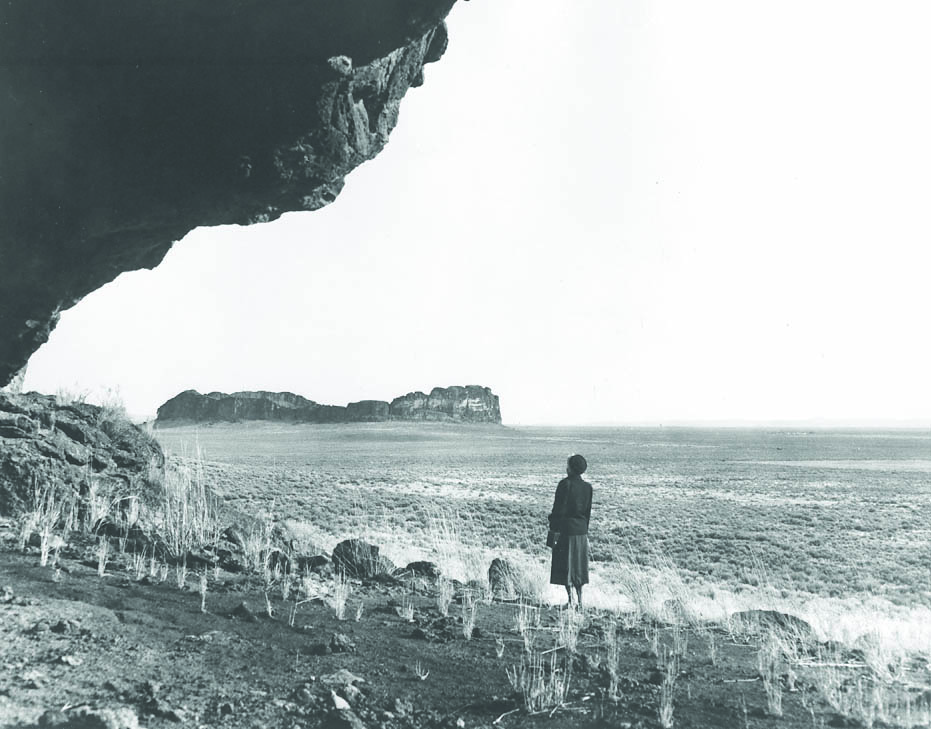

The town of Fort Rock is an unincorporated community in northern Lake County built atop a wide sagebrush-covered, ice-age lakebed. The first homestead in Fort Rock Valley was claimed in 1905, followed by a land rush of would-be farmers arriving from as far away as the East Coast and Europe. The first store in the town of Fort Rock opened in 1908, and a post office soon followed. By 1910, about twelve hundred people lived in the surrounding area on dry-farm homestead claims. Those years of growth ended by 1917–1920, when the town’s survival appeared to be less than a sure thing. In 2023, Fort Rock is the only town that survived among the several dozen hamlets founded during southeastern Oregon’s early twentieth-century dry-farm homestead boom.

