The Oregon School for the Blind, also known as the Oregon Institute for the Blind and the Oregon State School for the Blind, was a publicly funded residential school in Salem from 1872 to 2009. During its 136-year history, its staff developed innovative programs and directed the education of generations of vision-impaired students in Oregon.

The Oregon legislature funded what became known as the Oregon School for the Blind (OSB) in 1872, and it opened the same year with two students under the care of William and Marie Nesbitt; the first classes were held in their home. Nellie Simpson, who was blind, was their teacher. By the end of the first term, five students, aged twelve to thirty-two, were enrolled. Within two years, the school and its eight students had moved to 13th Street, between Court and Chemeketa.

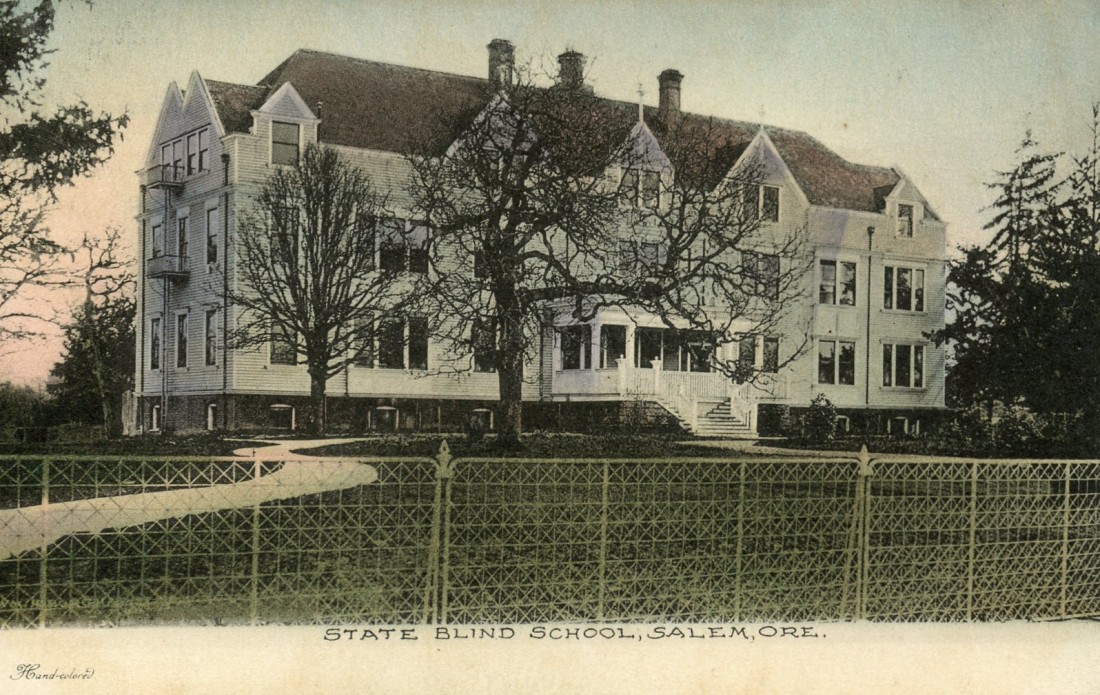

In 1883, school superintendent Rev. J. H. Babcock moved the school and its twenty students to the Snowden Building on 12th and Ferry Streets. By 1895, the school had moved to its final location: a seven-acre campus on Church and Mission Streets SE, with twenty-nine students. A large two-story brick building—designed by architects William Ellicott and Edgar Lazarus—housed administrative offices, a chapel, classrooms, and residential dorms.

Residential schools for the blind throughout the United States during the nineteenth century largely followed the philosophy of reformer Samuel Gridley Howe (1801–1876), who characterized blind students as capable learners rather than as unfortunates who should be pitied and protected. Rev. Babcock agreed, writing in 1876 that the Oregon School for the Blind “is not an asylum, nor a hospital, nor a poorhouse but a school.” His objective was to put students “on equal footing” by giving them opportunities to study the “ordinary branches of learning” while also receiving specialized training that fostered independence.

