caves, c.1925.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 003182

-

![]()

"Paradise Lost," fluted rock formation, Oregon Caves, 1931.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 005986

-

![]()

"Neptune's Daughter," Oregon Caves, 1923.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 000376

-

![]()

A person looks down into the River Styx, 1932.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 000367

-

![]()

"The Graveyard," Oregon Caves.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 000366

-

![]()

Entrance to the Oregon Caves, 2016.

Courtesy A.E. Platt

-

![]()

"The Chapel," Oregon Caves, 2016.

Courtesy A.E. Platt

-

![The pencil marks are preserved by a layer of calcite, and were still visible when this photo was taken in 2016.]()

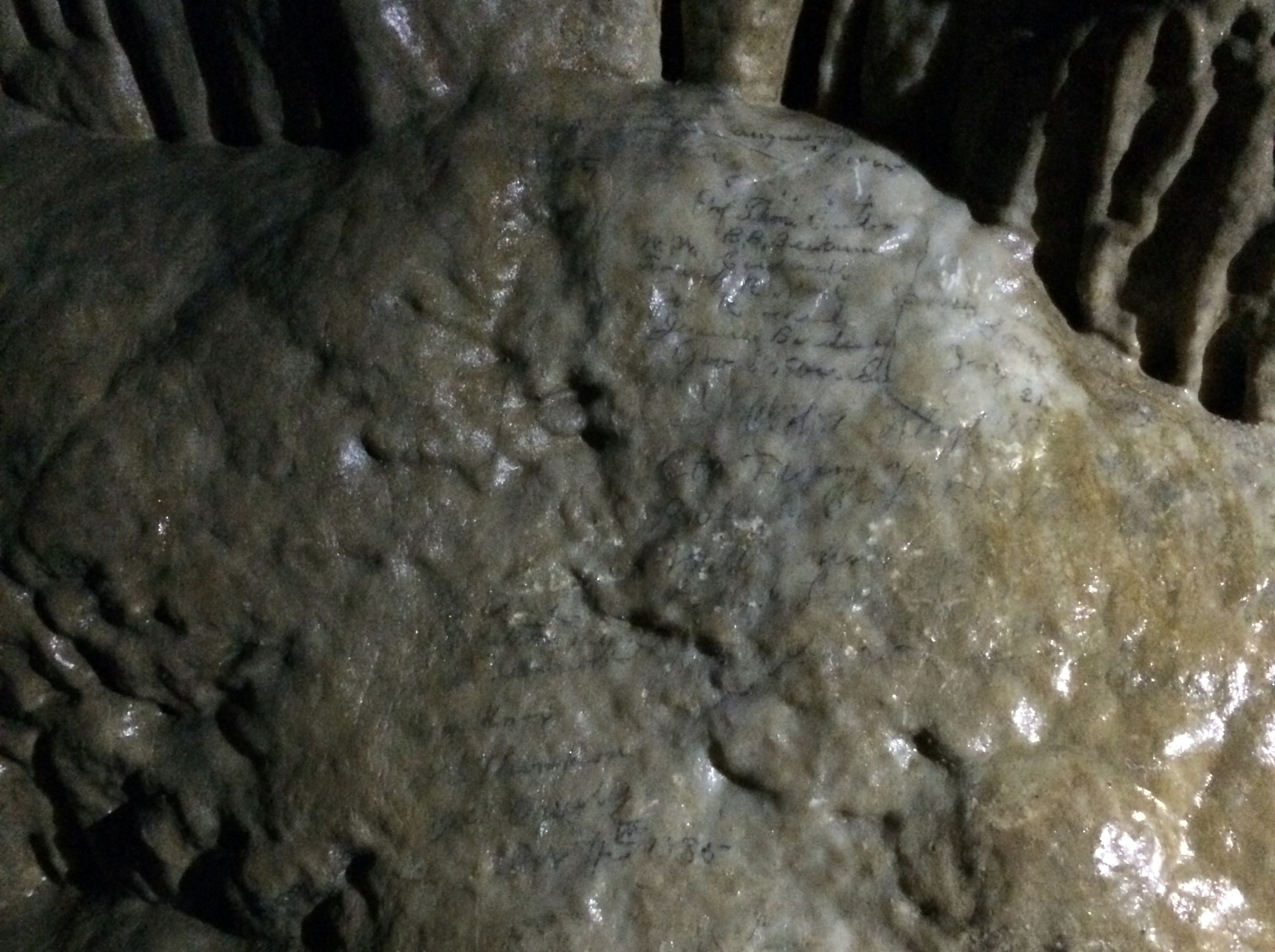

In 1883, geologist Thomas Condon and his students signed their names in the Oregon Caves. .

The pencil marks are preserved by a layer of calcite, and were still visible when this photo was taken in 2016. Courtesy A.E. Platt

Related Entries

-

![Grants Pass]()

Grants Pass

Located on the Rogue River about thirty miles northwest of Medford, Gra…

-

![Oregon Caves Chateau]()

Oregon Caves Chateau

The Oregon Caves Chateau was constructed between 1931 and 1934 as an ov…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Mark, Stephen R. Domain of the Cavemen: A Historic Resource Study of Oregon Caves National Monument. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 2006.

Roth, John. "Why So Many Siskiyou Plants?" Nature Notes from Crater Lake 31 (2000), 17-21.

Working, Russell. "Clan of the Cavemen," Table Rock Sentinel 12:3 (Summer 1992), 2-13.