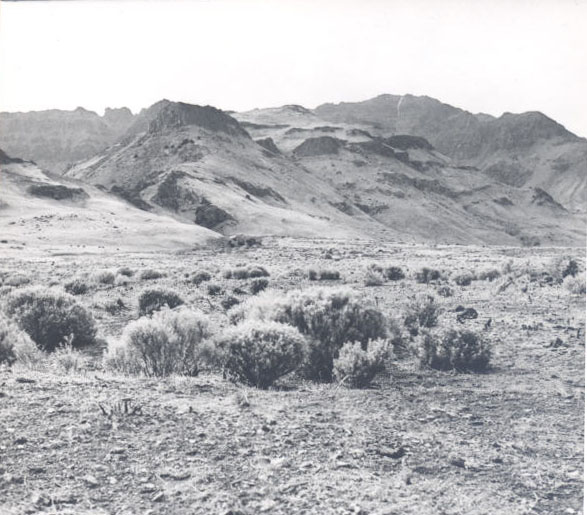

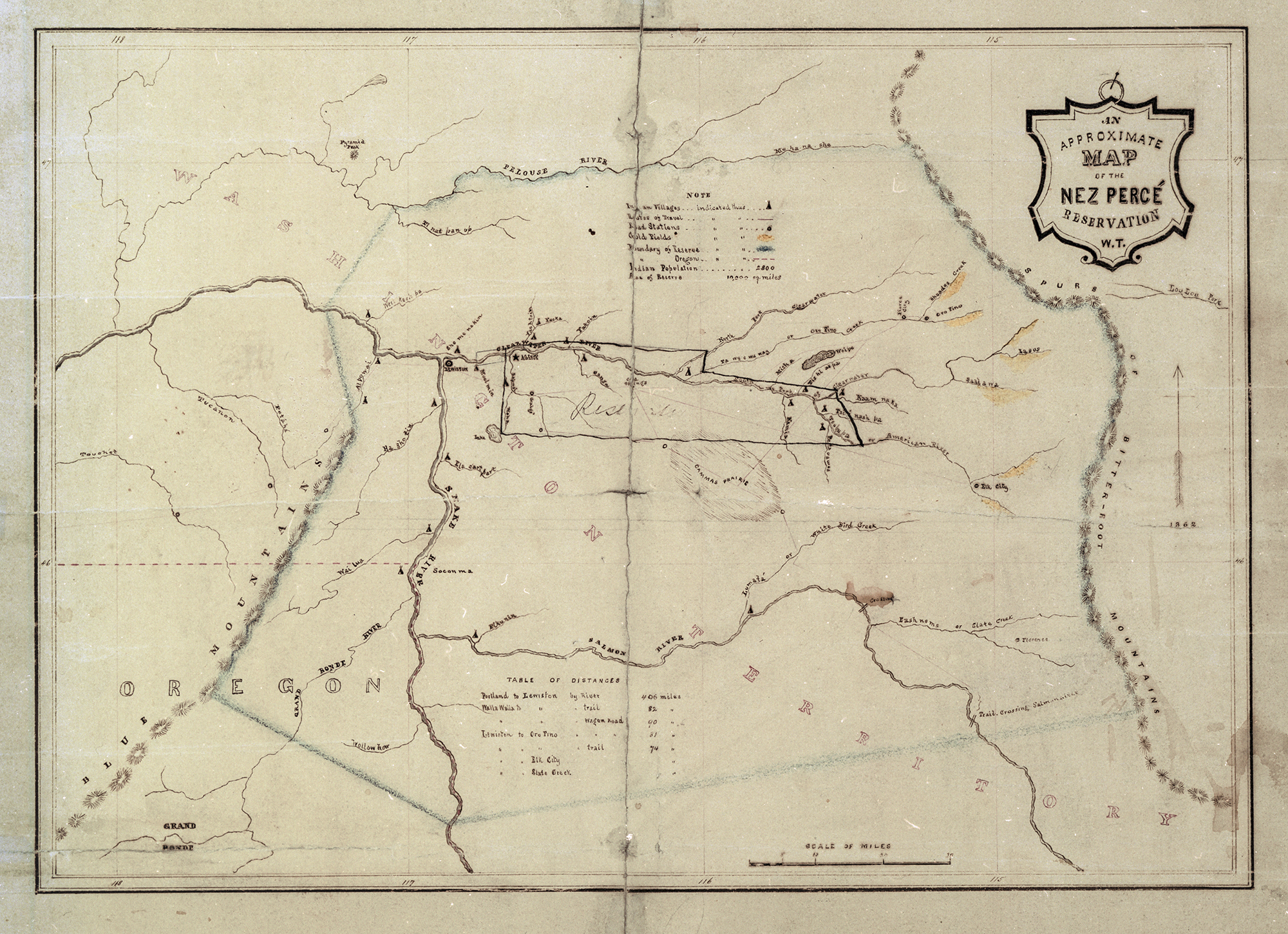

The Fort Rock Valley is in the homeland of Northern Paiute people. A series of treaties negotiated by the federal government relocated most Northern Paiute to reservations, and by the end of the nineteenth century the land was open to white settlement. The region became part of a land rush and benefited from an optimistic belief in the agricultural principles of dry farming in areas of very low rainfall. During the first decade of the twentieth century, the dry-farming movement attracted thousands of homesteaders to Fort Rock Valley and other arid land in the American West, including Oregon’s High Desert. Further stimulating the dry-farming boom was the passage in 1909 of the Enlarged Homestead Act, which doubled the amount of so-called free land that a homesteader could obtain, from 160 acres to 320 acres.