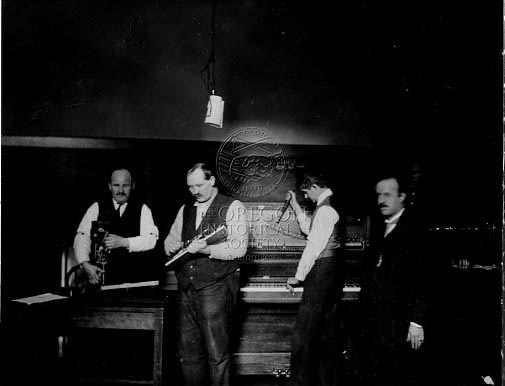

During the first half of the twentieth century, OSB students from throughout Oregon, some as young as six years old, were under the care of house mothers for nine months of the year. During the 1930s, enrollment reached seventy-four students who received instruction in academics, music, physical education, and “industrial skills” such as basket weaving and piano tuning. There were classes in mobility training, life skills, and Braille, and the school had a drama club, wrestling team, and an annual outdoor education week at Camp Magruder on the Oregon Coast. In collaboration with the Lions Club, OSB hosted an annual week-long conference for parents.

The school provided opportunities for social growth, as well, and stressed that “moral training” should not be neglected. “It is expected,” the school’s rules and regulations directed, “that the pupils will attend public worship at least once on Sunday, at such places as they or their guardians may prefer.” Teachers also addressed etiquette and social mores.

As enrollment grew during the twentieth century, the OSB campus expanded. Howard Hall, a boys dormitory designed by architect John V. Bennes, was built in 1923; a second dormitory, Irvine Hall, was built in 1934. During the 1940s, housing for the superintendent and the school principal were constructed, and a running track with a hand guardrail was installed. The original administration and classroom building was torn down in 1956, replaced by one with classrooms, offices, an auditorium, a dining hall, and a health service facility. A sensory rock garden and a gymnasium with a swimming pool and bowling alley were added during the 1950s.

During the mid-twentieth century, OSB experienced a boom in enrollment, partly because of a national epidemic of retinopathy of prematurity, or ROP (formerly called retrolental fibroplasia). Many premature babies had received unmonitored oxygen supplements as treatment, and low oxygen levels had caused their retinal vessels to dilate, causing edema and hemorrhaging. OSB served this population with experienced staff, specialized materials, and equipment and offered weeklong institutes for parents of children with ROP. The Oregon Lions Club Auxiliary sponsored clinics at the school during the 1940s and 1950s for parents with children who had ROP, and parents were offered free room and board for six-day sessions where they learned how to teach their visually impaired children. Careful oxygen monitoring eventually helped eliminate many cases of ROP.

During the 1940s, OSB administrators and others designed what was called the Oregon Plan, an approach unique in the nation that called for cooperation between OSB and public schools. One outcome was a phase-out of traditional high school classes at OSB by the late 1940s and a focus on teaching students Braille and other skills to prepare them for public schools. Those students who had challenges or needs that could not be met by public schools remained at OSB. The program had success integrating older students into their neighborhood schools.

By the mid-1960s, OSB was among the first residential schools for the blind in the nation to study and implement programs exclusively for students with multiple disabilities—a particularly vulnerable group with respect to access to quality education. That population comprised a significant percentage of OSB’s full-time students until the school closed in 2009. In some years, a field service unit traveled to rural areas to conduct weekend workshops, and OSB participated in statewide in-service teacher training through the 2000s.

In 1975, Congress passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which mandated that students with disabilities be educated in the “least restrictive environment” possible. A national debate wrestled over what a “least restrictive environment” looked like and how it applied to schools like OSB. Citing funding issues and concerns over OSB’s residential program, the Oregon legislature considered closing the school in 1978—and repeatedly thereafter; but each attempt was met with strong opposition from members of the OSB community who worried that public schools could not accommodate the complex needs of their children.

In June 2009, the legislature voted to close the school and to mainstream blind and low-vision students into local public schools exclusively. The twenty-four students attending OSB were expected to transfer to their local schools that fall. In 2010, the school’s property was sold to the Salem Hospital, and the buildings, except Howard Hall, were razed in 2011. Howard Hall was demolished in 2015. The former schoolground now has a multisensory Let’s All Play Place park and parking for Salem Hospital.

-

![]()

Oregon School for the Blind.

