Minoru Yasui was born in Hood River on October 16, 1916, the third son of Japanese immigrants Shidzuyo and Masuo Yasui. In 1939, Yasui became one of the first Japanese Americans to graduate from the University of Oregon School of Law and the first Japanese American member of the Oregon Bar. He made national history by challenging the constitutionality of the military curfew imposed on Japanese American citizens in World War II.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Yasui, who had been working for the Japanese Consulate in Chicago, resigned his position and returned to Oregon. He expected to be called up for service since he had been commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Infantry Reserve, but the army refused to accept him for active duty.

During World War II, the loyalty of American citizens of Japanese descent was challenged. Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command argued that military necessity justified the imprisonment of Japanese aliens and Japanese Americans alike, even though other authorities believed that there was no need to fear the Japanese in the United States.

Following the signing of Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, General DeWitt issued a series of military orders, including a curfew that ordered all German nationals, Italian nationals, and persons of Japanese ancestry to remain in their homes between the hours of 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. Violating the curfew was a criminal offense under federal law.

Yasui believed that the military orders were unconstitutional as applied to U.S. citizens and that the constitutional rights of Japanese Americans would be upheld by the courts. On March 28, 1942, he walked the streets of Portland to intentionally violate the military curfew, which eventually led to his arrest. At the age of twenty-five, Yasui put his professional career and his personal liberty on the line for justice.

At Yasui's trial in federal court, his attorney argued that the 14th and 5th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the civil rights of citizens to equal protection and due process of law. The government argued that Japanese racial characteristics naturally prompted them to be loyal to Japan and to betray the United States, regardless of citizenship. The government also argued that it has special powers in time of war.

In his finding, Judge Alger Fee ruled that the military orders and attendant laws were unconstitutional as applied to American citizens. He also ruled that Yasui, having worked for the Japanese Consulate, had abrogated his U.S. citizenship and, therefore, was an enemy alien to whom the military curfew did apply. Yasui was sentenced to one year in prison and a fine of $5,000.

Undeterred, Yasui appealed his case. He spent nine months in solitary confinement at the Multnomah County jail as his case wound its way from the lower courts to the U.S. Supreme Court. On June 21, 1943, the Supreme Court ruled that while Yasui did not lose his U.S. citizenship, his rights could be overridden—based on race—in time of war. The court allowed, through "judicial notice"—that is, not having to prove facts that are regarded as self-evident—that Japanese racial characteristics, their religion, and their practices (such as martial arts) made them likely to betray the United States and to have allegiance to Japan. Japanese Americans, therefore, were judged to be a military threat.

Having already served most of his jail term, Yasui was sent to Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho, where he stayed until he was released in mid-1944. He moved to Denver, where he established a law practice. He continued to pursue his vision and to fight for civil rights, both as a lawyer and later as executive director of the Commission on Community Relations, which addressed race relations and other social issues. In 1976, Yasui worked on a Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) committee on the wrongful imprisonment of Japanese Americans in World War II; he was named chair of that committee in 1981.

In 1982, Yasui began to explore the possibility of reopening his World War II case. He learned that material had been unearthed at the National Archives that showed the curfew was not based on military necessity but on racial discrimination. Yasui's petition, filed on February 1, 1983, requested that the district court declare the curfew order unconstitutional and that the court throw out his indictment and conviction. The court vacated his indictment and conviction but refused to allow an evidentiary hearing to rule on the charges of racial discrimination.

Yasui appealed the district court decision, but the case was not resolved before his death on November 12, 1986. Two weeks later, the government moved to dismiss Yasui's appeal as moot, which would prevent the full evidentiary hearing on the government's alleged discriminatory actions. Those actions had led to the imprisonment of 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry, 70 percent of whom were U.S. citizens.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals granted the government's motion, which was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a few short sentences, the Supreme Court ruled that the appeal was moot, affirmed the motion to dismiss, and dashed the hopes of many. The Yasui case was over.

Minoru Yasui's final return to Oregon occurred forty years after he had left, when his ashes were buried beneath a pair of giant cedars, as he had requested, beside the memorial marker for his parents at Idlewild Cemetery in Hood River. "It was my belief," Yasui once said, "that no military authority has the right to subject any United States citizen to any requirement that does not equally apply to all other U.S. citizens. If we believe in America, if we believe in equality and democracy, if we believe in law and justice, then each of us, when we see or believe errors are being made, has an obligation to make every effort to correct them."

In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor, to Yasui for challenging the incarceration of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during World War II and for his leadership in civil and human rights. He is the first Oregonian to receive that Medal.

In 2016, Minoru Yasui’s centennial, the Oregon Legislature unanimously enacted a statute designating March 28 as Minoru Yasui Day in perpetuity. The commemorate recognizes the date in 1942 when Yasui deliberately challenged the military curfew pursuant to Executive Order 9066 to bring his constitutional test case.

