Described as the “case of the century” and the “biggest case on the planet,” Juliana v. United States (August 12, 2015) was a leading U.S. constitutional climate case. The historic case ended on March 24, 2025, when the U.S. Supreme Court opted not to review a lower court's decision to dismiss the case on procedural grounds.

Juliana v. United States represents a bold and innovative approach to the effort to preserve a livable climate. Rather than attempting to address the government's role in causing and accelerating the collapse of the climate system through compartmentalized statutory environmental laws, such as the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act or civil tort claims, Juliana invoked the judiciary's constitutional obligation to hold the executive branch of the government accountable when its actions destroy natural resources essential to life.

Our Children's Trust, a public interest non-profit law firm basin in Eugene, Oregon, filed the case in the United States District Court for the District of Oregon, on behalf of Kelsey Juliana and twenty other plaintiffs, ranging in ages from fourteen to twenty-five. The case built on the work of professor Mary Wood of the University of Oregon School of Law, who conceived of the Atmospheric Trust Litigation as a fundamental-rights-based strategy for enforcing the legal duty of the U.S. government and other governments to preserve a livable atmosphere for current and future generations.

Hailing from Oregon, Hawaii, Alaska, and eight other states, the young people who brought the suit asserted that the U.S. government had violated their constitutional rights to life, liberty, and property guaranteed by the Due Process Clause and had breached constitutional public trust obligations by promoting the production and use of fossil fuels that destabilize the climate. Under the public trust doctrine, which is recognized in federal and state law and the laws of other countries, the government holds natural resources—that are essential for life and liberty—in trust for the people. Therefore, the plaintiffs claimed, it has a duty to preserve those resources for present and future generations.

The youth alleged that "for over fifty years, the United States of America has known that [CO2] pollution from burning fossil fuels was causing global warming and dangerous climate change, and that continuing to burn fossil fuels would destabilize the climate system on which present and future generations of our nation depend for their wellbeing and survival.” Further, the defendants—the President of the United States, the U.S. government, and several federal agencies—knew that the harmful effects of their actions would “significantly endanger Plaintiffs, with the damage persisting for millennia. Despite this knowledge, Defendants continued their policies and practices of allowing the exploitation of fossil fuels.” The defendants, the plaintiffs charged, had “acted with deliberate indifference to the peril they knowingly created.”