Courtesy Willamette Heritage Center, WHC 2011.006.0689 -

![]()

Graduating Class of the Blind School, Salem, 1920.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 0156N185

-

![]()

Oregon Institute for the Blind, 12th and Ferry, Salem, 1893.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 0177G003

-

![]()

Oregon State School for the Blind.

Angelus Studio photographs, 1880s-1940s, University of Oregon. "PH037_b200_48111" Oregon Digital. -

![]()

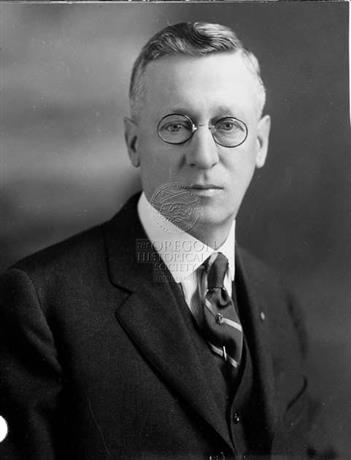

J. W. Howard, State School for the Blind, 1922.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 0158N245

-

![]()

Nellie Dickhart, 1921.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 0159N049

-

![]()

Piano tuning class at the School for the Blind.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 004033

-

![Financed by the Public Works Administration.]()

Dormitory at the State School for the Blind, 1937.

Financed by the Public Works Administration. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 006574

-

![]()

Howard Hall, Oregon State School for the Blind.

Building Oregon, University of Oregon. "Howard Hall, Oregon State School for the Blind (Salem, Oregon)" Oregon Digital.

Related Entries

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Oregon School for the Blind Oral History Project, Willamette Heritage Center.

Koestler, Frances A. The Unseen Minority: A Social History of Blindness in the United States. New York: AFB Press, American Foundation for the Blind, 1976.

Ross, Ishbel. Journey Into Light: The Story of the Education of the Blind. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1951.

Satchwell, Wayne, Mildred Sanders Gibbens, and Oregon Council of the Blind. The Status of the Blind in the State of Oregon. Salem: Oregon Council of the Blind, 1977.

Oregon State Board of Control. Information for Parents and Friends of Blind and Partially Blind Children: Oregon State School for the Blind. Salem: State Printing Department, 1927.

Putnam, Rex, Kenneth C. Swan, and Walter Dry. Report of the Temporary Board for the Investigation and Planning of Education for Blind Children in the Public Schools of Oregon. Salem: State of Oregon, 1951.

Rigby, Mary E., and Charles C. Woodcock. Development of a Residential Education Program for Emotionally Deprived Pseudo-Retarded Blind Children Vol. I, Final Report. Salem: State of Oregon, April 1969.

Lowenfeld, Berthold. “The Oregon Plan.” Outlook for the Blind 40 (1946): 67-75.

McIntire, Jonathan C. “The Future Role of Residential Schools for Visually Impaired Students.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 79.4 (1985): 161-164.

Miller, William H. “The Role of Residential Schools for the Blind in Educating Visually Impaired Students.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 79.4 (1985): 160.

Orlansky, Michael D. “Education of Visually Impaired Children in the U.S.A.: Current Issues in Service Delivery.” The Exceptional Child 29.1 (1982): 13-20.

Cowling, Freda. “Blind School Lists Dates: Parents to Attend Annual Institute.” The Sunday Oregonian, May 29, 1955.

Treveaven, Mike. “Oregon Programs Excite New Chief of Blind School.” Oregonian, September 3, 1972.

“State to Weigh Cost Effectiveness on School for Blind.” Oregonian, Jan 15, 1978.

Durbin, Kathie. “State school for the Blind Faces Identity Dilemma.” Oregonian, 7 Feb 1979.

Collins, Huntly. “By State Board: Closing School for Blind Opposed.” Oregonian, May 23, 1981.

Durbin, Kathie. “Plan to Close Blind School to be Aired.” Oregonian, May 5, 1983.

Durbin, Kathie. “Blind People Oppose Closure of School.” Oregonian, May 31, 1984.

Durbin, Kathie. “Panel Asks Restoration of Funding.” Oregonian, Dec 14, 1984.

Hammond, Betsy. “Vote Closes School for Blind.” Oregonian, June 11, 2009.

“O.S.S.B Beginnings—An Unusual Era.” Supplement to The Capital Journal and Oregon Statesman, February 24, 1973.