-

![]()

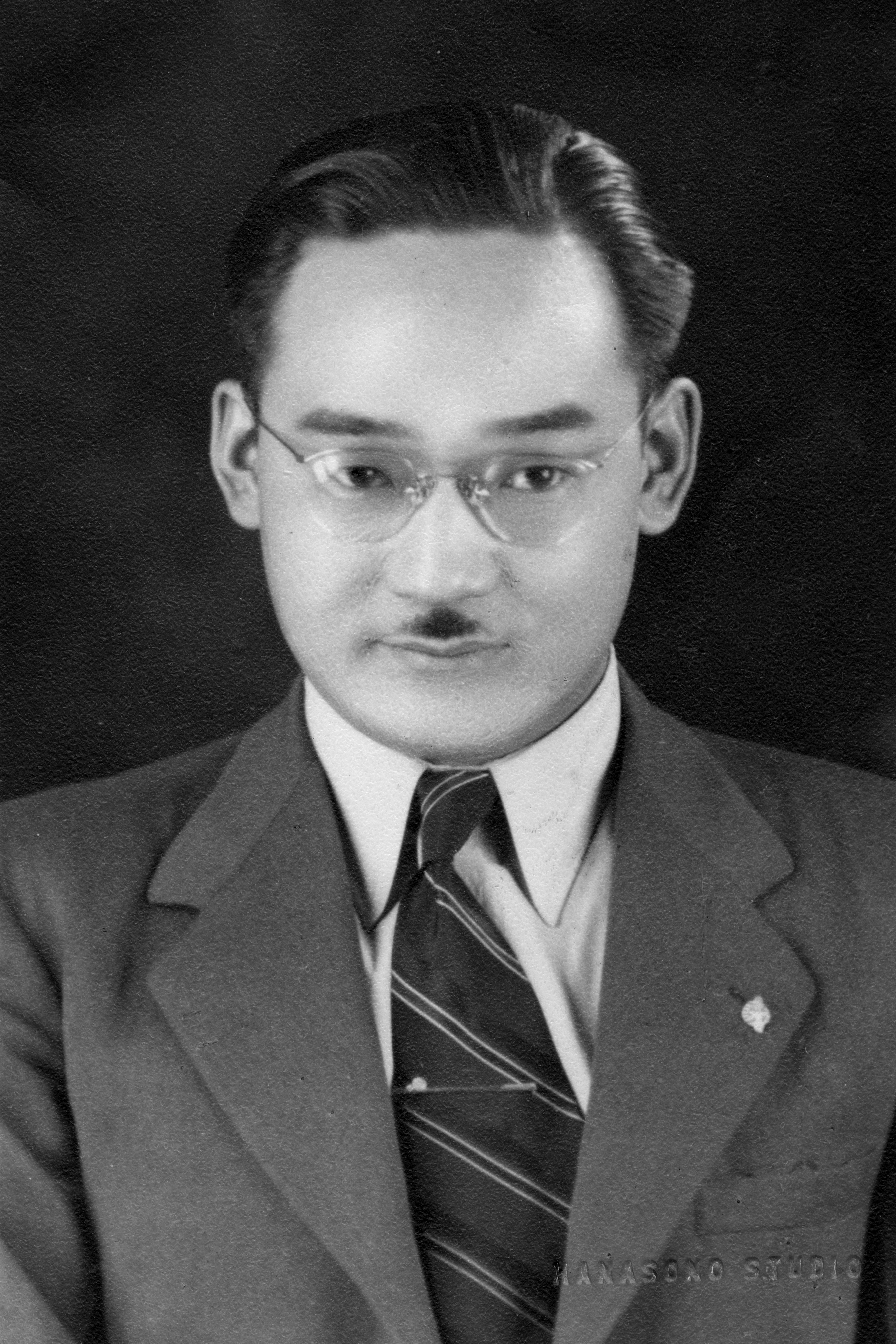

Minoru Yasui.

Courtesy Holly Yasui

-

![Yasui Brothers store, Hood River.]()

Yasui Brothers, store, in Hood River, OrHi 88689.

Yasui Brothers store, Hood River. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Reserach Lib., OrHi 88689

-

![]()

Presidential Medal of Freedom awarded to Yasui.

Courtesy Holly Yasui

Related Entries

-

![Day of Remembrance]()

Day of Remembrance

The Day of Remembrance (DOR) was created as an annual observance of Ex…

-

![Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon]()

Japanese American Wartime Incarceration in Oregon

Masuo Yasui, together with many members of Hood River’s Japanese commun…

-

![Japanese Americans in Oregon]()

Japanese Americans in Oregon

Immigrants from the West Resting in the shade of the Gresham Pioneer C…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ditman, Barbara. “Difficult Choices in Dangerous Times: The Yasui Family in World War II.” Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005),:15-40.

Johnson, Daniel P. “Anti-Japanese Legislation in Oregon, 1917-1923.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 97, no. 2 (1996), 176-210.

Kessler, Lauren. “Spacious Dreams: A Japanese American Family Comes to the Pacific Northwest.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 94, nos. 2-3 (1993): 141-165.

_____. Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family. New York: Random House, 1993.

Minoru Yasui Legacy Project. https://www.minoruyasuilegacy.org/projects.

Takaki, Robert. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Company, 1989.