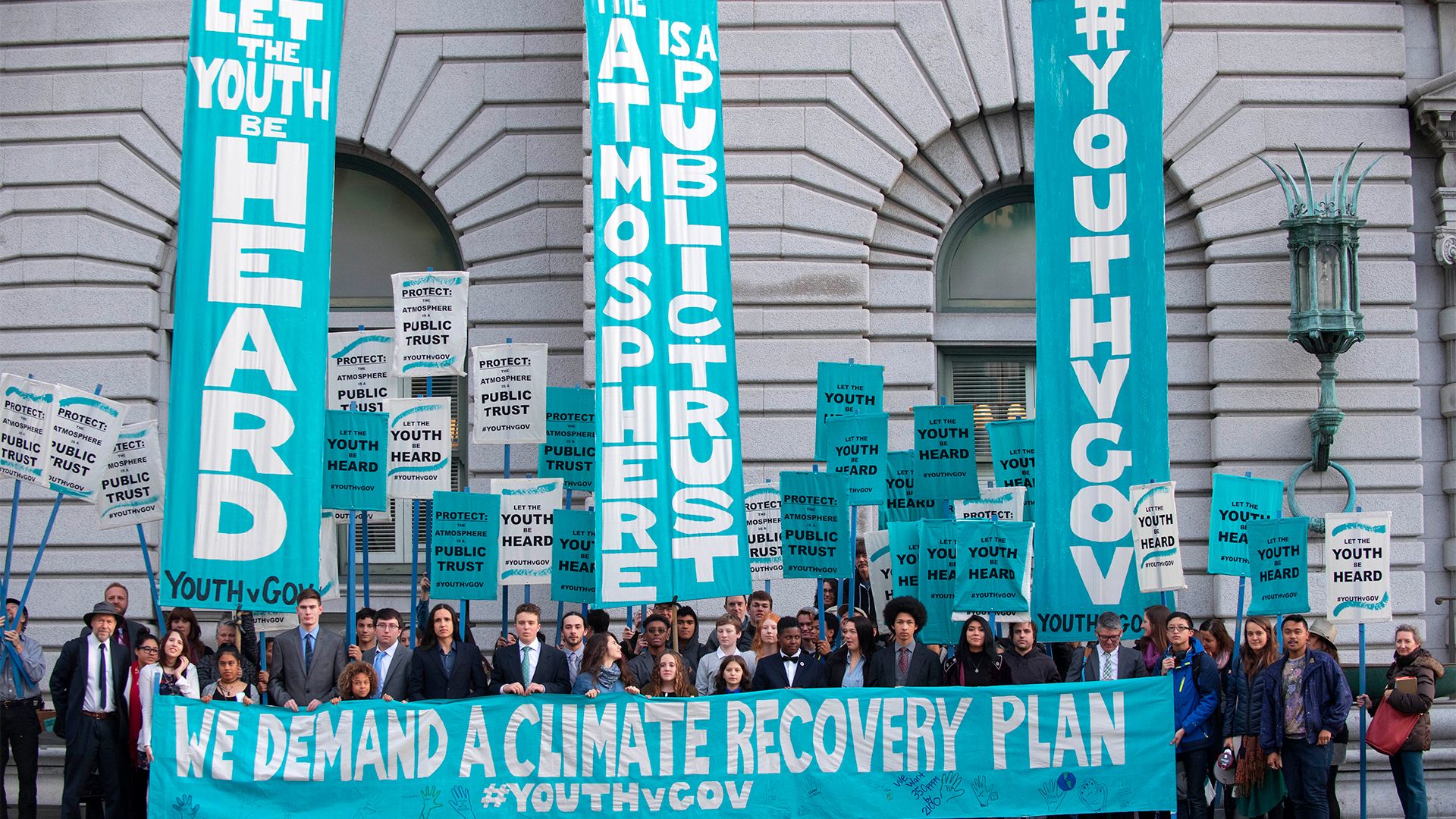

Representing the diversity of American youth affected by the climate crisis—including Black, Indigenous, white, biracial, and LGBTQ youth—the plaintiffs were activists, students, artists, musicians, and farmers. Threatened by the climate catastrophe they are inheriting, they asked the District Court to declare their right to a climate that can sustain life. They also asked the court to order the federal government to develop an enforceable remedial plan to reduce carbon emissions and remove carbon from the atmosphere at a rate called for by the best available science.

The government moved to have the case dismissed, arguing that the “Constitution does not provide judicial remedies for every social and economic ill.” On November 10, 2016, however, Judge Aiken issued a historic opinion denying the motions to dismiss the case and allowing the case to proceed to trial. Her opinion marked the first time a court had recognized that a “climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.” The judge also held that government actions that impair the climate system violate the Due Process Clause, which "safeguards fundamental rights that are implicit in the concept of ordered liberty or deeply rooted in this Nation's history and tradition." She found that the right to a livable atmosphere meets both of these standards.

Instead of proceeding to trial, motions and appeals filed by the United States stalled the case, including a successful appeal of Judge Aiken’s opinion. On January 17, 2020, a divided panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the case. The majority ruled that the courts lack the authority to order the federal government to develop a plan to decarbonize the atmosphere, while also recognizing that the plaintiffs presented compelling evidence that the “unprecedented rise [in CO2 levels] stems from fossil fuel combustion and will wreak havoc on the Earth’s climate if unchecked” and “the federal government has long promoted fossil fuel use despite knowing that it can cause catastrophic climate change.” The opinion was based on the majority’s conclusion that the U.S. Constitution dedicates these types of complex policy decisions exclusively to the political branches of government, notwithstanding the majority’s recognition that those branches of government may be "hasten[ing] an environmental apocalypse" in knowing disregard for the plaintiffs’ fundamental rights.

In dissent, U.S. District Court Judge Josephine Staton reasoned that when confronted by “an existential threat" to the continuation of the United States that "has not only gone unremedied but is actively backed by the government,” the court has the authority to order the government to take action to avert the threat. The “most basic structural principle embedded in our system of ordered liberty,” Judge Staton wrote, "is that the Constitution prohibits willful government action that causes or contributes to the Nation’s destruction.”

In response to the court’s dismissal of their case in 2020, the plaintiffs amended their claims to remove their request that the federal government develop a plan to address climate change and limit the relief to a declaration that the government's fossil-fuel energy policies violate the youths’ fundamental rights to life, liberty, and property. In May 2024, the U.S. Court of Appeals granted the government's motion to dismiss the case on procedural grounds, and in May 2025, the U.S. Supreme Court denied the plaintiffs' petition for certiorari asking the Court to review the May 2024 order.

The legal framework conceived of by Professor Mary Wood and asserted by the twenty-one youth plaintiffs in Juliana v. United States inspired a worldwide campaign of Atmospheric Trust Litigation. Currently, more than sixty youth-led climate lawsuits have been filed worldwide, leading to youth victories in cases such as the June 2024 settlement in Navahine v. Hawai‘i Department of Transportation and the Montana Supreme Court’s order in Held v. State of Montana (December 18, 2024), which affirmed the trial court’s ruling in favor of the youth plaintiffs.

-

![]()

Plaintiffs, Juliana v. United States, 2016.

Courtesy Youth v. Gov (film) press, Netflix -

![]()

Plaintiffs in Juliana v. United States.

Courtesy Youth v. Gov (film) press, Netflix

Related Entries

-

![Climate Change in Oregon]()

Climate Change in Oregon

Within a few hundred miles in Oregon, you can see snowy volcanoes, parc…

-

![Oregon Climate Change Research Institute]()

Oregon Climate Change Research Institute

The Oregon Climate Change Research Institute was established in 2007 to…

-

![Oregon Global Warming Commission]()

Oregon Global Warming Commission

The Oregon legislature created the Oregon Global Warming Commission in …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Juliana v. United States, 217 F. Supp. 3d 1224 (D. Or. 2016).

Juliana v. United States, 947 F.3d 1159 (9th Cir. 2020).

Wood, Mary Christina. Nature’s Trust: Environmental Law for a New Ecological Age. Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013.

"Juliana v. United States." Our Children’s Trust.

Youth v. Gov: the Film. Vulcan Productions, 2021. Video.

Juliana v. United States. Climate Change Litigation Databases. (Case documents; case chronology)

The author thanks Samantha Blount, Student Fellow, Environmental and Natural Resources Law Center, University of Oregon School of Law, JD 2022, and Michelle Smith, Research Associate, Environmental and Natural Resources Law Center, University of Oregon School of Law, for significant contributions to this entry.