According to oral historian Barbara Allen, early homesteaders in Fort Rock Valley were drawn to the area by free land, clean air, and low crime. Located along what was once the major wagon road between Prineville and Silver Lake, the community of Fort Rock served the area’s permanent population and the tourists who visited nearby Fort Rock Cave, an ice-age archaeological site that was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961. It was a good location for a town. Water was only twenty to fifty feet below the surface of the lakebed, and wells could be hand-dug or drilled in a short amount of time by pumping the water upward with one of the many Aermotor windmills that dotted the valley.

Fort Rock also straddled an inconvenient offset of 312.2 feet for the valley’s main wagon road, which ran along section lines. The awkward right-left turn on what would be the initial route of the Fremont Highway (now Cabin Lake Road/County Road 5-13) slowed horse-drawn wagon traffic to a walk in the only S-curve between the larger town of Silver Lake seventeen miles to the south and the hamlet of Millican eighty-seven miles to the north. A few businesses, including two saloons and a livery stable, were built on the S-curve, along with a blacksmith shop and a hotel.

The Ladies Aid of the community of Fort Rock was chartered in 1909, and a cemetery association formed in 1910. Land locators operating from the local hotel helped newcomers find land that was available for homestead claims, and from 1913 to 1918 the weekly Fort Rock Times published official homestead-claim notices, as well as news of local doings. Dances were a popular diversion, as was baseball, horse racing, pie socials, and debates and speeches. Summer picnics, sometimes held in the cool temperatures of South Ice Cave, Derrick Cave, or Crack in the Ground, were community events.

In 1912, a U.S. Forest Service ranger rented a small house in town. In order to communicate with his supervisor’s office in Bend, he brought phone service to Fort Rock in 1914 by hooking wire fences together along the nine miles of road from Fort Rock north to Cabin Lake Ranger Station. The line was later expanded to serve families and businesses in the area, including other homestead communities such as Arrow, Connelly, Fremont, Fleetwood, and Wastina. Most of those communities only had a post office—many of them a slotted box mounted inside a homesteader’s cabin—and a one-room schoolhouse.

Above-average rainfall produced decent rye crops between 1907 and 1916, but the summer weather brought little or no rain. More problematic for grain-farming homesteaders were the sporadic plagues of jackrabbits and killing summertime frosts. By 1916, people had begun to leave Fort Rock, attracted by work at the sawmills in Bend and the shipyards in Portland and Seattle.

During the 1930s, the federal government concluded that it had been a mistake to open marginal lands to dry-farm homesteading. The Fort Rock Land Utilization Project purchased abandoned homesteads and returned the land to grazing, which was administered by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. By 1950, the area’s population had fallen to three hundred people. Power lines reached Fort Rock in 1955, making it feasible to pump-irrigate from deep wells that tapped aquifers beneath the desert floor. Irrigation from that source now supports the extensive acres of alfalfa that turn much of the valley green each year.

In the twenty-first century, alfalfa production, cattle ranching, and tourism have supported Fort Rock. In 2023, the town of an estimated 134 people had a restaurant and bar, a Grange, two RV parks, a community church, and an outdoor Homestead Museum that tells the history of the area’s dry-farm homestead boom.

-

![]()

Fort Rock Homestead Museum, Fort Rock, 2019.

Courtesy Oregon State Archives -

![]()

Aerial view of Fort Rock and town, 1970.

OSU Special Collections & Archives Research Center, Oregon State University. "Aerial view of Fort Rock, Oregon, June 1970" Oregon Digital. -

![]()

Homestead building, Fort Rock.

Courtesy Oregon State Archives -

![]()

A building at the Fort Rock Museum, 2019.

Courtesy Oregon State University

Related Entries

-

![Crack in the Ground]()

Crack in the Ground

Crack in the Ground is just that, a gaping fracture of tectonic origin …

-

![Fort Rock Cave]()

Fort Rock Cave

Fort Rock Cave is located in a small volcanic butte approximately half …

-

![Fort Rock Sandals]()

Fort Rock Sandals

Fort Rock sandals are a distinctive type of ancient fiber footwear foun…

-

![High Desert]()

High Desert

Oregon’s High Desert is a place apart, an inescapable reality of physic…

-

![National Reclamation Act (1902)]()

National Reclamation Act (1902)

When Congress passed the National Reclamation Act in 1902, the measure …

-

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Allen, Barbara Homesteading the High Desert. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987.

Jackman, E. R. and R. A. Long. The Oregon Desert. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1964.